“Prior authorization is the single most detrimental factor to patient therapy because it can delay treatment initiation and/or continuity of care, which in turn may negatively impact patient outcomes,” says Georgia Bonney, CMPM, CRMS, CRHC, practice manager for Virginia Rheumatology Clinic, Chesapeake. “In a system where we are striving to reduce disease activity and payers want us to focus on quality metrics to prove our worth, the prior authorization process can feel like a detour to failure.”

Ms. Bonney

Prior authorization is part of a broader set of cost control measures (e.g., step therapy, forced switching, restrictive formularies, specialty tiers, and substitution of biosimilars or generic drugs) implemented by payers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or other agents engaged to manage healthcare benefits, says Christopher Phillips, MD, a rheumatologist in solo practice in Paducah, Ky., and chair of the Insurance Subcommittee to the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. The rationale is to prevent wasteful healthcare spending, but in reality prior authorization often serves as a delaying tactic, making patients and doctors jump through hoops before needed drugs are approved.

Dr. Phillips

“We’ve been subjected to prior authorization for years, but it has become increasingly more burdensome,” says Dr. Phillips.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, some insurers suspended prior authorization requirements. But now it’s back to business as usual, and with increasing access to nonemergent medical care, insurers are raising new obstacles to try to limit their financial exposure.

“In the field of rheumatology, it’s possibly even more burdensome than for other medical specialties,” says Dr. Phillips. “Not surprisingly, all of our newer, more expensive drugs need prior authorization. But in our office, we’ve seen that even generic NSAIDs [non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs], methotrexate or prednisone might require a prior authorization.”

Dr. Phillips’ practice, like many others, employs the equivalent of a full-time staff person dedicated just to working through prior authorization and similar reviews for prescribed drugs. Most often, these drugs eventually get approved, but that can take weeks or, occasionally, months. “Three months later,” he says, “we see the patient again, assuming they’ve been taking the medication we ordered all that time, and find out they weren’t getting it.”

Impact on Practices

In a 2018 AMA survey of 1,000 physicians, three-quarters of respondents reported that prior authorization hassles can lead to patients abandoning treatments and 91% said it has delayed their patients’ access to care.1 They also reported their prior authorization burden had increased over the previous five years.

A single-center study of prior authorization in rheumatology found that 71% of 225 patients required prior authorization to begin infused medications—despite the fact that 96% of the prescriptions were ultimately approved.2 Even those patients eventually approved for treatment had a higher burden of steroid use because of delays in approval of prescribed medications.

Dr. Feldman

“There is no uniformity in the list of drugs requiring prior authorization among and within various health plans,” says Madelaine Feldman, MD, FACR, president of the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO) and a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group, New Orleans. “That confirms there is little science behind these requirements, particularly when we see generic steroids requiring prior authorization. It is purely a delaying tactic that results in harm to the patient and an unnecessary burden to the physician’s office.”

Ms. Ruffing

Rheumatology nurse Victoria Ruffing, RN-BC, director of nursing and patient education for the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center and adjunct faculty at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, says variations in the prior authorization process create delays for practices and patients. Not all medications require prior approval. It’s complicated and variable, she says.

Ms. Zlatkus

“Some payers include quantity limits in the prior authorization based on a patient’s current weight instead of a prior authorization for mg/kg,” says Andrea Zlatkus, CMPM, CRMS, CRHC, executive director of the National Organization of Rheumatology Management, Wilmington, N.C. “Therefore, if you have an authorization for a specific number of vials and the patient has a weight adjustment, you may not be able to change the dose because it requires an updated authorization. This is something many nurses struggle with because it goes against their training.”

Every year, a PBM may rework its formulary—with new financial incentives for preferred drugs. A medication previously denied may now be preferred, Ms. Ruffing says. “So we have to rework our medical plan for the patient. Or the patient gets switched under their employer’s health benefits to a new insurance company.”

There’s always a deluge of recertifications required in January, when many patients switch insurance companies. And prior authorization approvals that were granted for a year or two can be overturned when circumstances change, requiring a new round of recertification.

