Osteoporosis is a serious, but preventable condition. Hip and vertebral fractures are associated with increased disability, mortality and prolonged care at nursing facilities. In 2005, it was estimated that the cost of osteoporosis-related fractures totaled $17 billion.1

Osteoporosis is more prevalent in aging populations, who often have multiple comorbidities. Patients with impaired renal function are especially challenging because they have a higher incidence of osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD). This includes adynamic bone disease, uremic osteodystrophy, and abnormalities of parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, calcium and phosphorus. Treatment options are limited in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) because bisphosphonates are contraindicated when the creatinine clearance is below 35 mL/min.

Denosumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of osteoporosis in 2010 and is one of the few medications that has been used as a treatment option in patients with CKD.2 Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody with affinity to receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL). It prevents RANKL/RANK interaction, leading to inhibition of osteoclast formation, function and survival.2 We report the development of persistent and symptomatic hypocalcemia in an older patient who was treated with this drug.

We suggest caution when using denosumab in patients with severe renal impairment (GFR <30 mL/min).

Case

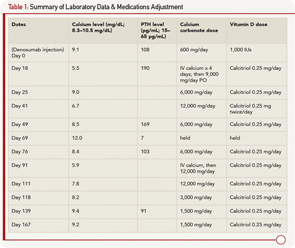

A 79-year-old man with a history of gout, rheumatoid arthritis treated with corticosteroids, type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 CKD due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was evaluated at a rheumatology clinic for increased risk for future fracture based on low T scores of –1.9 at the lumbar spine and –1.7 at the femoral neck. The FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) calculated 10-year risk for hip fracture was 5.5%. His creatinine was 2.7 mg/dL (normal 0.5–1.0 mg/dL) with an estimated GFR of 25 mL/min (normal >60 mL/min), calcium 9.1 mg/dL (normal 8.3–10.5), 25 (OH) vitamin D 25.0 mg/mL (normal 30–100), phosphorus 3.4 mg/dL (normal 2.5–4.8 mg/dL) and PTH 108 pg/mL (normal 15–65). Sixty mg of denosumab via subcutaneous injection was given to the patient as an approved option in patients with CKD. Prior to injection, the patient was taking 600 mg a day of calcium carbonate and 1,000 units/day of vitamin D3.

Two weeks later, the patient developed malaise and upper extremity weakness. Within several days, he was admitted to the hospital with fever of 39.6ºC, malaise, myalgia, tremor, irritability and paresthesias. He was found to have severe hypocalcemia with a calcium level of 5.5 mg/dL, ionized calcium of 0.90 mmol/L (1.13–1.32 mmol/L), PTH 190 and creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. He was evaluated by rheumatology, endocrinology and nephrology, and was diagnosed with hypocalcemia due to denosumab. The patient was treated with IV calcium for four days and subsequently transitioned to oral calcium carbonate 2,250 mg four times a day, and calcitriol 0.25 mg daily. The patient remained in the hospital for eight days due to persistent hypocalcemia. At discharge, his serum calcium was 9.0, creatinine was 2.5 and he was discharged on calcium carbonate 1,500 mg four times a day and calcitriol 0.25 mg daily.

Fifteen days after discharge, his serum calcium was low again, at 6.7, but the patient was asymptomatic. Calcium carbonate was increased to 3,000 mg four times per day, and calcitriol was changed to 0.25 mg twice daily. A week later, his calcium level normalized (8.5 mg/dL), PTH remained elevated (169 pg/mL) and 25 (OH) vitamin D was 21.7. A urine N–telopeptide was 21 BCE/nmol creatinine (normal adult male 9–60 BCE/nmol creatinine). Calcium carbonate was decreased to 1,500 mg four times per day.

Three weeks later, the serum calcium was 12.0, and the PTH was suppressed, at a value of 7 pg/mL. Calcitriol and calcium supplements were held. After another week, the serum calcium level normalized to 8.4 mg/dL with a PTH of 103 pg/mL. Calcitriol was restarted at 0.25 mg/day, with calcium carbonate at 1,500 mg twice daily.

Almost four months after initial injection, the patient became symptomatic and required hospitalization for hypocalcemia (calcium 5.9 mg/dL). He was treated with IV calcium. On Day 6, he was discharged with a normal calcium level and continued on calcium carbonate 3,000 mg/day and calcitriol 0.25 daily. Two weeks later, the serum calcium was 7.8, which required another calcium supplement adjustment. One month later, the serum calcium level increased to 8.2 mg/dL. By the end of the fifth month after injection, the serum calcium had improved. Over the next month, the patient had mild variations in the calcium level and has remained stable since on 750 mg of calcium carbonate twice a day and calcitriol 0.25 mg/day (see Table 1).

