One of my fellows could take better care of his patients if it weren’t for the attendings getting in his way. Or so he tells me.

I can hear the howls of protest already. This statement isn’t fair—it is too broad, it doesn’t fairly depict the nuances of the situation or his point of view. First, I should point out that I know for a fact the trainee in question does not read this column, so I think I am safe, as long as none of you tell on me.

Should he find out, I would quote Erma Bombeck. If you are of a certain age, you may recall Ms. Bombeck was a nationally syndicated writer and humorist, whose columns were read by millions. She was also a wife and mother, who often wrote about her own life experiences. As you might imagine, as her children aged, they found this less amusing. One day, her children held an intervention: They informed her that if she was going to write about them, then she should be more even-handed in her depiction of them. To this, Ms. Bombeck responded with the same motherly affection and tenderness I would pass on to my own trainee, should he raise any objections: “Go out, and get your own column.”1

Honestly, the dispute comes down to a single patient, and I don’t know all the details. As a program director, I often hear bits and pieces about what irritates the fellows about various faculty members (including—more often than I like to admit—me). As in any family, however, not all arguments were meant to be voiced, and over the years, I have decided I should function less in loco parentis and more in loco avunculus—I try to lend a sympathetic ear, give some free advice when I can and slip them a $20 when Dad is being especially tough.

This particular patient is a young woman who has centromere-positive, limited scleroderma, whose care the fellow had inherited. The fellow noted, astutely, that she had a little interstitial lung disease, and over the past year, had developed a little more.

The fellow fought to start treatment, in this case, with mycophenolate mofetil, imagining that a few pills now would save her from needing a lung transplant later. His attending demurred, arguing the lung disease was still asymptomatic, and watchful waiting was all that was needed at this time.

I certainly understand the impulse to treat—I often joke with colleagues that if I wanted to just watch sick patients become sicker, I would have become a neurologist. I am glad some physicians are attracted to this important work, but I find the management of diseases like stroke and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to be incredibly depressing. I became an internist because I want to be able to make people better.

A true product of my training, for any patient’s complaint, I can come up with a pill. This is probably one reason why my clinic visits run long; I just can’t resist giving a patient a Medrol dose pack for his slipped disc or a steroid cream for his nummular eczema. From the legions of discharged patients who walk out with a prescription of docusate clutched in their hands, I know many of you feel the same way.

The Inflection Point

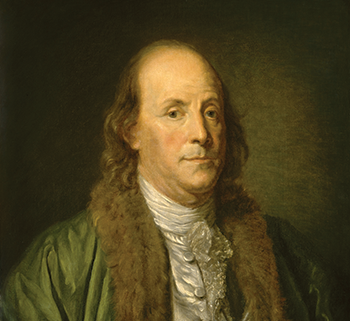

Benjamin Franklin

Everett – Art / shutterstock.com

In medicine, as in life, it is often too early to act, until it is suddenly—irrevocably—too late. In clinical therapeutics, the trick is to catch patients at the inflection point, the moment at which the patient’s health is transitioning from good to bad. Finding that inflection point, that’s the trick.

We all know the penalties of waiting too long. Years ago, I was confronted by a patient of mine who had a long-time diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis. She had come into my clinic after years of falling in and out of the medical system, with the gaps patched by too much prednisone. I straightened out her regimen, tapered her prednisone and dutifully recorded that she was in remission. When I told her this, she became angry. How could she be in remission? She still became winded when she walked up a flight of steps, she still had trouble bending forward to pick up the mail off her stoop. When would the medications start to work?

I realized then that we had been talking past each other for months. I turned away from the computer to face her, and I told her as gently as I could that for me, remission just meant her disease was no longer creating new problems. The medications did not reverse the damage caused by her diagnosis when the disease was active or the damage caused by the drugs that had been used over the years to manage her disease. For these, we were dependent on her body’s natural healing processes, but the healing did not occur spontaneously. It would require time and hard work on her part to return to the level of function that she craved.