In the case of denial, the provider must start the appeal process. Not all insurers issue denials for the same reasons. “The insurance company may say, ‘Drug B must have failed to improve the patient’s condition before we will consider the prescribed drug,’ ” says Ms. Ruffing. “However, approval for Drug B isn’t guaranteed. It’s not uncommon to receive a second denial, stating, ‘Before you try Drug B, you have to try Drugs C and D, and they have to prove ineffective, too.’ ”

Ms. Manning

Laura Manning, RN, nurse coordinator for the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center, relates a common patient scenario. “Let’s say the doctor orders the biologic monoclonal antibody Cosentyx [secukinumab] for psoriatic arthritis on day 1. On day 2, the pharmacy does a benefit scan and finds the prior authorization requirement. At Johns Hopkins we work with our internal pharmacy, which has helped streamline the authorization process. Still, it can take several days to find out the prescription has been denied and a letter from the clinician is required to overturn the denial.”

“When an insurer asks if the medication was ordered by a rheumatologist, it would be nice if that were deemed sufficient,” Ms. Ruffing says.

According to Ms. Manning, preparing each appeal letter can take 30 minutes, plus another 15 to 20 minutes negotiating the insurer’s website to file it.

QUICK TIP

Keep a spreadsheet for each payer your practice deals with. Include the payer’s:

- Website URL;

- Telephone/fax number for the prior authorization department;

- Telephone/fax number for the appeal department; and

- Any specific details, such as time limits for the authorization and appeals processes.

Appeals can take two weeks or more to adjudicate. In one case, a secukinumab denial was overturned after 32 days. “We had started the patient on a manufacturer-supplied free sample of the medication, but in the meantime, we found it really wasn’t working for this patient. So the doctor ordered a new medication, and that was denied. That appeal took another 28 days. And when the doctor ordered another new medication, the payer said they wanted us to try Cosentyx.”

Manufacturer samples or bridge programs aren’t always available, but if the patient is in bad shape and needs medication immediately, they can help. “But we shouldn’t have to rely on samples or bridge programs,” says Ms. Manning.

Unfortunately, bridge programs are prohibited by government insurance plans, including Medicare.

“The administrative burden, staff time commitments and response turnaround time required by prior authorization can be lessened by process improvements,” says Ms. Bonney. “So my first rule of prior authorization denial prevention is to have a reliable and thorough prior authorization process in place.” (See sidebar for tips and best practices.)

Reform Needed

The ACR has made reducing the burdens of prior authorization one of its top advocacy priorities. It issued a position statement on March 18, 2020, addressing prior authorization and the burdens it creates, and offering a number of recommendations for streamlining the process. Recommendations include reducing the number of rheumatology specialists who would be subject to prior authorization requirements, so long as they adhere to evidence-based practice and meet defined performance measures, and reducing through regular reviews the number of services or medications that require prior authorization.

In January 2018, a number of medical groups, including the ACR and the American Medical Association (AMA), issued a consensus statement on principles to guide the reform of utilization management, such as by more selective application.

The ACR has joined with 13 other national medical specialty groups in the Regulatory Relief Coalition to endorse H.R. 3173, the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021, reintroduced in Congress in May by Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-Wash.) and others. The bill would reform and streamline requirements for prior authorization for Medicare Advantage plans, making it speedier and more transparent, and establish a national electronic prior authorization system that insurers would be required to adopt. Medicare Advantage is viewed as a place to start building a coalition of advocates to tackle other insurance sectors as well.

State legislatures are another important target for advocacy against the disruptions caused by prior authorization and similar measures. In March this year, Nebraska passed a law restricting step therapy, joining two dozen other states that have already done so.

Dr. Feldman recommends the CSRO map tool to see the status of legislation, active or enacted, in each state regarding various utilization management tools, including step therapy, non-medical switching, prior authorization and PBM transparency.

Let the Physician & Patient Decide

“Our position is that we should let the patient and provider decide what’s the best treatment for them—period,” says Dr. Phillips. “There are any number of idiosyncrasies to individual cases that could shape the doctor’s judgment on the right answer for a particular patient.”

