The Inflection Point

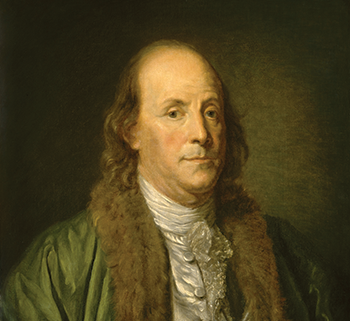

Benjamin Franklin

Everett – Art / shutterstock.com

In medicine, as in life, it is often too early to act, until it is suddenly—irrevocably—too late. In clinical therapeutics, the trick is to catch patients at the inflection point, the moment at which the patient’s health is transitioning from good to bad. Finding that inflection point, that’s the trick.

We all know the penalties of waiting too long. Years ago, I was confronted by a patient of mine who had a long-time diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis. She had come into my clinic after years of falling in and out of the medical system, with the gaps patched by too much prednisone. I straightened out her regimen, tapered her prednisone and dutifully recorded that she was in remission. When I told her this, she became angry. How could she be in remission? She still became winded when she walked up a flight of steps, she still had trouble bending forward to pick up the mail off her stoop. When would the medications start to work?

I realized then that we had been talking past each other for months. I turned away from the computer to face her, and I told her as gently as I could that for me, remission just meant her disease was no longer creating new problems. The medications did not reverse the damage caused by her diagnosis when the disease was active or the damage caused by the drugs that had been used over the years to manage her disease. For these, we were dependent on her body’s natural healing processes, but the healing did not occur spontaneously. It would require time and hard work on her part to return to the level of function that she craved.

I never saw her again.

Benjamin Franklin, Rheumatologist?

Founding Father of the United States Benjamin Franklin, was many things. He was a politician, diplomat, humorist, scientist and inventor. Sometimes, I wonder if he was also a rheumatologist.

In 1733, Mr. Franklin faced the problem of fires in his adopted city of Philadelphia. At the time, when a building was on fire, good doers would show up and try to help. And just like when a code blue is called over the hospital intercom, the people who show up might be a motley crew of varying skills and interests, leaving the fate of the burgeoning Philadelphia cityscape in the hands of happenstance.

Unable to persuade the City of Brotherly Love that it needed a more organized way of responding to threats to the burgeoning cityscape, he wrote an anonymous letter to his own newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette. “In the first Place, as an Ounce of Prevention is worth a Pound of Cure, I would advise ’em to take care how they suffer living Coals in a full Shovel … when your Stairs being in Flames, you may be forced (as I once was) to leap out of your Windows, and hazard your Necks to avoid being oven-roasted.”2

Rheumatologists also know that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. No amount of etanercept will heal the deformities of a burnt out rheumatoid arthritis; no amount of cyclophosphamide will heal the kidneys of a patient with microscopic polyangiitis on dialysis. We, therefore, start patients with mild disease on mild drugs, hoping to prevent the severe complications that await.