Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is now a prominently recognized disease, but its arrival on the world stage has been a recent occurrence (see timeline at the bottom of page 18). Archeologists have unearthed evidence that PsA existed as early as the fifth century, but the disease was not recognized as a discrete entity until 1963. The landmark papers of John M. Moll, BSc, DM, and Verna Wright, MD, outlined the unforgettable diversity of phenotypes (dutifully memorized by every rheumatology fellow) and family associations, although it was not until 2006 that validated diagnostic criteria were reported. Scientific studies centered on the pathobiology of this disorder were not published until the 1980s, and clinical studies also were small and, in general, open label, prior to the advent of the biologics in the late 1990s. Fortunately, interest in PsA has been accompanied by a quantum leap in knowledge about the clinical and scientific aspects of this disease (see Table 2, p. 19). We also have witnessed unparalleled advances in therapy.

PsA Emerges as a Distinct Entity

Although the coexistence of psoriasis and arthritis had been noted for many years, it was not until the early 1940s that physicians began to question the nature of the association in detail. Walter Bauer, MD, a past president of the American Rheumatism Association, wrote a typically erudite paper that was presented to the American Association of Physicians, in which he highlighted several of the features we now recognize as typical of PsA.1 Dr. Wright entered this arena in 1955 when he arrived in Leeds, United Kingdom. At that time, “junior” doctors (fellows) who aspired to be academics were encouraged to spend time in the United States. Dr. Wright secured a position with Richard Johns, MD, at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and his remit was the biomechanics of joints. Before he departed for the United States, however, he approached the senior nurse at the Royal Bath Hospital in Harrogate, a spa town located in peaceful, verdant surroundings conducive to recovery from the ravages of rheumatism. Patients often stayed at the spa for several weeks undergoing treatment. Dr. Wright asked the nurse to jot down the names of all patients admitted to the hospital who also had psoriasis. On his return, he systematically analyzed this assembled cohort, and the results formed the basis of his 1959 paper, “Rheumatism and psoriasis: A re-evaluation.”2

In separate but parallel studies, the unique features of this distinct arthropathy were also described by H. Baker, MB, a dermatologist from London, who published his findings somewhat later.3 The data revealed in these manuscripts combined with the recognition that the sheep cell agglutination test (rheumatoid factor) was often negative in patients with arthritis and psoriasis were the key factors that influenced the American Rheumatism Association to formally recognize this arthropathy as distinct from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 1964.4

Dr. Wright realized that a number of inflammatory joint disorders shared clinical features common to PsA: the absence of rheumatoid factor, a predilection for lower-limb oligoarthritis, spinal involvement with sacroiliitis, eye inflammation, and skin disorders resembling psoriasis. He persuaded a succession of bright young doctors to join him in his quest, and these pioneers set about describing the clinical associations that linked inflammatory bowel disease, ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, Behçet’s disease (then believed to be a member of this group), and PsA. His group also recognized the familial clustering of these diseases (before the discovery of HLA-B27), and they collected a number of impressive family pedigrees.5,6 The culmination of this work, frenetically carried out in a period in the late 1960s and early 1970s, culminated in the monograph Seronegative Polyarthritis, which outlined the evidence for this distinct group of disorders.7 Dr. Wright was extremely proud of this book, co-authored and illustrated by his collaborator, Dr. Moll.

TABLE 1: Historical and Clinical Landmarks in Psoriatic Arthritis

1850–Jean Louis Alibert’s monograph on association between psoriasis and arthritis published

1941–Dr. Bauer presents paper to American Rheumatism Association (ARA) on the association between psoriasis and “rheumatoid arthritis” (RA)

1956–First publication by Dr. Wright on PsA27

1964–ARA recognizes PsA as separate from RA

1973–Landmark paper by Drs. Moll and Wright describes the five subgroups5

1978–Dr. Gladman establishes first cohort of patients in Toronto

1991–Original five subgroups of Drs. Moll and Wright challenged

1998–Dr. McGonagle paper published in Lancet9

2000–First paper describing beneficial effect of anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs in psoriatic arthritis

2003–First meeting of GRAPPA

2006–Publication of classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis (CASPAR)10

2007–Publication of outcomes measures in PsA11

2008–Publication of PsA treatment guidelines12

Following the frenetic efforts of the 1970s, the early 1980s was a relatively quiet period. Dr. Wright had many other interests. He had established a department of world renown, not only in spondyloarthropathy but also in pharmacology, forging early links with large pharmaceutical companies in rehabilitation and bioengineering. His reputation naturally led to a stream of overseas visitors and fellows from diverse disciplines. One fellow from Italy, Antonio Marchesoni, MD, was assigned to review the records in the psoriatic arthritis “register” and to perform a retrospective analysis of cases over the prior 10 to 20 years. The register consisted of a card index file but, sadly, after such a long period, many of the patients had moved on or, in some cases, died. Nevertheless, enough information was available to perform an imaging study that widened the subgroup classification of PsA.8

