Most Americans are willing to subsidize the price of life-saving drugs for patients in poor countries (e.g., AIDS drugs for Africa), but I doubt that many Americans would be so sanguine about underwriting the cost of weight-loss drugs for obese Europeans or antidepressants for the Japanese. Nonetheless, American citizens do subsidize the drug development process by paying disproportionately high prices for drugs. And the subsidy for drug development flows not just to American companies but to European and Asian pharmaceutical companies as well.

Rebalancing the Drug Scales

The American consumers’ (and taxpayers’, too, through the National Institutes of Health) subsidy of the world’s drug development costs clearly contributes to the disparity in spending on healthcare in the United States and is an obvious target for reform. Nonetheless, the high cost of drugs in this country should be corrected not by reform of the healthcare system but by appropriate trade agreements. It is hard to imagine that the industrialized countries will be happy to see the end of the subsidy that Americans provide for their people, but the U.S. economy no longer has the ability to subsidize the world’s consumption of pharmaceuticals.

If the U.S. government were to take up this imbalance and impose a solution that benefitted the American consumer, it should be revenue neutral for the pharmaceutical industry. It would be naive to assume that the pharmaceutical industry would voluntarily lower its prices for American consumers in response to a rebalancing of the cost burden for drugs in the United States. The pharmaceutical industry has rightly been reviled for its pricing and marketing practices in the United States, and is not known for its generosity to the American consumer either. So a change in the way that drugs are priced and purchased in the United States should be the quo for the quid provided by federal trade negotiations.

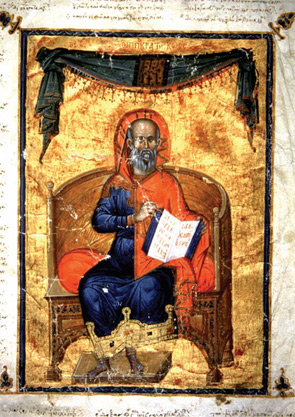

Getting a great price on my mother’s medications was only one of the many pleasures we all shared during our trip to Greece. Indeed, visiting the sites where so much of our culture began deeply impressed my entire family. As a physician, I enjoy knowing that our profession has roots in Greece and that we still take the oath of Hippocrates that originated in this country in the fourth century B.C. Nonetheless, it seems to be a particularly human failing to desire to improve even those things that seem complete already. Indeed, as my mother noted on visiting the Acropolis in Athens, that “they could do so much with this place if they only fixed it up a bit.” Unfortunately, I think that the people of Greece will have the same reaction to my mother’s suggestion as they will to my modest proposal for cutting the cost of medical care in the United States.