Relapsing polychondritis (RPC) is a systemic and, in some cases, fatal disease. Dyspnea with findings of small airway disease—even in the absence of the more commonly associated tracheobronchial abnormalities or pathognomonic clinical findings, such as saddle nose and cauliflower ear—may be presenting signs and symptoms of relapsing polychondritis.

Below, we present a case demonstrating that pulmonary compromise may be overlooked as an initial clue to the diagnosis. Misattribution of signs and symptoms to asthma or infection can delay proper assignment of a diagnosis. Our case suggests atypical pulmonary involvement may include fleeting pulmonary infiltrates.

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old woman developed a dry cough progressively over three months, along with persistent shortness of breath, all following an upper respiratory tract infection. Initial treatment with a five-day course of oral prednisone and inhaled albuterol improved the cough, but the dyspnea worsened. Intensification of inhalation therapy with fluticasone with albuterol for two months did not improve symptoms.

Pulmonary function testing demonstrated forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) of 2.26 L (85% of predicted), total lung capacity (TLC) of 4.3 L (96% of predicted) and residual volume/TLC (RV/TLC) of 45% (145% of predicted), suggesting air trapping, but with no response to bronchodilators. Symptoms progressed to include night sweats, myalgias, worsening cough and shortness of breath, which culminated in an emergency department visit.

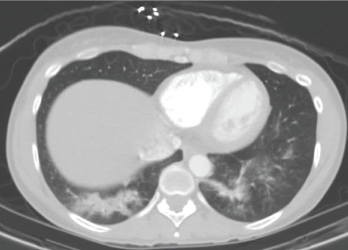

A CT scan of the chest performed in the emergency department shows bilateral infiltrates of the lower lobes.

A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (see Figure 1). Outpatient treatment with levofloxacin resulted in no improvement. Repeat pulmonary function testing showed worsening of air trapping (RV/TLC of 50%, 159% of predicted), as well as a paradoxical worsening of obstruction with bronchodilators (FEV1 change of 1.76 L, 66% of predicted; after bronchodilators it equaled 1.23 L, 46% of predicted).

Because the patient continued to experience night sweats, myalgia, worsening cough and dyspnea, prednisone was started as empirical treatment at 60 mg–100 mg daily, resulting in symptomatic improvement. Attempts to taper the prednisone were followed by a re-emergence of symptoms, along with new pleuritic chest pain, chest wall tenderness and a new left knee effusion. The patient also reported several years of ear pain that would wake her up at night, as well as nose redness and nose bridge pain.

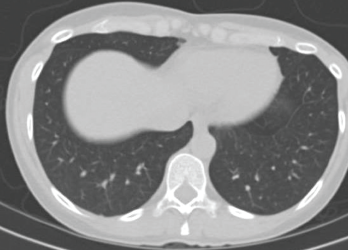

A repeat CT scan four weeks after high-dose prednisone demonstrated complete resolution of the infiltrates (see Figure 2).

Physical Exam

Pulmonary auscultation revealed a prolonged expiratory phase. The musculoskeletal evaluation confirmed a tender left knee effusion by way of the bulge sign, right patellar ballottement and costochondral and bilateral wrist tenderness. There was no saddle nose deformity, no cauliflower ear and no evidence for mononeuritis multiplex. Cutaneous stigmata for vasculitis were not present. A complete ophthalmic examination was benign. Formal audiology testing was normal.

Laboratory Evaluation

A CT scan taken four weeks after treatment was initiated with high-dose prednisone shows complete resolution of the infiltrates.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 8 mm/hour, and renal studies were normal. Eosinophilia was not evident on the peripheral blood smear. The following tests were all negative or normal: anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (with myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3 specificity), anti-double stranded DNA antibody, complement studies, anti-extractable nuclear antibody, cryoglobulins, anti-glomerular basement membrane, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C, anti-human immunodeficiency virus, rapid plasma reagin and the lymphocyte stimulation assay for tuberculosis.