Advances in PsA in the Post-Wright Era

Shortly after this study, Dr. Wright died and with him, many of his A4 notebooks (famous the world over). Fortunately, when the department finally cleared out of Clarendon Road in Leeds, many of his original research worksheets (what we would now call CRFs) were found, some eaten by mice and some damp, but others well preserved. On review of these worksheets, it was possible to glimpse the painstaking methods carried out in medical research from the 1950s—all the notes were handwritten, recorded neatly in columns, and annotated with comments and asides on clinical features. If that was not enough, all the statistics were calculated manually and noted in meticulous handwriting!

Leeds has continued its reputation as a leading center for research in PsA, and the infirmary has expanded on Dr. Wright’s legacy. In the 1990s, a young Irish physician journeyed to Leeds, and some years later his Dublin mentor commented, “Always had a big brain, that boy.” Dennis McGonagle, PhD, perceptively and convincingly revitalized the fundamental paradigms in these disorders. He partnered with Mike Benjamin, PhD, MD, an anatomist from Cardiff, and they have performed seminal studies on the enthesis and its central role in the pathogenesis of spondylitis.9

Shortly afterwards, Will Taylor, PhD, a visiting fellow from New Zealand, was instrumental in assembling the first international collaboration to develop new classification criteria for PsA.10 This latter initiative led to the formation of a more permanent group of investigators with strong interests in the science and clinical aspects of PsA. The impetus for this effort was provided by Philip Mease, MD, of Seattle Rheumatology Associates, and Dafna Gladman, MD, in Toronto Western Hospital in Ontario, Canada. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) currently has more than 300 members worldwide, and this organization has pioneered a number of important initiatives related to outcome assessment and treatment recommendations, and has improved collaboration between rheumatologists and dermatologists in the clinical and research domains.11,12

Despite Dr. Wright’s robust contributions to the literature in his studies on PsA, the publication record on this subject was relatively scant. A review of Medline publications between 1970 and 1990 reveals that 128 manuscripts were published on PsA compared with 23,926 on RA during the same time span. Scientific studies during this era focused on genetic associations with class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) alleles and clinical trials with agents such as 1.25-dihydroxyvitamin D, gold compounds, interferon-γ, and methotrexate. For the most part, these trials were underpowered or open label, and a small number of subjects were enrolled. To complicate matters, outcome assessments were not standardized or validated. PsA had definitely not hit the mainstream in the rheumatology community. However, in the late 1990s, the field of research changed dramatically with the arrival of new laboratory techniques and a novel class of therapeutic agents.

TABLE 2: Historical and Clinical Landmarks in Psoriatic Arthritis

- Genetics

- Association with MHC class I alleles, IL-1 cluster, TNF, IL-23R, AND IL-12

- IL-23R and CW-6 have stronger links to PsA and MICA stronger association with PsA

- Histopathologic features of psoriatic synovium

- Increased vascularity

- Histologic features more similar to other PsA than RA

- Absence of antibodies to shared epitope

- Elevated levels of TNF in the synovial tissue and fluid

- TH1 and possibly TH17 immune response

- Enthesitis

- A site of inflammation or origin of disease?

- Synovial–enthesial complex comprised of multiple structures subject to biomechanical stress and inflammation

- Bone marrow edema

- Aberrant bone remodeling

- Overexpression of RANKL and increased levels of circulating OCP

- Bone resorption fueled by TNF

- Increased pathologic bone formation linked to BMP molecules and possibly the Wnt signaling pathway

- Psoriatic disease

- Clustering of disorders including psoriasis, arthritis, uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular disease

- Prominent contribution from monocyte effector cells

Nurture Versus Nature

Evidence supporting a link with MHC class 1 alleles in PsA was published soon after the association of HLA-B27 with ankylosing spondylitis was established. A major impediment to the study of genetics in PsA is the need to separate patients with joint and skin manifestations. Recent data using genome-wide association scans have identified a number of genes that segregate with PsA, although it appears that Cw6 and IL-23 have stronger links with the skin disease, while major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related gene A (MICA) alleles are associated more closely with the arthritis.13 Much interest has focused on the contribution of infections and trauma, which may favor the development of arthritis, although the importance of these environmental factors is not well established.14

