A hug is a handshake from the heart.

—Author Unknown

After many years as a nurse in an intensive care unit, I started working as a nurse practitioner in a busy rheumatology practice in 2000. From my background in retail management and the intensive care unit, I had been taught that a handshake was part of the proper introduction to a new patient. (See Figure 1, p. 37.)

What I didn’t expect from greeting rheumatology patients with a handshake, though, were the furrowed brows, looks of concern, and hesitant hands coming at me when I did offer my hand. I quickly learned that patients were resistant to shake hands out of fear that their hand would be hurt by this common salutation. Since then, I stopped shaking patients’ hands—until I received a particular office memo.

The Office Memo

Two years after my realization about problems in greeting rheumatology patients, our practice manager sent a memo that included an article relating increased patient satisfaction with their physician to a handshake made upon entering the room. The handshake conveyed the message that the healthcare provider was interested in meeting the individual’s emotional and physical needs.

Clearly, not everyone saw pain in patients’ faces when they shook their hands. I shared my dilemma of wanting to make physical contact upon entering the room but not wanting to hurt my patients with the practice manager. We discussed potential solutions, but clearly the topic needed further research.

More Study

For six months, I read every article I could find about hand pain and researched acceptable greetings across different cultures. Two that were particularly helpful were “Dr. Shiel’s patented handshake for arthritis patients” and Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands.1,2 After this review, I asked patients what they did to avoid shaking hands. I was shocked to find that a simple handshake affected patients’ lives so adversely.

Some patients admitted that they avoided Sunday church services so they wouldn’t be in situations where a meeting might involve a handshake. Many patients acknowledged that they routinely apologized for not wanting to shake hands; worse, many admitted that they endured the pain, sometimes for days, a handshake would bring.

Additionally, I researched public figures like retired Senator Robert Dole (R-Kan.) and his tactics to shield his right hand, which had been extensively damaged by a war injury. Senator Dole is said to deliberately keep his right arm bent so his injured arm is not subjected to the handshake. He holds a trademark pen to prevent people from grabbing his hand for a handshake. Senator Dole also pivots his body clockwise, preemptively, a quarter-turn toward an approaching person. His strategies have helped maintain a posture of political strength despite not conforming to the traditionally accepted politician’s handshake.

A Historical Perspective

Most historians agree that the handshake originated in England years ago to allow strangers to acknowledge that an individual was unarmed. The original custom was to shake the left hand because most weapons were concealed in the left sleeve of the shirt to allow quick access to one’s weapon. After the custom evolved, most individuals were unarmed and began to shake with the right hand.

My husband teaches sales classes at Michigan State University in East Lansing. During an etiquette dinner, students are encouraged to shake hands firmly to convey confidence and positive nonverbal cues to members that they call on in the industry. It was apparent to me that this common greeting must be challenged to prevent pain to a patient and the need to apologize for avoiding a handshake or a “polite” greeting.

A Case Study and a Lecture

The case of Robert illustrates the handshake dilemma. A businessman and a former college athlete, Robert is in great physical condition. At 45 years old, Robert stands 6’3” and weighs 250 pounds. Robert lives with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and he knows all too well how painful a handshake can be. His arthritis has been controlled for two years on biologic and disease-modifying therapy. He continues to play pick-up hockey.

As I explained the topic to Robert, he agreed that it would help many people. He also offered his solution: “I just offer my left hand.” Confused, I asked what he meant. “I just offer my left hand, and that way people don’t squeeze it as hard,” he explained. Even Robert, a physically imposing person and athlete, was making adjustments to his greeting.

It was then that I realized that this problem didn’t limit itself to those with physical deformities to their hands, but to all who have chronic pain which affects their hands. Patients with scleroderma, fibromyalgia, RA, osteoarthritis, erosive osteoarthritis, gout, psoriatic arthritis, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and polymyositis are just some of the patients affected with hand pain. My passion for this subject turned into a lecture for the Michigan’s Focus on Pain Conference in 2008, and the reception confirmed the widespread nature of this problem.

Solutions

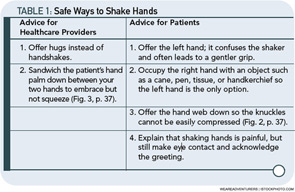

Physical touch conveys empathy, shows connection, and raises the self-esteem of those who are touched. Based on experience, research, and patients, there are several ways to shake hands (see Table 1, below left).

Over the years, I found two solutions that work well for my patients and me. Most patients get a hug upon entering the room and before they leave the office. For patients with whom I am less familiar, or who are less receptive to physical touch, an open palm gentle touch to the forearm, shoulder, or knee and crouching to the patient’s eye level conveys that I care and plan to give them compassionate care without shaking their hand. In addition to touch, I always take the time to talk to our patients for at least two minutes before turning to the computer to review the electronic medical records.

In an era of electronic medical records and reliance on lab tests, scans, and evidence-based medicine, the importance of a full physical exam that is comprehensive but does not worsen the patient’s pain is imperative. My exams are thorough, but I save the most uncomfortable part of the examination for last and frequently ask during the exam if my touch is painful. To help myself and others in our office, I derived an acronym for the best way to treat patients with chronic painful condition without exacerbation of their pain.

L Learn the patient’s personal history.

E Encourage positive life behaviors.

A Acknowledge the importance of touch.

R Reduce the victimization mentality.

N Never give up trying to improve the quality of a patient’s life.

Some patients have picked up on my “hug” therapy. Recently, one patient informed the front desk checkout secretary that I had forgotten something. The secretary interrupted my next patient to tell me that my previous patient said I had forgotten to give her something. I got to the front desk and my patient said, “I didn’t get my exit hug.”

Apparently, hug therapy is working.

Treating patients with chronic pain can provide a challenge in any setting. Even patients with no overt physical deformity can be hurt with a gesture as simple as a handshake. The medical community must set a precedent by educating the public that a firm handshake is not the only way to convey strength, wholeness, and competence in business. Other greetings need to be embraced and explored based on individual level of comfort and familiarity. Patients deserve compassion and personalized attention; physical touch conveys this. We must all just think before we squeeze.

Iris Zink is a nurse practitioner at the Beals Institute in Lansing, Mich.

References

- Shiel WC, Jr. Dr. Shiel’s patented handshake for arthritis patients. www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=20192. Reviewed June 6, 2004. Accessed July 7, 2010.

- Morrison T, Conaway WA. Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands, 2nd ed. Adams Media: Avon, Mass.;2006.