Discussion

Our case demonstrates a patient with severe symptomatic persistent hypocalcemia following a single injection of denosumab. Hypocalcemia persisted for nearly six months and required aggressive monitoring and treatment. To our knowledge, this is the longest post-denosumab-related hypocalcemia reported in the literature. During this period, the patient required two hospitalizations, IV calcium and adjustment of the oral calcium/calcitriol dose due to an unstable serum calcium level. Despite the fact that the patient was on calcium and vitamin D supplements and had a normal calcium level before denosumab administration, he developed severe persistent hypocalcemia.

The proposed mechanism for hypocalcemia developing following a denosumab injection is similar to hungry bone syndrome.

A pharmacokinetic study showed that the maximum denosumab concentration (T max) occurred on Day 10 and was independent of renal function.2,3 This correlates with the onset of our patient’s symptoms. Denosumab remains available for up to six months, which may explain the persistent hypocalcemia. The proposed mechanism for hypocalcemia developing following a denosumab injection is similar to hungry bone syndrome.3 Denosumab locks calcium in the bone by inhibiting osteoclasts, but calcium deposition into a new matrix is not affected. Thus, the serum calcium level could fall unless patients have adequate Ca/vitamin D supplementation.

Denosumab had only rare reports of hypocalcemia noted in the FREEDOM trial.4 During the study, only four patients treated with denosumab and five patients in the placebo group had calcium levels less than 8.0 mg/dL. None of these patients were symptomatic. However, another study of 55 patients with various degrees of renal impairment identified 12 patients with hypocalcemia, two of whom required hospitalization.3 It was pointed out that most of these patients were not receiving adequate vitamin D/calcium supplementation.3 All patients with hypocalcemia had some degree of CKD, with more cases of hypocalcemia in patients with severe CKD (three patients) or renal failure (five patients). One additional case of severe symptomatic hypocalcemia in a patient with CKD has been reported.5 Hypocalcemia was reported more frequently in a trial of cancer patients receiving this drug (10.8%) compared with zolendronic acid (5.8%).6

The denosumab label does emphasize a greater risk of hypocalcemia in patients with a creatinine clearance of less than 30 mL/min. It also states that preexisting hypocalcemia must be corrected before denosumab administration and recommends calcium, phosphorus and magnesium level monitoring, as well as adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. However, no clear recommendations regarding monitoring frequency are made.

As demonstrated by our case, aggressive treatment with calcium and vitamin D may be needed.

Although rare, clinically symptomatic hypocalcemia can occur following denosumab injection in patients with decreased renal function. Due to denosumab pharmacokinetics, hypocalcemia may persist for up to six months. As demonstrated by our case, aggressive treatment with calcium and vitamin D may be needed, along with frequent monitoring. We suggest caution when using denosumab in patients with severe renal impairment (GFR <30 mL/min). The serum calcium should be checked routinely 10 days after the injection with adjustments in treatment and monitoring based upon that result.

Lyudmila Kirillova, MD, is originally from Russia, where she earned her medical degree from Ryazan State Medical University. She completed her internal medicine residency at St. Luke’s University Hospital, Bethlehem, Pa., and she subsequently worked as a hospitalist at Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pa., where she is currently a second-year rheumatology fellow.

William Ayoub, MD, is originally from Greensburg, Pa. He graduated from Temple University School of Medicine. He completed his training in Internal Medicine at the Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa. He completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Geisinger in 1983. Dr. Ayoub has practiced clinical rheumatology with the Geisinger Medical Groups in Lewistown and State College since 1983. He serves as the director of rheumatology with the Geisinger Group in State College. He has chaired the Bone Mineral Density Committee and presently chairs the Rheumatology Best Practice Committee within the Geisinger Health System.

References

- Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Washington, D.C. 2013.

- AMGEN. Denosumab prescribing information, package insert.

- Block GA, Bone HG, Fang L, et al. A single-dose study of denosumab in patients with various degree of renal impairment. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Jul;27(7):1471–1479.

- Cummings SB, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Freedom study. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):756–765.

- Talreja DB. Severe hypocalcemia following a single injection of denosumab in a patient with renal impairment. J Drug Assess. 2012 Mar;1:30–33.

- Henry DH, Costa L, Goldwasser F, et al. Randomized, double blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Mar 20;29(9):1125–1132.