Relapsing polychondritis (RPC) is a systemic and, in some cases, fatal disease. Dyspnea with findings of small airway disease—even in the absence of the more commonly associated tracheobronchial abnormalities or pathognomonic clinical findings, such as saddle nose and cauliflower ear—may be presenting signs and symptoms of relapsing polychondritis.

Below, we present a case demonstrating that pulmonary compromise may be overlooked as an initial clue to the diagnosis. Misattribution of signs and symptoms to asthma or infection can delay proper assignment of a diagnosis. Our case suggests atypical pulmonary involvement may include fleeting pulmonary infiltrates.

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old woman developed a dry cough progressively over three months, along with persistent shortness of breath, all following an upper respiratory tract infection. Initial treatment with a five-day course of oral prednisone and inhaled albuterol improved the cough, but the dyspnea worsened. Intensification of inhalation therapy with fluticasone with albuterol for two months did not improve symptoms.

Pulmonary function testing demonstrated forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) of 2.26 L (85% of predicted), total lung capacity (TLC) of 4.3 L (96% of predicted) and residual volume/TLC (RV/TLC) of 45% (145% of predicted), suggesting air trapping, but with no response to bronchodilators. Symptoms progressed to include night sweats, myalgias, worsening cough and shortness of breath, which culminated in an emergency department visit.

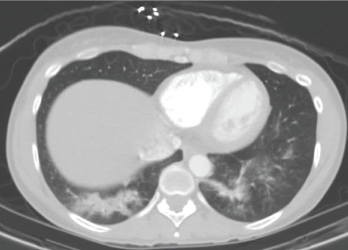

A CT scan of the chest performed in the emergency department shows bilateral infiltrates of the lower lobes.

A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (see Figure 1). Outpatient treatment with levofloxacin resulted in no improvement. Repeat pulmonary function testing showed worsening of air trapping (RV/TLC of 50%, 159% of predicted), as well as a paradoxical worsening of obstruction with bronchodilators (FEV1 change of 1.76 L, 66% of predicted; after bronchodilators it equaled 1.23 L, 46% of predicted).

Because the patient continued to experience night sweats, myalgia, worsening cough and dyspnea, prednisone was started as empirical treatment at 60 mg–100 mg daily, resulting in symptomatic improvement. Attempts to taper the prednisone were followed by a re-emergence of symptoms, along with new pleuritic chest pain, chest wall tenderness and a new left knee effusion. The patient also reported several years of ear pain that would wake her up at night, as well as nose redness and nose bridge pain.

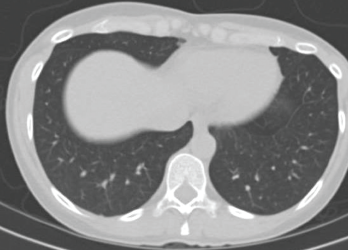

A repeat CT scan four weeks after high-dose prednisone demonstrated complete resolution of the infiltrates (see Figure 2).

Physical Exam

Pulmonary auscultation revealed a prolonged expiratory phase. The musculoskeletal evaluation confirmed a tender left knee effusion by way of the bulge sign, right patellar ballottement and costochondral and bilateral wrist tenderness. There was no saddle nose deformity, no cauliflower ear and no evidence for mononeuritis multiplex. Cutaneous stigmata for vasculitis were not present. A complete ophthalmic examination was benign. Formal audiology testing was normal.

Laboratory Evaluation

A CT scan taken four weeks after treatment was initiated with high-dose prednisone shows complete resolution of the infiltrates.