I never saw her again.

Benjamin Franklin, Rheumatologist?

Founding Father of the United States Benjamin Franklin, was many things. He was a politician, diplomat, humorist, scientist and inventor. Sometimes, I wonder if he was also a rheumatologist.

In 1733, Mr. Franklin faced the problem of fires in his adopted city of Philadelphia. At the time, when a building was on fire, good doers would show up and try to help. And just like when a code blue is called over the hospital intercom, the people who show up might be a motley crew of varying skills and interests, leaving the fate of the burgeoning Philadelphia cityscape in the hands of happenstance.

Unable to persuade the City of Brotherly Love that it needed a more organized way of responding to threats to the burgeoning cityscape, he wrote an anonymous letter to his own newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette. “In the first Place, as an Ounce of Prevention is worth a Pound of Cure, I would advise ’em to take care how they suffer living Coals in a full Shovel … when your Stairs being in Flames, you may be forced (as I once was) to leap out of your Windows, and hazard your Necks to avoid being oven-roasted.”2

Rheumatologists also know that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. No amount of etanercept will heal the deformities of a burnt out rheumatoid arthritis; no amount of cyclophosphamide will heal the kidneys of a patient with microscopic polyangiitis on dialysis. We, therefore, start patients with mild disease on mild drugs, hoping to prevent the severe complications that await.

Very Early Rheumatoid Arthritis as the Model

The therapeutic march backward, toward the point of disease inception, is well exemplified by the history of rheumatoid arthritis therapeutics. The 1958 revision of the American Rheumatism Association criteria was focused on identifying the epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis, by dividing patients into four categories: classic, definite, probable and possible.3 Realizing that patients with classic rheumatoid arthritis also likely had developed a substantial amount of irreversible disease, the race was on to identify patients at earlier stages of development. The 2010 ACR/EULAR rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria are now old-hat: the push now is to identify patients with so-called “very early rheumatoid arthritis” to treat.

In medicine, as in life, it is often too early to act, until it is suddenly—irrevocably—too late. In clinical therapeutics, the trick is to catch patients at the inflection point, the moment at which the patient’s health is transitioning from good to bad.

The ERA (Early Rheumatoid Arthritis) trial defined early rheumatoid arthritis as disease that was present for less than three years.4 The AVERT (Assessing Very Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment) trial defined very early rheumatoid arthritis as disease that was present for less than two years.5 Long-term follow-up from the ERA trial demonstrates that early use of biologic therapies can decrease the cumulative amount of damage suffered by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The AVERT trial indicates that even earlier use of biologics may cause some patients to enter a sustained, drug-free remission.

That’s the dream. Every drug, no matter how benign, has side effects. The idea that using a biologic now for a limited period of time may prevent a patient from needing to take a shot or a pill for the next several decades is extraordinary.

Perhaps we have been dreaming too small. The Prevention of Clinically Manifest Rheumatoid Arthritis by B-Cell Directed Therapy in the Earliest Phase of the Disease (PRAIRI) study looked at whether we could prevent patients from developing rheumatoid arthritis in the first place.6 This study took 89 patients to clinics in the Netherlands with arthralgias (but not arthritis), and randomized them to receive either 1 gram of intravenous rituximab or placebo. All patients also received 100 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone.

The overall risk of developing clinical arthritis after a median of 29 months of follow-up was 40%. Treatment with a single dose of rituximab reduced the risk of developing arthritis at 12 months by 55%. Unfortunately, the effect was not permanent: The patients in the placebo group developed arthritis after a median time of 11.5 months. The patients who received rituximab developed arthritis after a median period of 16.5 months.

From a conceptual standpoint, this is intriguing: It is fascinating to think a single dose of rituximab may hold off the cascade of events that leads to a clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, even if only for a little bit of time. Longer term, if the investigators could demonstrate the single dose of rituximab leads to some long-term benefit, such as less aggressive disease or fewer erosions, we might be even more intrigued.

