A hug is a handshake from the heart.

—Author Unknown

After many years as a nurse in an intensive care unit, I started working as a nurse practitioner in a busy rheumatology practice in 2000. From my background in retail management and the intensive care unit, I had been taught that a handshake was part of the proper introduction to a new patient. (See Figure 1, p. 37.)

What I didn’t expect from greeting rheumatology patients with a handshake, though, were the furrowed brows, looks of concern, and hesitant hands coming at me when I did offer my hand. I quickly learned that patients were resistant to shake hands out of fear that their hand would be hurt by this common salutation. Since then, I stopped shaking patients’ hands—until I received a particular office memo.

The Office Memo

Two years after my realization about problems in greeting rheumatology patients, our practice manager sent a memo that included an article relating increased patient satisfaction with their physician to a handshake made upon entering the room. The handshake conveyed the message that the healthcare provider was interested in meeting the individual’s emotional and physical needs.

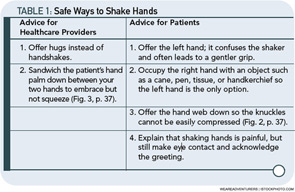

Clearly, not everyone saw pain in patients’ faces when they shook their hands. I shared my dilemma of wanting to make physical contact upon entering the room but not wanting to hurt my patients with the practice manager. We discussed potential solutions, but clearly the topic needed further research.

More Study

For six months, I read every article I could find about hand pain and researched acceptable greetings across different cultures. Two that were particularly helpful were “Dr. Shiel’s patented handshake for arthritis patients” and Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands.1,2 After this review, I asked patients what they did to avoid shaking hands. I was shocked to find that a simple handshake affected patients’ lives so adversely.

Some patients admitted that they avoided Sunday church services so they wouldn’t be in situations where a meeting might involve a handshake. Many patients acknowledged that they routinely apologized for not wanting to shake hands; worse, many admitted that they endured the pain, sometimes for days, a handshake would bring.

Additionally, I researched public figures like retired Senator Robert Dole (R-Kan.) and his tactics to shield his right hand, which had been extensively damaged by a war injury. Senator Dole is said to deliberately keep his right arm bent so his injured arm is not subjected to the handshake. He holds a trademark pen to prevent people from grabbing his hand for a handshake. Senator Dole also pivots his body clockwise, preemptively, a quarter-turn toward an approaching person. His strategies have helped maintain a posture of political strength despite not conforming to the traditionally accepted politician’s handshake.

A Historical Perspective

Most historians agree that the handshake originated in England years ago to allow strangers to acknowledge that an individual was unarmed. The original custom was to shake the left hand because most weapons were concealed in the left sleeve of the shirt to allow quick access to one’s weapon. After the custom evolved, most individuals were unarmed and began to shake with the right hand.