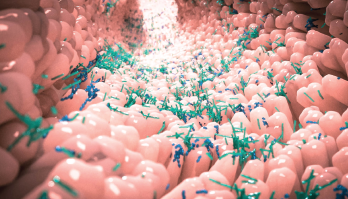

Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics / shutterstock.com

Researchers know human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules affect susceptibility to disease in general, and immunological disease in particular. In the case of ankylosing spondylitis (AS), the risk is primarily associated with HLA-B27, with smaller effects from other HLA alleles. Current thinking is that AS is caused by the presence of a genetically primed host because the condition is highly heritable.

Some patients have identified food as a trigger for flairs, and certain diets appear to be beneficial. Some patients have even gone so far as to suggest these beneficial diets may change the prevalence of certain bacteria.

That said, previous studies have yielded mixed results regarding the importance of microbiome diversity in symptoms of AS and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). To complicate matters, researchers have noted marked gender biases in RA and AS, as well as evidence in mice that gender-related hormonal differences are associated with differences in the intestinal microbiome.

Nevertheless, some patients modify their diets and experiment with prebiotics and probiotics. They may try colonic lavage and fecal transplant therapy. Although these approaches can shift the microbiome and prove beneficial in some conditions (although currently no evidence supports a benefit in AS or RA), often the microbiome reverts, and symptoms reappear.

New Studies Shed New Light

Now, new research suggests that although genes may prime the host, the gut microbiome may be the trigger. The data also provide more evidence the genes that cause AS and RA may do so through the microbiome. Specifically, changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiome commonly seen in patients with AS and RA appear to be at least partially due to the effects of HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1 on the gut microbiome.

The research by Mark Asquith, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Ore., and colleagues is consistent with the hypothesis that HLA alleles cause or increase the risk of these diseases via interaction with the intestinal microbiome.1 The results, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, also suggest therapies targeting the microbiome may help prevent and/or treat AS and RA.

“In this study, we have demonstrated for the first time that in the absence of disease or treatment, HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1 have significant effects on the gut microbiome in humans,” write the authors. “This is consistent with HLA-DRB1-associated observations in mice and the effect of HLA-DRB1 alleles upon Prevotella copri abundance in humans. This extends previous demonstrations that AS and RA are characterized by intestinal dysbiosis by confirming that this is, at least in part, due to the effects of the major genetic risk factors for AS and RA, [which include the] HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1 risk alleles, respectively.”

This finding is consistent with other disease models in which HLA molecules interact with the gut microbiome to cause disease.

Research has previously demonstrated the gut microbiome in patients with AS and, to some extent RA, differs from findings in healthy patients, but it remained unclear from these studies if the differences helped cause the disease or were due to the disease or its treatment. To help distinguish these possibilities, Asquith and colleagues looked to see if the genes that cause AS or RA influenced the gut microbiome in healthy individuals not on arthritis treatments.

They first performed 16S rRNA profiling and small nucleotide polymorphism array genotyping on 107 healthy individuals (with 564 biopsy samples). The investigators found a clear distinction in the microbiome profile between luminal stool samples and mucosal samples, as well as between the mucosal samples from different intestinal sites. They found this difference was largely driven by differences in the ileal samples from the colonic mucosal samples, which largely clustered together. They also found a significant association between body mass index and microbiome composition. After analyzing this data, the researchers focused their attention on stool samples, which are much more convenient to obtain than ileal or colonic mucosal samples.

When the investigators controlled for body mass index and gender, they found a significant association between HLA-B27 genotype and HLA-DRB1 alleles and overall microbial composition. In other words, even in the absence of disease, the major genes involved in AS and RA influenced the gut microbiome. The influence of the host’s genetics appeared to affect primarily the overall composition of the microbiome as opposed to the overall species diversity. HLA-B27-positive subjects had reduced carriage of Bacteroides ovatus, Blautia obeum and Dorea formicigenerans across multiple sites.

In the case of AS, it appears bacteria physically migrate across the host cell wall and drive the inflammatory processes of disease. This suggests pathophysiology is not merely a matter of the immunological responses of the gut, but rather the result of systemic cytokine response to gut bacteria.

“It is unlikely microbiome-based treatments will cure disease,” says Matt Brown, MBBS, MD, director of genomics at the Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, and corresponding study author. Once any treatment targeting the gut microbiome stops, the patient’s genetically primed immune system likely reshapes the microbiome again, back to what it was prior to treatment.

Dr. Brown explains their research didn’t point toward microbial load being a significant factor in disease. Instead, it seemed to be a matter of microbial diversity. This finding is consistent with studies in inflammatory bowel disease that found patients with inflammatory bowel disease had decreased microbial diversity.

That said, vedolizumab, an anti-integrin-α4β7 monoclonal antibody approved as a treatment for both moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, is associated with an increased risk for AS, which “suggests microbiome interaction in those two diseases is quite different,” says Dr. Brown.

When pressed to discuss the clinical implications of his work, Dr. Brown says very few proper clinical trials relate changes in the gut microbiome to clinical outcomes for AS and RA, and this research remains in the early stages. “We don’t really know what bugs are healthy and what bugs drive disease,” he says.

Inflammatory bowel disease may be simpler than AS and RA, according to Dr. Brown, because the latter two diseases require complex interactions between the microbiome and the systemic immune system, rather than just affecting primarily the gut wall. “It is reasonable for rheumatologists to be cautious about microbiome-

targeted therapies,” he says.

Dr. Brown also authored a paper (submitted for publication and available on BioRxiv.org) that reinforces the key role the gut microbiome plays in driving the pathogenesis of AS.2 In this study, investigators found tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors shifted the microbiome, leading the authors to wonder if one of the beneficial effects of TNF inhibitors is this shift. If true, a question yet to be resolved is whether the bacteria themselves are the key contributors to pathology, or whether it is something the bacteria produce (or don’t produce).

The gut microbiome produces multiple short-chain fatty acids, such as propionic acid, butyrate and acetate. Although it remains unclear which of these (or another one altogether) is missing or created in excess by the microbiome, if such an imbalance were a problem, it should be possible to address it via supplementation with short-chain fatty acids or by shifting the microbiome to increase the production of certain short-chain fatty acids. Either or both approaches may ultimately benefit patients with AS and/or RA.

The new data support further research into manipulation of the microbiome to either treat established disease, or prevent disease in at-risk patients.