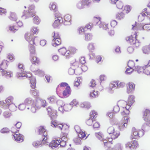

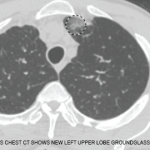

Although eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis can affect many organ systems, it most commonly damages the lungs. Many patients present with asthma symptoms and, occasionally, pulmonary infiltrates. Additionally, patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a predominance of eosinophils in their peripheral blood and tissues. This finding has led researchers to suggest that eosinophils play an important role in disease pathogenesis.

Although eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis can affect many organ systems, it most commonly damages the lungs. Many patients present with asthma symptoms and, occasionally, pulmonary infiltrates. Additionally, patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a predominance of eosinophils in their peripheral blood and tissues. This finding has led researchers to suggest that eosinophils play an important role in disease pathogenesis.

Recently, Michael E. Wechsler, MD, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues reported that patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis who are treated with the anti-interleukin 5 monoclonal antibody, mepolizumab, experience significantly more weeks of remission than patients receiving placebo. The investigators published the results of their randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in the May 18 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.1

The study included 136 patients with the rare condition of relapsing or refractory eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. All of the patients were receiving standard-of-care therapy, which meant the population was representative of patients with the disease who are treated with glucocorticoids (at least 7.5 mg prednisone per day) with or without additional immunosuppressive therapy. The clinical trial enrolled patients at centers of expertise that were equipped to document glucocorticoid use throughout the trial. The study also had two primary endpoints: accrued weeks of disease remission and the proportion of patients who were in remission at Weeks 36 and 48. The investigators used the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) to characterize disease activity and outcomes.

“The results of our trial show an advance for patients with this rare disease,” write the authors in their paper. “Approximately half the participants with relapsing or refractory eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis who were treated with mepolizumab had clinically relevant improvements in the rates of protocol-defined remission and relapse, which allowed for reduced glucocorticoid use. Although 81% of the participants in the placebo group had no accrued weeks of remission, 47% of those in the mepolizumab group did not have protocol-defined remission, either, which suggests that not all patients will have the same benefit.”

In other words, 28% of patients in the treatment group experienced ≥24 weeks of accrued remission, whereas only 3% of patients in the control group experienced ≥24 weeks of accrued remission. In addition, at both Weeks 36 and 48, many more patients in the treatment group than placebo group were in remission (32% vs. 3% at both weeks). The study did not reveal any new safety signals from mepolizumab.