The medical subspecialty of pediatric rheumatology has grown steadily in recent years amid efforts to shine a light on the field, but a shortage remains critical as more veterans get closer to retirement age.

A scarcity in some parts of the United States means children with rheumatic diseases often travel long distances to be treated for their illnesses.

Access to a pediatric rheumatologist in most states is a challenge and limits the medical options for the more than 300,000 children that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates nationwide are afflicted with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions. Several states have fewer than two board-certified pediatric rheumatologists who treat patients, according to the Arthritis Foundation (AF). Eight states—Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming—have none, says Michael Henrickson, MD, clinical director in the division of rheumatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Board certification for pediatric rheumatology began in 1992 and, some two decades later, there are between 280 to 300 board-certified pediatric rheumatologists in the United States, based on data from the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), the American Medical Association, and the AF. The majority are based in academic centers and clustered in larger, more populated cities, says Emily von Scheven, MD, professor of pediatrics and division chief of pediatric rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Some split their time between research and clinical practice.

A closer look at the numbers reveals an even starker picture. Do the math when you count board-certified certified pediatric rheumatologists and it becomes clear that not all are practicing clinicians, says Dr. Henrickson, who researches and writes about pediatric rheumatology workforce issues.

“Many of the board-certified pediatric rheumatologists live overseas (and may not be American citizens), are full-time bench research scientists, are employed full time in industry positions with pharma companies, or are retired,” Dr. Henrickson noted in an e-mail.

Populations and Geography

Of the many medical centers in Chicago, three have pediatric rheumatologists, but it is still difficult to get coverage for the whole state of Illinois, says Marisa Klein-Gitelman, MD, head of the rheumatology division at Children’s Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Her medical center recruited more faculty members to improve care and reduce wait time for appointments.

The situation is similar—or in some cases worse—in other states. Texas has a large population and not enough pediatric rheumatologists for children who need treatment, says Dr. Klein-Gitelman, who chairs the ACR Special Committee on Pediatric Rheumatology.

States without dense population centers also suffer from the scarcity. Polly Ferguson, MD, associate professor of pediatrics and department director of pediatric rheumatology at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, practices in a state with roughly 3 million people, almost 23% of whom are under 18 years old, according to U.S. Census statistics. She is one of only a few pediatric rheumatologists in the state.

The American Academy of Pediatrics estimates that roughly one-fourth of children with rheumatic disease live 80 miles or more from the nearest pediatric rheumatologist. Travel to doctor appointments can be a daunting enterprise that encompasses lost school days for the ill child and work days for parents, plus the cost of reliable transportation and child care for siblings. “It’s a hardship on families,” notes Dr. Klein-Gitelman.

The scarcity takes a toll on those subspecialty doctors who are lone soldiers covering a vast geographic territory. Dr. Ferguson now has a pediatric rheumatologist partner at the hospital and clinic where they see patients, but there was a time when she was the only one in her state. She recalls always keeping her cell phone with her during a family vacation in the Arches National Park in Utah.

“I don’t know how many phone calls I got when I was out there and every time [my phone] would go off I would have to climb one of the arches because the reception was so poor,” chuckles Dr. Ferguson.

“If you’re by yourself it…doesn’t stop. It’s a continuous workload…” she says, noting that she held a previous post in Alabama where she worked solo. “No matter how hard you work, you can’t keep up with it. You have to learn to prioritize.”

Dr. Ferguson’s solution was to get creative with available resources. She combined forces with other physicians in her institution with shared interest who were willing to step in and handle more basic calls, like filling prescriptions. To better manage the high demand, she relied on the expertise of nurses to triage patients. “The people around you, when they are good, make it a lot, lot better,” says Dr. Ferguson.

Children without access to pediatric rheumatologists may instead see adult rheumatologists or other related subspecialists, says Dr. von Scheven. The statistics that most experts quote, she says, is that about 50% of children with rheumatic disease receive their care from a pediatric rheumatologist and the other 50% from an adult provider.

When the question of the difference between pediatric and adult rheumatologist comes up in conversation, Dr. Ferguson says she likes to make the point that just as doctors wouldn’t send an elderly patient to a pediatrician, it makes no sense to send a child to a doctor accustomed to treating adults. Aside from the disease itself, there are other treatment issues unique to growth phases of a child.

Further, not all adult rheumatologists feel comfortable treating children, says Helen Emery, MD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington and director of medical student education at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Pediatric rheumatologists are trained to watch out for adolescent behaviors that could sabotage treatment. Teenagers are famous for going through phases of denial and “they just don’t take their medicines,” says Dr. Emery.

