de Calancha may have been referring to the wife of the viceroy of Peru, Countess Anna del Chinchon, who miraculously recovered from a febrile illness when given an extract from the bark obtained from native healers. Unknown at the time, the bark contained a number of alkaloids with surprising and enduring pharmacologic properties, including the antimalarial compound, quinine, and the antiarrhythmic, quinidine.

The bark soon made its way to Europe, where, over time, its success in the treatment of ague (i.e., swamp fever or malaria) became well established. In 1742, the physician/taxonomist, Carl Linnaeus, classified the “fever tree” Cinchona officialis, after the legend of Countess Anna del Chinchon.2

In 1820, chemists Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Canentou isolated and purified quinine from Cinchona bark.3 From that time on, a standardized dose and purity for the drug was established. Eventually, the Dutch developed industrial-sized plantations of Cinchona in Java to supply the world antimalarial market.

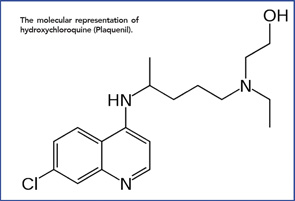

The molecular representation of hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil).

When Japan overran Java in World War II, the world supply of natural quinine shrunk dramatically, just as Allied troops were pouring into the South Pacific. The solution? A synthetic version of quinine, quinacrine (Atabrine), became the drug of choice for the prevention of malaria.4 And the drug worked. As many as 3 million Allied soldiers ingested quinacrine prophylaxis daily for up to three years, with only rare side effects.5

From Malaria to Lupus & RA

Anecdotal reports describing improvement in lupus and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by Allied soldiers on long-term quinacrine culminated in the first published report by Page in the Lancet, in 1951.6 Following this, other papers followed, and the drugs became a mainstay in the treatment of SLE and increasingly prescribed in RA. Over time, other quinine derivatives were introduced by the FDA: chloroquine (Aralen) in 1953 and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil)—differing from chloroquine by a single hydroxyl group side chain, in 1955.

There were missteps. If quinine derivatives were effective in immune-mediated disease, why not combine three antimalarial drugs in a single pill? Triquen (containing 25 mg chloroquine, 50 mg hydroxychloroquine and 65 mg quinacrine) was widely prescribed—until it was withdrawn from the market in 1972 due to frequent retinal toxicity. The chief culprit, chloroquine, became a drug of last resort for refractory SLE rashes. Quinacrine was widely viewed as a safer, but perhaps less effective, drug and eventually could be obtained only through compounding pharmacies (although Edmund Dubois, MD, and later, Daniel J. Wallace, MD, at UCLA, continued to prescribe it regularly for their lupus patients).7