Synovial Studies

The study of psoriatic synovium was ushered in by the findings of Espinoza et al. that revealed unique histopathologic and ultrastructural findings in the blood vessels traversing the synovium.15 Subsequent research by Reese et al. in Leeds followed by studies from De Rycke et al in Belgium showed that PsA synovium had histopathologic features that were more akin to other forms of PsA than RA, particularly in regards to the presence of neutrophils, prominent vascularity, and lining layer hyperplasia.16,17 Additional studies have identified a plethora of cytokines; the most prominent are tumor necrosis factor (TNF), vascular endothelial growth factor, and interleukin (IL)-1. Although analysis of psoriatic skin has uncovered a central role for IL-17 and IL-22 in cutaneous inflammation, the importance of Th17 cells in PsA is a matter of debate.18 Synovial studies focused on IL-17 have not been published, and a recent clinical trial with ustekinumab, a molecule that blocks both IL-12 and IL-23, was rather unimpressive compared with the clinical trial data with anti-TNF agents.19

Enthesis: Interesting Linchpin or Focus Inflammation?

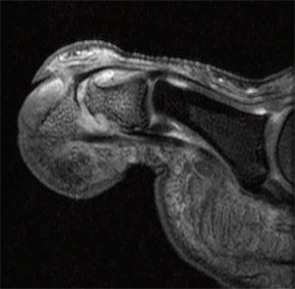

Imaging studies performed by Dr. McGonagle and others uncovered widespread signals in the bone marrow in PsA subjects. They noted focal bone marrow edema (BME) adjacent to entheseal insertions and more generalized BME at distant sites in some patients. They also noted the close proximity of entheseal attachments to other important structures such as synovium, bursa, and fibrocartilage. Based on these observations, they proposed the concept of the synovio-entheseal (SEC) complex to explain the origins of psoriatic joint and tissue inflammation.20 In this model, the interaction between local mechanical forces and structures in the SEC trigger cytokine release via an innate immune response, and these cytokines promote tissue inflammation. This model combines dysfunction at the local level with an aberrant inflammatory response. Other investigators acknowledge an important contribution of the entheses, but they challenge the concept that this structure is the initial focus of inflammation. The presence of osteitis is often striking on MRI in PsA patients and studies, but the pathologic correlate of this radiographic term has been controversial. MRI imaging and histopathologic studies of arthritic TNF transgenic mice revealed that BME represents expansion of monocytes in the bone marrow (see Figures 1A, p. 19, and 1B, p. 20) that corresponds with BME signals on MRI.21

Aberrant Bone Marrow Remodeling

One of the most intriguing features of PsA is the tendency for marked bone resorption and pathologic new bone formation.22 Moreover, this aberrant remodeling can take place in the peripheral joints and axial skeleton. Histopathologic studies revealed high receptive activator of nuclear factor kappa–B ligand (RANKL) expression in PsA synovium and elevated levels of osteoclast precursors (OCP) in the circulation of PsA patients. The OCP are exquisitely sensitive to TNF blockade, and levels of these cells are increased in some psoriasis patients without musculoskeletal symptoms, suggesting that these cells may be susceptibility markers for arthritis, although additional confirmation is required. Recent studies have uncovered a number of possible pathways that lead to pathologic bone formation, but emphasis is now centered on bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) and other molecules that modulate the Wnt signaling pathway, such as Dickkopf (DKK-1) and sclerostin.23

Psoriatic Disease

In the majority of patients, psoriasis precedes arthritis by about 10 years. Epidemiologic studies have shown a high prevalence of obesity that is an incident risk factor for psoriasis.24 It has also become apparent that patients with psoriasis often manifest associated disorders at a higher prevalence than controls. Recently described mechanisms that link obesity and inflammation raise the possibility that obesity may contribute to psoriasis onset in patients with certain genetic backgrounds. Other disorders, besides arthritis, that aggregate with psoriasis are diabetes, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and premature atherosclerosis.25 A contributing role for monocyte effector cells in fostering disease at these disparate sites has been proposed.

![Figure 1B: Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin stain [H&E]; left panels) and MRI features (right panels) in TNF transgenic (Tg) mice and wildtype (WT) littermates without the transgene. Note the striking bone marrow edema in the Tg mouse. This finding correlates with an expansion of red marrow as shown. Staining of the cells revealed an expansion of CD11b+ monocytes but not lymphocytes.](https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/wp-content/uploads/springboard/image/THR_2009_08_pp20_01.jpg)

Lessons from Clinical Trials

As outlined in this article, great advances have occurred in our knowledge of some of the mechanisms that are responsible for PsA. Advances at the bench, however, have been accompanied by remarkable improvements in therapy for PsA and psoriasis. The TNF inhibitors have proven to be extremely effective for both the skin and joint disease in many patients.26 Surprisingly, anti–T cell agents such as efalizumab and alefacept have proven modestly effective for psoriasis but not for PsA, and efalizumab was recently recalled due to concerns over progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Other agents that have potential for the treatment of PsA aside from ustekinumab are abatacept, rituximab, anti-RANKL antibody, and antibodies to IL-6R and IL-17. In many cases, financial support from pharmaceutical companies fueled the advance of clinical trial design and outcome measures and in some cases supported studies focused on disease mechanisms.