Growing Older Pains

An ABP 2006 workforce report found that pediatric rheumatology was the 12th most selected pediatric subspecialty among first-time candidates applying for general pediatrics certification. That’s 2.7% of the 866 applicants that showed a career interest in the subspecialty.

This low level of interest foreshadows fewer medical students in line to boost the ranks of certified pediatric rheumatologists and fill vacancies left by retiring baby boomers bidding farewell to the office workplace. Meanwhile, the average age of the present workforce is just over 50 years old, according to ABP data from 2011. That, however, is a decrease from 2010 data when the average age was 52 years old.

The number of people with rheumatic disorders is expected to climb as the aging population swells, leaving experts to predict a significant shortage of adult rheumatologists over the next 20 years as demand outpaces supply. The projected shortage could be even worse for pediatric rheumatologists because they number far fewer than adult rheumatologists. That translates into higher numbers of children whose rheumatic diseases potentially go undiagnosed.

I have seen the number of states without a board-certified pediatric rheumatologist decrease from a total of 14 to the present eight. That is substantive progress over a 12-year interval.

—Michael Henrickson, MD

Recruitment and Education

How will the field replace the expertise and experience of those retiring pediatric rheumatologists? Experts agree that recruitment and education are crucial. Better-paying specialties and pediatric rheumatology’s low profile pose serious challenges to recruiting new doctors. At medical schools where there are no pediatric rheumatology programs, future doctors are not likely to have the specialty on their radar, notes Dr. von Scheven.

“There’s a big problem with exposure,” she says.

Though rewarding in other ways, rheumatology pays less than other specialties, which may cause doctors searching for a niche to overlook the field—and the pediatric rheumatology subspecialty—in favor of more lucrative propositions. Pediatric rheumatologists, like their adult counterparts, face additional financial hurdles because insurance fails to reimburse them for tasks that are routine to their practice.

“A lot of what we do, such as talking on the phone about lab results and helping patients and parents interpret new symptoms, is nonreimbursable,” says Dr. von Scheven.

One way to raise the subspecialty’s prominence is to expand training opportunities across the country and spread the word of the unmet need for pediatric rheumatologists now and in the future. New efforts have been launched in recent years with some success.

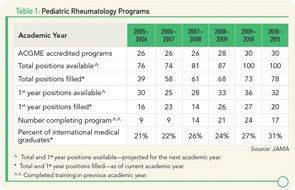

Accredited pediatric rheumatology training programs in the U.S. increased from 26 in 2006 to 30 by 2011, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association (see Table 1). Still, some institutions wanting to add the subspecialty to their programs find it difficult to acquire financing, especially when current fellowship openings go unfilled.

“I anticipate total fellowship training positions would grow if all currently available positions were filled,” says Dr. Henrickson. “Funding fellowship training positions is a challenge for academic institutions. However, there remain fewer applicants than available positions.”

The total number of pediatric rheumatology fellows increased from 74 in 2006 to 93 in 2010 and then dropped to 86 in 2011, according to the ABP, indicating slow and bumpy progress in recruitment. “Those are still teeny, weenie numbers of people graduating and not sufficient to meet the number of people who are retiring,” says Dr. von Scheven.

To get noticed among the competition of other specialties and attract residents with limited exposure to the field, the ACR developed a pediatric residents program to encourage undecided pediatric residents to consider subspecialty training in pediatric rheumatology.

Kids Speak

Sonja Graham’s daughter is 14 years old and sees a pediatric rheumatologist every three months. If her arthritis flares, visits increase to once a month. The Grahams live in Tupelo, Miss., and drive three hours each way to get to appointments. Their state has only one pediatric rheumatologist.

“It puts a huge financial burden on our family,” says Graham. “I have to miss a day of work. Gas money is $100, and if we have to stay at a hotel that’s another hundred.”

Lorrie Pickrell and her daughter Makailya, age 14 years, of Ellsinore, Mo., clock more than three hours each way to get to a pediatric rheumatologist in St. Louis. If Makailya sits too long, her legs and hips hurt.

“We usually stop about halfway for her to get out….It’s an all-day thing,” says Lorrie.

A straight-A student, Makailya dislikes missing school for doctor appointments. She was diagnosed with juvenile arthritis at age seven years, but had complications since she was four years old.

Both families joined the AF’s Advocacy Summit in Washington, D.C., in April to rally congressional support for the Pediatric Subspecialty Loan Repayment Program. The aim is to give more children greater access to pediatric rheumatologists by attracting more medical students to the subspecialty. Congress approved the program as part of the healthcare reform bill, but has not yet appropriated funds for it, says Amy Melnick, vice president of advocacy for the AF.