From a practical aspect, just think of all the patients that you see in your clinic with arthralgias. Now imagine going through the pre-approval paperwork to get each of those patients their single dose of rituximab. The mind reels.

The trick, of course, will be to learn how to distinguish the progressers from the non-progressers. If 40% of patients developed arthritis, then it stands to reason that 60% did not. Although it is possible those patients may have, eventually, developed arthritis as well, it seems equally possible they would have done just as well if left completely alone.

Actually, that group would have done even better. According to the Cochrane group, the number needed to harm for rituximab, when used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, is seven.7 This means only seven patients need to receive rituximab for one of them to suffer as a result. When I can see the disease in front of me, this is a number I can live with. When the risk is theoretical and statistical, however, I may lose my nerve.

First, Do No Harm

I have been a practicing rheumatologist long enough to know that I have deliberately harmed my patients. Hemorrhagic cystitis from cyclophosphamide, cytokine storm from rituximab, hypersensitivity pneumonitis from infliximab. I have also borne witness to the sins of those who came before me, particularly in the form of secondary malignancies that arose as the result of therapies started before I was a rheumatologist. The fact that these side effects are rare is cold comfort to the patient who falls in the tail of the bell-shaped curve.

When I am treating a patient with life-threatening, systemic vasculitis, I still sleep easy at night knowing the risk of a rare side effect is better than losing their kidney function, for example. When the potential for benefit is small, however, the calculus becomes more complicated.

The Scleroderma Lung Study I demonstrated that a year of treatment with oral cyclophosphamide led to a 2.5% improvement in forced vital capacity, when compared with placebo.8 The long-term follow-up from this study indicates this benefit is no longer detectable a year after the cyclophosphamide has been stopped.9 The Scleroderma Lung Study II indicates that mycophenolate is as good as cyclophosphamide, but when you look at the numbers, it seems to be damning with faint praise.10

One could try to invoke the rheumatoid arthritis model and argue we should be treating patients earlier, when their disease is more malleable. That said, the therapeutics of rheumatoid arthritis are much more appealing; if biologics led to only a 2.5% improvement in the ACR20 score, I doubt we would be spending much time discussing the treatment of very early rheumatoid arthritis.

For rheumatoid arthritis, the potential of treating preclinical rheumatoid arthritis seems promising. For other diseases, it is difficult to be certain. Some patients with other preclinical rheumatic diseases probably could benefit from being treated much earlier, but before we are ready to move in that direction, much work remains to be done.

As for my fellow, when he has my job and I’m playing shuffleboard in Boca, I wonder what he will tell his fellow to do with a patient in the same scenario. I would guess that whatever he says, he will be a lot less certain saying it. As Yogi Berra once said, “It’s tough to make predictions. Especially about the future.” Come to think of it, maybe Yogi Berra was a rheumatologist, too.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, is an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, is an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program.

References

- Bombeck B. Life with Erma a roller-coaster ride. Tucson Citizen. 1996 May 10.

- Union Fire Company.

- Ropes MW, Bennett GA, Cobb S, et al. 1958 revision of diagnostic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1959 Feb;2(1):16–21.

- Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 30;343(22):1586–1593.

- Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the phase 3b, multicenter, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, within a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jan;74(1):19–26.

- Gerlag DM, Safy M, Maijer KI, et al. Effects of B-cell directed therapy on the preclinical stage of rheumatoid arthritis: The PRAIRI study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Dec 1;0: 1–7.

- Lopez-Olivio MA, Urruela MA, McGahan L, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 20;1: CD007356.

- Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. New Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 22;354(25):2655–2666.

- Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Effects of 1-year treatment with cyclophosphamide on outcomes at 2 years in scleroderma lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov 15;176(10):1026–1034.

- Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): A randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016 Sep;4(9):708–719.