At this point, it was possible to confirm a diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis using the Damiani et al. criteria, including non-erosive seronegative polyarthritis, a positive response to corticosteroids, costochondritis, and nasal and auricular chondritis.

Discussion

Pulmonary involvement due to RPC can affect up to 50% of patients. Although dyspnea is the most frequent respiratory symptom, patients commonly experience voice changes and severe throat pain.1 Complications due to respiratory compromise are likely due to uncontrolled chronic inflammation and include tracheomalacia, subglottic stenosis, air trapping and tracheobronchial wall thickening resulting in stenosis or tracheobronchomalacia. In unrecognized cases, these complications could prove fatal. Most studies show that airway disease, airway collapse and recurrent respiratory infections are associated with the greatest mortality in this population.2-5

Despite the more aggressive course of RPC when presenting with pulmonary features, these patients are often misdiagnosed. It has been hypothesized that diagnosis is complicated by the high frequency of respiratory complaints in the general population combined with the relative obscurity of this disease and the lack of specific biomarkers.6

Prior to diagnosis, our patient featured a progressive, unproductive cough and worsening dyspnea, with pulmonary infiltrates of noninfectious etiology. The patient responded favorably to high-dose steroid therapy, with subsequent imaging showing complete resolution of the pulmonary infiltrates.

Despite initial concerns for upper airway inflammation, small airway disease was the predominant feature of lung involvement in this patient, with air trapping demonstrated on pulmonary function testing. This was an unusual finding based upon published literature. In a 2009 retrospective analysis of 31 RPC patients with airway involvement, it was reported that nearly all patients (30/31) who underwent a bronchoscopy and/or CT chest imaging had at least one of the following four findings: subglottic stenosis, tracheal/tracheobronchial wall thickening, tracheobronchial malacia or tracheal wall calcifications.7

We found only one other documented RPC case of steroid-responsive noninfectious pulmonary infiltrates on imaging without tracheobronchial abnormalities. The patient described in 1992 by Burlew et al. was a 78-year-old man who had similar presenting symptoms, including dyspnea, intermittent voice hoarseness, cough, failure to respond to antibiotic treatment and ultimate objective response to high-dose steroid therapy.8 Additionally, withdrawing steroid therapy led to recurrence of pulmonary disease, and re-challenge with high-dose steroids resulted in resolution. In this report, the patient had bleeding after biopsy, and it was hypothesized the mechanism of the pulmonary infiltrates was vasculitis.

Relapsing polychondritis can affect not only the airways, but also the lung parenchyma. Early recognition and treatment of airway involvement can help prevent end organ damage.

Marcela A. Ferrada, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), Bethesda, Md.

Anjali Takyar, MD, works at the Crozer-Chester Medical Center, Upland, Pa.

James D. Katz, MD, works at NIAMS, Bethesda, Md.

Acknowledgment

This review was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ferrada MA, Grayson PC, Banerjee S, et al. Patient perception of disease-related symptoms and complications in relapsing polychondritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Aug;70(8):1124–1131.

- Michet CJ, Jr, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986 Jan;104(1):74–78.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al., Relapsing polychondritis: Prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976 May;55(3):193–215.

- Pearson CM, Kline HM, Newcomer VD. Relapsing polychondritis. N Engl J Med. 1960 Jul 14;263:51–58.

- Hughes RA, Berry CL, Seifert M, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Three cases with a clinico-pathological study and literature review. Q J Med. 1972 Jul;41(163):363–380.

- Hazra N, Dregan A, Charlton J, et al. Incidence and mortality of relapsing polychondritis in the UK: A population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015 Dec;54(12):2181–2187.

- Ernst A, Rafeq S, Boiselle P, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and airway involvement. Chest. 2009 Apr;135(4):1024–1030.

- Burlew BP, Lippton H, Klinestiver D, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: New pulmonary manifestations. J La State Med Soc. 1992 Feb;144(2):58–62.