This is the second year that Makailya attended the AF summit to speak to congressional leaders and meet other children her age with the same disease. She says it is important to tell legislators that more pediatric rheumatologists are needed so that children like her don’t go undiagnosed.

“The day that they finally diagnosed me, I couldn’t walk,” says Makailya. “If they had got me in sooner, I probably wouldn’t be as bad as I am.”

“We contact residency program directors, and anybody who might be interested in pediatric rheumatology has the opportunity to apply for a slot, and there are 25 slots,” says Dr. Klein-Gitelman. “We bring these pediatric residents to the annual meeting. They get to meet fellows and faculty in pediatric rheumatology and have opportunities to interact with them and ask questions, as well as participate in the meeting.”

Every medical problem and every drug you use and every treatment plan you set up has to be considered in light of where the patient is in terms of their growth and development, and that’s constantly changing because it’s such a dynamic process.

—Emily von Scheven, MD

Since it began in 2001, the Pediatric Residents Program has sent 240 residents to ACR annual meetings. Of the participants that completed their residency, 79 applied and were accepted into a pediatric rheumatology fellowship program. The ACR Research and Education Foundation (REF) also funds a visiting professor program that pairs pediatric rheumatologists with academic centers with no pediatric rheumatology training program so they can spend time speaking to medical students, residents and fellows across the country about the subspecialty. The REF also provides funding opportunities for these students to participate in mentored clinical and research experiences within rheumatology. Physicians like Drs. von Scheven and Klein-Gitelman who have participated in the ACR and REF recruitment efforts say they enjoy the holistic aspect of rheumatology and the impact that child development plays in treatment.

“Every medical problem and every drug you use and every treatment plan you set up has to be considered in light of where the patient is in terms of their growth and development, and that’s constantly changing because it’s such a dynamic process,” says Dr. von Scheven.

One of the benefits of being a pediatric rheumatologist is that you are never bored, says Dr. Klein-Gitelman. “Cases are challenging and they require careful thinking,” she says. “No two patients or families are alike, so it is always interesting.”

On the practical side, the field offers scheduling flexibility and growth potential. Middle-of-the-night calls to hospital emergency departments rarely happen. And, given the scarcity, it’s less difficult to find work as a pediatric rheumatologist.

Despite the challenges, there are reasons to be optimistic about the future, says Dr. Henrickson, who, since 1999, has held leadership roles with the ACR and American Academy of Pediatrics.

“During these years, I have seen the number of states without a board-certified pediatric rheumatologist decrease from a total of 14 to the present eight,” says Dr. Henrickson. “That is substantive progress over a 12-year interval.”

Catherine Kolonko is a medical writer based in California.

Alaska’s Outreach Clinic

For several years now, an outreach clinic in Anchorage, Alaska, has offered care to children with rheumatic diseases. The clinic serves as a meeting base where children from nearby communities can be treated on a regular basis by visiting pediatric rheumatologists. It is one way to deal with an undersupply of pediatric rheumatologists across the country, says Helen Emery, MD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington and director of medical student education at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

The busy clinic serves two hospitals in Anchorage, explains Dr. Emery. “We go up there currently four days every other month and split the time between the two,” she says.

The demand is so great that organizers are considering adding two more visits a year to the schedule, says Dr. Emery. Alaska is one of eight states in the country without a certified pediatric rheumatologist.

“Those are very intense clinics….You go from very early in the morning until quite late at night. There’s always more demand than we can get in there,” says Dr. Emery, noting that they are “sort of sandwiching kids whenever.”

A second clinic serves a population over the Cascade Mountains on the borders of Oregon and Washington with pediatric rheumatologists from Seattle. The clinics reduce financial burdens on families who now don’t have to pay for costly airfares and hotels to get to Seattle for treatment. Most medical insurance companies also prefer to have children treated in their hometowns to keep costs down, says Dr. Emery.

Both clinics have operated for six years or more, and demand seems to increase with better awareness of rheumatic diseases, says Dr. Emery. Working in pediatric rheumatology since 1975, Dr. Emery says she has seen great strides in disease management and treatment over the years. The concept of identifying disease early through effective education and aggressive treatment has made a “huge difference to kids with rheumatic disease,” she says.

“We can do so much more for these kids,” says Dr. Emery. “My goal is that, even if you have a rheumatic disease, I want you to look and feel like you don’t have it. That’s a realistic goal these days.”