Originally posted Feb. 13, 2023; reposted in conjunction with publication of the PMR supplement to the February 2024 issue of The Rheumatologist.

PHILADELPHIA—Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a chronic inflammatory condition that almost exclusively affects individuals older than 50.1 First described in 1888, PMR has been a recognized rheumatic disease since at least 1957. Diagnosing the condition can be challenging.2 Diagnosis is usually made after recognition of the classic clinical features and the patient’s adequate response to a trial of glucocorticoids (i.e., 12.5–25 mg prednisone equivalent), but atypical presentations or inadequate responses to glucocorticoids occur. Additionally, no therapies for PMR are approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), and many patients experience frequent relapses and prolonged courses of glucocorticoids.

Exciting presentations at ACR Convergence 2022 by Claire E. Owen, PhD, FRACP, and Christian Dejaco, MD, challenged the existing paradigm of PMR stasis, suggesting more use of imaging modalities and the possible introduction of interleukin (IL) 6 inhibitors in light of recent successful trials.

Imaging

Dr. Owen is an early career clinician-researcher and deputy director of rheumatology at Austin Health, Malvern East, Victoria, Australia. Her doctoral thesis characterized the demographic, clinical, laboratory and imaging phenotype of PMR patients with a relapsing disease course. Results of this work informed a proof-of-concept positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (PET/MRI) fusion study confirming peritendinitis as a pathologic hallmark of PMR and provided the basis for the development of a novel scoring algorithm for diagnosing PMR on whole body PET/computed tomography (CT).

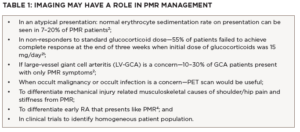

Providers rarely order imaging to diagnose PMR, but Dr. Owen argued that ultrasound, MRI and PET/CT scans may have a role in better characterizing and diagnosing PMR.3-11 In particular, she highlighted situations in which imaging may be especially useful, including atypical presentations, non-responders to initial therapy, and differentiating classic mimickers of PMR, such as rotator cuff tendinitis and rheumatoid arthritis (see Table 1).

Choosing the correct modality can be challenging, and only ultrasound findings are currently included in the most recent ACR/EULAR classification criteria for PMR, which were published in 2012.1 Generally, ultrasound is more readily available than MRI or PET/CT at centers with expertise, but it typically evaluates fewer structures and is highly operator dependent.

All three modalities can help differentiate PMR from mechanical musculoskeletal etiologies because any study with two or more areas of disparate involvement would suggest PMR. Peritendinous inflammation—even in the absence of an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) and an inadequate response to standard initial treatment with glucocorticoids (i.e., 12.5 mg–25 mg per day of prednisone)—may also suggest PMR. MRI findings can be especially helpful in defining the location of synovitis with extracapsular synovitis favoring a diagnosis of PMR and intracapsular synovitis favoring rheumatoid arthritis (see Table 2).

However, clinicians using imaging for PMR management must be aware of important limitations. Especially among patients with a high pretest probability of disease, the cost/benefit of using expensive tests like MRI or PET/CT may be prohibitive. Ultrasound may be more affordable, but evaluations are operator dependent and require advanced training in musculoskeletal ultrasound. The role of any modality outside of diagnosis has yet to be defined. Finally, whenever novel diagnostic modalities are introduced, the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment increases.

How would you treat a patient with no symptoms of giant cell arteritis (GCA), but who has signs of large vessel inflammation on a vascular ultrasound of the axillary arteries? The automatic response would be to increase glucocorticoids and consider initiating therapy with tocilizumab, but the clinical outcomes of such subclinical GCA patients have yet to be defined. It seems plausible that increasing immunosuppression in such patients, who may have done well with a standard PMR glucocorticoid taper, would increase therapy-related complications without commensurate benefits.

Despite these unanswered questions, imaging has a vital role in PMR in cases of uncertain diagnosis, especially when clinical concern for large vessel GCA or occult malignancy or infection exists.