The ACR offers practice management resources to help members deal with prior authorization and other insurance related issues. Send an email to [email protected], or visit http://www.ACRInsuranceAdvocacy.org.

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION: 20 BEST PRACTICES

If practice managers have a mantra, it’s document, document, document:

- Document in the medical record what medications have been tried and failed, with dates. If this can be carried forward in subsequent notes, it saves a lot of time for the person preparing the prior authorization request or letter of appeal. It also helps to know why a medication failed to help the patient (e.g., increased liver enzymes, development of a new rash).

- Know your state’s prior authorization laws.

- Have a process for prior approvals, and review it regularly. The process may look different in every practice and will depend on practice size, number of physicians, staff, etc. Having a process gives staff a plan of action for documentation and follow-up. Regular review of the process allows for changing payer protocols and staff changes, and can keep things as lean and proficient as possible.

- Designate a person to oversee the prior authorization process. This person will provide oversight for submissions, turnaround times for staff and payers, policy changes, etc.

- Be sure the process is known to all staff. How is an authorization request initiated? Who gets the assignment? Is there an office policy for when the initial submission by staff must be accomplished (e.g., within 24–48 hours of the prescription being issued)? Does your practice have a follow-up policy? What happens if the authorization is denied? If it’s approved, who receives the approval and what do they do with it? How is the patient notified and in what time frame?

- Know the requirements of your top payers, their top formulary products and the fastest way to submit requests. Does the payer prefer to receive prior authorization requests via eFax, paper fax, phone call or other method? What is the process to request nonpreferred drugs or a clinical review?

- Track and follow up on prior authorization requests. Maintain a master list that all staff can reference to obtain the status of a request.

- Keep the patient in the loop. Make sure the patient is aware of your prior authorization process and keep them updated with information about coverage and denials, copay programs and out-of-pocket costs.

- Document and record in your patient’s chart the authorization details including:

- File a copy of the approval letter with the reference number, date and time, and identity of the person who issued the authorization;

- Date range for the approval;

- Amount approved within the timeframe, such as Drug X—300 mg every six weeks.

- Understand the process to extend or obtain a new authorization. Most payers allow you to renew 30 days out.

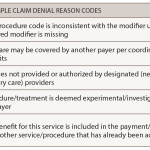

When a denial is received:

- Review the practice process policy to make sure denials are not inadvertently being created due to a process disconnect.

- Review the denial: What is the reason given? Does it make sense?

- Review the prior authorization submission to ensure the correct information was provided.

- Does the medical record documentation support the request?

- If the denial is for clinical reasons or due to a try-and-fail policy, provide that information to the rheumatologist or prescriber. Would they like to proceed with an appeal or change to a preferred product (give them the product options)?

“If authorization is denied, appeal,” says Ms. Zlatkus. “Most appeals are approved.” If the decision is made to appeal the denial:

- Clarify how the payer prefers to receive an appeal.

- Include measurement details in an appeal letter. Example: “The patient’s Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) is 24, representing high disease activity.”

- Include any issues with activities of daily living. Be specific.

- If you have pictures of the patient’s condition (e.g., swollen joint[s], psoriasis, rash), include them in the appeal. Pictures go a long way.

- Embed in the body of the letter any literature review that helps bolster your position for going outside the tier system or for off-label uses. “We have used package inserts for FDA approval definition, white papers, peer reviewed articles, etc.,” says Ms. Bonney, “but our best success has always been having our physician conduct a phone discussion with the medical and/ or pharmacy director within the plan. These calls typically last less than five minutes and have an overwhelmingly positive outcome for the patient.”

“I have let the insurance companies know I am cc’ing the state attorney’s office and the state’s insurance commissioner,” says Ms. Ruffing. “Make note of the addresses for the offices in your state.”

Larry Beresford is a medical journalist in Oakland, Calif.

References

1. 2018 American Medical Association. Prior authorization (PA) physician survey.

2. Wallace ZS, Harkness T, Fu X, et al. Treatment delays associated with prior authorization for infusible medications: A cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov;72(11):1543–1549.