Patients with late GCA represented 7.4% of all GCA patients in the hospital-based inception cohort. GCA was diagnosed an average of 27 months after PMR or peripheral arthritis. Permanent visual loss developed in 10 patients, including eight of 48 (17%) who developed cranial arteritis. Patients with either form of GCA—usual or late—experienced similar outcomes.

At disease onset, patients with late GCA and controls were indistinguishable, except for a higher proportion of women in the late GCA group. The groups were similar in terms of baseline erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, as well as proportions of patients experiencing long-lasting remission, relapses and resistant PMR or peripheral arthritis.

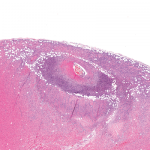

Cranial arteritis was the sole or prominent clinical feature in 48 patients (72%) and was typical (presenting with three or more of the following features: new-onset headache of moderate to severe intensity, jaw claudication or trismus, other jaw/mouth/throat problems, scalp tenderness, and an abnormal temporal artery on physical examination) in 33. Of these 48 patients, eight (17%) developed permanent visual loss (bilateral in three). Twelve patients exhibited transient, visual ischemic symptoms, and four of these developed permanent vision defects. In total, 18 patients (27%) developed visual ischemic symptoms, and all but one exhibited other features of cranial arteritis. Four other patients had extraocular permanent ischemic manifestations. Additionally, subclinical aortitis, headache, and fever were less often associated with late GCA than with the more usual form of GCA.

“Our study demonstrated that late GCA involves a visual ischemic risk that is similar to that of more usual forms of GCA and, therefore, not absorbed by a previous (or current) glucocorticoid treatment for a PMR,” says Dr. Liozon. “As in usual GCA, the risk of permanent visual loss in late GCA is increased in the presence of cranial signs and symptoms, albeit not always prominently, but is much lower in patients featuring systemic symptoms alone or associated with active PMR without cranial features. the implication of this is that any PMR patient (treated or recovered) who recalls persistent cranial symptoms should urgently be explored for a possible late GCA.”

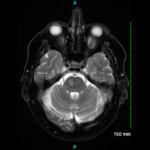

Additional findings showed that of the 20 patients with negative temporal artery biopsy (TAB) (18) or no TAB (2), 12 had large vessel vasculitis evident in positron emission tomography (PET) or computed tomography (CT) scans. Of the 10 patients with previously negative TAB, eight had positive contralateral TAB data at the time of GCA diagnosis. Sixteen patients (24%) had prominent systemic disease mainly diagnosed by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET; of these 16, only one (6%) experienced visual damage.

Implications

“Based on [these] results, patients with isolated PMR do not require more intensive medical care, as long as they do not develop atypical symptoms or signs,” Dr. Liozon says. “rather, our message to rheumatologists is to suggest that they keep in mind that every case of PMR [carries] a risk of developing GCA, notably (but not solely) during the first two years following diagnosis.”