Immunosuppression Risks & Benefits

The second half of the ACR 2022 Convergence presentation was given by Dr. Dejaco and addressed the risks and benefits of further immunosuppression with glucocorticoid-sparing agents in patients with PMR.

Dr. Dejaco is the head of the Department of Rheumatology, South Tyrol Health Trust, Azienda Sanitaria Alto Adige, Brunico, Bolzano, Italy, and an associate professor at the Medical University of Graz, Austria. His main field of interest is in imaging and vasculitis.

Many patients with PMR receive high cumulative doses of glucocorticoids, with over half remaining on glucocorticoids two years after diagnosis and approximately 25% remaining on glucocorticoids after five years.12 Prolonged glucocorticoid use in patients with PMR, even at low doses, has been associated with significant morbidity.13-15

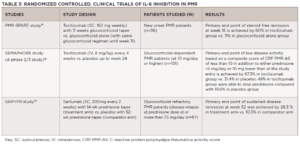

The 2015 EULAR/ACR recommendations for the management of PMR suggest methotrexate as a glucocorticoidsparing agent, but studies of its utility have been mixed.15,16 Recent publications, including on the PMR-SPARE trial, SEMAPHORE and, most recently, the SAPHYR study, which was presented in a plenary session at ACR Convergence 2022 (see Table 3), have suggested a role for IL-6 inhibition in PMR.18-20

It is important to highlight differences in inclusion criteria: SAPHYR and SEMAPHORE studied IL-6 inhibition in relapsing or glucocorticoid-dependent patients; PMR-SPARE evaluated patients with new-onset disease. All three studies identified benefits with glucocorticoid sparing and preventing flares, which is a highly encouraging result and merits further investigation.

Despite these exciting data, important questions about who should receive these therapies remain. Patients with up-front risk factors for glucocorticoid toxicities, such as diabetes, osteoporosis or cardiovascular disease, would be a reasonable group. However, many would argue that almost all patients over the age of 50 are at risk of glucocorticoid-related complications, and the largest risk factor—eventual cumulative glucocorticoid exposure—is currently not one we can reliably predict. Even among patients who ultimately require prolonged courses of glucocorticoids, it is not clear when patients should start IL-6 inhibition or how to balance the risks of low doses of glucocorticoids against the initiation of a biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD).

Should IL-6 inhibitors be initiated up front, or should this be saved for relapsing/glucocorticoid-dependent patients? What dose of glucocorticoid dependence would warrant the use of IL-6 inhibitors? For example, for a patient taking 3 mg/day of prednisone whose disease is in clinical remission is there any advantage to using IL-6 inhibitors? We currently are unable to say with any certainty, although most rheumatologists would favor extending and slowly tapering 3 mg/day of prednisone.

Based on the SAPHYR study, the FDA has now approved sarilumab for PMR; however, which patients should receive it will be an important question to answer in coming years.

In Sum

Caveats notwithstanding, it has been exciting to see recent advances in imaging and treatment options for patients with PMR. Imaging modalities may provide important information for diagnosis and prognosis, while IL-6 inhibitors may offer hope for patients with relapsing and refractory disease. Acknowledging that patients with PMR are primarily cared for in the primary care setting is important, and dissemination of these advances in diagnosis and treatment to primary care providers is needed for patients to have timely rheumatology assessments.

It seems clear that the next decade of research and therapeutics for PMR will be full of excitement and innovation.

*Since the original publication of this article, sarilumab has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of PMR.

Desh Nepal, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Sebastian E. Sattui, MD, MS, is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and the director of the UPMC Vasculitis Center. His research focuses on the treatment of systemic vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica, and the intersection of inflammatory conditions and aging.

Michael Putman, MD, MS, is an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, where he is the medical director of the Vasculitis Program and maintains an active practice in general rheumatology. He is involved in education and currently serves as the associate program director for rheumatology, associate program director for internal medicine, and medical school co-director for hematology and immunology. His research interests include clinical trials in vasculitis, big data epidemiology and meta-research. He is also an associate editor of the journal Rheumatology and hosts the Evidence-Based Rheumatology podcast.

