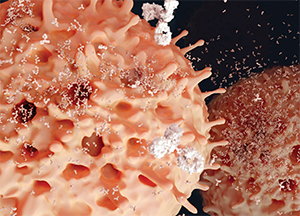

Plasma cells segregating antibodies.

Juan Gaertner/shutterstock.com

The findings were presented at the Annual Congress of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2016 by researchers at Leiden University Medical Center and Groene Hart Hospital, both in The Netherlands. They were part of a session highlighting the growing interest in the role that plasma cells can play in the tenacity of RA, acting as a kind of disease engine that finds safe harbors in the body and can be difficult to combat.

The work from the researchers in The Netherlands was an attempt to dig deeper into the understanding of ACPA antibodies, a marquee feature of RA. Research shows these antibodies seem to be actively involved in instigating or worsening or perpetuating the disease, or even all three.

“Despite all this knowledge, we actually know very little about the cells that make these antibodies,” said Hans Ulrich Scherer, MD, PhD, a researcher at Leiden. “Knowledge about these cells might be very relevant.”

The Research

To study how cells from the synovial compartment affect the longevity of B cell responses that produce ACPA, researchers collected mononuclear cells from synovial fluid and from peripheral blood in patients with established RA. They used the ELISPOT assay to detect cells that were spontaneously secreting ACPA-immunoglobulin G (IgG). Then the mononuclear cells from both sources were cultured, using no additional stimuli, to assess the degree of spontaneous ACPA-IgG secretion.

The results were striking. The synovial fluid mononuclear cells showed up to a 200-fold increase of ACPA-IgG secretion compared to that in peripheral blood, even though the number of B cells was lower in the synovial fluid.

Researchers found that a median of 12%—but up to 50%—of all IgG-secreting cells in synovial fluid were ACPA-IgG-secreting.

Plus, this spontaneous ACPA-IgG secretion was, as they put it, “remarkably stable” in the synovial fluid cultures, detectable for several months, as opposed to only a few weeks in peripheral blood, they found.

“We consistently saw this prolonged period of ACPA-IgG production in the synovial fluid culture, where in the PBC [peripheral blood cultures], this died out rather rapidly,” Dr. Scherer said.

‘The synovial compartment is equipped to function as an inflammatory survival niche for plasma cells. And it could indicate the sustained ACPA production facilitated by this environment could contribute to the chronicity of synovial inflammation in RA.’ —Dr. Scherer

He said the results indicate the synovial compartment is a microenvironment that promotes the survival of these ACPA-IgG secretions.

“This indicates that the synovial compartment is equipped to function as an inflammatory survival niche for plasma cells,” Dr. Scherer said. “And it could indicate the sustained ACPA production facilitated by this environment could contribute to the chronicity of synovial inflammation in RA.”

He said researchers are only “at the very beginning” of understanding exactly how the synovial fluid provides such a great environment for these plasma cells to produce ACPA-secreting cells.

Researchers looked for factors that could promote the survival of these plasma cells for so long, but haven’t identified anything specific yet. But that has been hampered, perhaps, by the complex culture that’s involved, making it difficult to identify the cells or survival factors of interest.

“We did not see a specific signal coming up,” he said. “That could also have to do with the fact that it’s a very mixed culture in which we don’t know how many of the cells that are still in there are actually the ACPA-IgG-producing” cells.

Autoreactive Memory Plasma Cells

In another talk, Andreas Radbruch, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Charité University in Berlin, said autoreactive memory plasma cells—which essentially give inflammation a memory, making it difficult to extinguish—present “a therapeutic challenge.” They can be generated in the preclinical stage of RA and continuously after that.

The levels of autoantibodies maintained despite immunosuppressive therapy are an indication of the memory plasma cells that are secreting them.

“They are refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy, such as glucocorticoids, anti-TNF or anti-CD20 antibodies, aiming at the termination of ongoing immune reactions,” he said. “Memory plasma cells secreting pathogenic antibodies thus can provide the memory of chronic inflammation.”

The memory cells don’t live long by themselves, but are aided by survival factors, such as anti-Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 and a proliferation-inducing ligand.

“Understanding the lifestyle of memory plasma cells has provided strategic options to target them, but so far almost all therapeutic options do not discriminate between pathogenic and protective plasma cells, and thus imply loss of humoral memory and increased risk of infections,” Dr. Radbruch said. “The therapeutic challenge is to ablate pathogenic plasma cells selectively and maintain protective humoral memory as much as possible, and to prevent regeneration of memory plasma cells from their precursors.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.