Dr. Wright would have appreciated the great upsurge in interest in PsA, and he would have been an active member of GRAPPA. If he were alive today, Dr. Wright would surely champion additional collection of information, and he would embrace clinical and scientific advances even if they challenged his earlier findings. Indeed, it is likely that the diverse subsets first proposed by Dr. Wright reflect heterogeneous disease pathways that we are still attempting to understand, and perhaps different therapeutic strategies will be required depending on the clinical phenotype. Armed with sophisticated tools for laboratory investigation, genetic analysis and imaging investigators will no doubt unveil new disease mechanisms and formulate new paradigms to explain the remarkable clinical phenotypes of PsA first described by Dr. Wright more than 50 years ago.

Dr. Ritchlin is a professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, N.Y. Dr. Helliwell is senior lecturer in rheumatology at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom.

References

- Bauer W, Bennett GA, Zeller JW. The pathology of joint lesions in patients with psoriasis and arthritis. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1941;56:349-352.

- Wright V. Rheumatism and psoriasis: A re-evaluation. Am J Med. 1959;27:454-462.

- Baker H, Golding DN, Thompson M. Psoriasis and arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1963;58:909-925.

- Blumberg, BS, Bunim JJ, Calkins E, Pirani CL, Zvaifler NJ. Nomenclature and classification of arthritis and rheumatism (tentative) accepted by the American Rheumatism Association. Bull Rheum Dis. 1964;14:339-340.

- Moll, JM, Wright V. Familial occurrence of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1973; 32:181-201.

- Macrae I, Wright V. A family study of ulcerative colitis. With particular reference to ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1973;32:16-20.

- Wright V, Moll JM. Seronegative Polyarthritis. Amsterdam: North Holland;1976:488.

- Helliwell, P, Marchesoni A, Peters M, Barker M, Wright V. A re-evaluation of the osteoarticular manifestations of psoriasis. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:339-345.

- McGonagle D, Gibbon W, Emery P. Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. Lancet. 1998;352:1137-1140.

- Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665-2673.

- Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, et al. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1167-1170.

- Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008. [Epub ahead of print].

- Nograles KE, Brasington RD, Bowcock AM. New insights into the pathogenesis and genetics of psoriatic arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2009;5:83-91.

- Pattison E, Harrison BJ, Griffths CE, Silman AJ, Bruce IN. Environmental risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis: Results from a case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; 67:672-676.

- Espinoza LR, Vasey FB, Espinoza CG, Bocanegra TS, Germain BF. Vascular changes in psoriatic synovium. A light and electron microscopic study. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:677-684.

- Reece RJ, Canete JD, Parsons WJ, Emery P, Veale DJ. Distinct vascular patterns of early synovitis in psoriatic, reactive, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1481-1484.

- De Rycke L, Kruithof E, Vandooren B, Tak PP, Baeten D. Pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis: Insights from synovial membrane studies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006. 8:275-282.

- Johnson-Huang LM, McNutt NS, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. Cytokine-producing dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory skin diseases. J Clin Immunol. 2009; 29:247-256.

- Gottlieb A, Menter A, Mendelsohn A, et al. Ustekinumab, a human interleukin 12/23 monoclonal antibody,for psoriatic arthritis: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet. 2009;373:633-640.

- McGonagle D, Lories RJ, Tan AL, Benjamin M. The concept of a “synovio-entheseal complex” and its implications for understanding joint inflammation and damage in psoriatic arthritis and beyond. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2482-2491.

- Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, et al. Elucidating bone marrow edema and myelopoiesis in murine arthritis using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2019-2029.

- Mensah KA, Schwarz EM, Ritchlin CT. Altered bone remodeling in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:311-317.

- Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, et al. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nature Med. 2007;13:133-134.

- Setty AR, Choi HK. Psoriatic arthritis epidemiology. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:449-454.

- Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis: From skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:698-706.

- Mease PJ. Psoriatic arthritis therapy advances. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:426-432.

- Wright V. Psoriasis and arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1956;15:348-356.