Disclosures

Sebastian E. Sattui has received research funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline (clinical trials), and participated in consulting and advisory boards for Sanofi and Amgen (funds toward research support).

References

- Dasgupta B, Cimmino MA, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. 2012 Provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Apr;71(4):484–492.

- González-Gay MA, Matteson EL, Castaneda S. Polymyalgia rheumatica. Lancet. 2017 Oct 7;390(10103):1700–1712.

- Koski JM. Ultrasonographic evidence of synovitis in axial joints in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. Br J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar;31(3):201–203.

- McGonagle D, Pease C, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. Comparison of extracapsular changes by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. J Rheumatol. 2001 Aug;28(8):1837–1841.

- Fruth M, Buehring B, Baraliakos X, Braun J. Use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis to describe changes at different anatomic sites which are potentially specific for polymyalgia rheumatica. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018 Sep–Oct;36 Suppl 114(5):86–95.

- Fruth M, Seggewiss A, Kozik J, et al. Diagnostic capability of contrast-enhanced pelvic girdle magnetic resonance imaging in polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Oct 1;59(10):2864–2871.

- Laporte JP, Garrigues F, Huwart A, et al. Localized myofascial inflammation revealed by magnetic resonance imaging in recentonset polymyalgia rheumatica and effect of tocilizumab therapy. J Rheumatol. 2019 Dec;46(12):1619–1626.

- Van der Geest KSM, van Sleen Y, Nienhuis P, et al. Comparison and validation of FDG-PET/CT scores for polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 Mar 2;61(3):1072–1082.

- Blockmans D, De Ceuninck L, Vanderschueren S, et al. Repetitive 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in isolated polymyalgia rheumatica: A prospective study in 35 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Apr; 46(4):672–677.

- Yamashita H, Kubota K, Takahashi Y, et al. Whole-body fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with active polymyalgia rheumatica: Evidence for distinctive bursitis and large-vessel vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2012 Sep;22(5):705–711.

- Cimmino MA, Camellino D, Paparo F, et al. High frequency of capsular knee involvement in polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis patients studied by positron emission tomography. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 Oct;52(10):1865–1872.

- Floris A, Piga M, Chessa E, et al. Long-term glucocorticoid treatment and high relapse rate remain unresolved issues in the real-life management of polymyalgia rheumatica: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Jan;41(1):19–31.

- Wu J, Keeley A, Mallen C, et al. Incidence of infections associated with oral glucocorticoid dose in people diagnosed with polymyalgia rheumatica or giant cell arteritis: A cohort study in England. CMAJ. 2019 Jun 24;191(25):E680–E688.

- George MD, Baker JF, Winthrop K, et al. Risk for serious infection with low-dose glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):870–878.

- Pujades-Rodriguez M, Morgan AW, Cubbon RM, et al. Dose-dependent oral glucocorticoid cardiovascular risks in people with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020 Dec 3;17(12):e1003432.

- Dejaco C, Singh YP, Perel P, et al. 2015 recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Oct;67(10):2569–2580.

- Dejaco C, Singh YP, Perel P, et al. Current evidence for therapeutic interventions and prognostic factors in polymyalgia rheumatica: A systematic literature review informing the 2015 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Oct;74(10):1808–1817.

- Bonelli M, Radner H, Kerschbaumer A, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with new onset polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR-SPARE): A phase 2/3 randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Jun;81(6):838–844.

- Devauchelle-Pensec V, Carvajal-Alegria G, Dernis E, et al. Effect of tocilizumab on disease activity in patients with active polymyalgia rheumatica receiving glucocorticoid therapy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022 Sep 20;328(11):1053–1062.

- Spiera R, Unizony S, Warrington K, et al. Sarilumab in patients with relapsing polymyalgia rheumatica: A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial (SAPHYR). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(suppl 9).

- Hutchings A, Hollywood J, Lamping DL, et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and diagnostic uncertainty in the first year of polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Jun 15;57(5):803–809.