Key Points

- The quality conversation is now evolving to the concept of value for patients—outcomes achieved per dollar spent.

- Defining good quality measures and improving performance is hard work and takes time.

- Most quality metrics have focused on processes of care, but patient-reported outcomes and overuse of high-cost medical interventions are new areas of interest.

- The time to act is now—if rheumatologists don’t lead the quality movement, it will be too late.

What does it mean to provide good quality of care to our rheumatology patients? How do we measure quality and demonstrate its presence to regulatory agencies, third-party payers, and our patients? With the rapid pace of change and increasing cost of healthcare delivery, there is a renewed interest in improving the quality of care, though these questions are not easy to answer. The time to think about how we as rheumatologists deliver high-quality care is now. The ACR has published a White Paper that describes the College’s perspective on the approach to quality measurement.1 Efforts are currently underway by the ACR to develop robust quality measures in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), gout, and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Yet, in order to demonstrate that we are improving health outcomes and creating value for our patients, we will need to do more.

Defining Quality Healthcare

The Institute of Medicine defines quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”2 Michael Porter, PhD, of the Harvard Business School in Boston, suggests a different approach that defines value as outcomes achieved per dollar spent.3 In this context, quality takes into account outcomes and efficiency, so that all the stakeholders in the healthcare system are aligned with the same goal in mind: providing care that is of highest value to the patient. This premise may also require a change in the reimbursement system, from a traditional fee-for-service framework to a bundled payment model.

Often, “quality metrics” have little to do with outcomes and more to do with process measures—which may (or may not) lead to an appropriate outcome. It is for this reason and others that we have difficult time defining quality measures. Is it sufficient to simply order a test—such as a bone density—to meet a quality metric? Should outcomes always be imputed as a necessity for any quality metric to be considered good? The real issue is the cost of care, as we spend 17% of GDP on healthcare costs, and yet our quality outcomes are questionable. A 2007 report from the Commonwealth Fund observed that “compared with five other nations—Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom—the U.S. healthcare system ranks last or next to last on five dimensions of a high-performance health system: quality, access, efficiency, equity, and healthy lives.”4 While there have been improvements in the approach to quality of care since then, these observations suggest a steep learning curve ahead.

Quality Metrics in the Rheumatology Clinic

For instance, if we applied this to RA, we could try and understand this concept more easily. How do we know that our expensive new therapies are actually improving health outcomes in RA? To determine “cost,” we must determine the expense of the entire spectrum of care for the RA patient, from office visits to medications to hospitalizations, and determine the aggregate cost per patient. To determine the value of this care, we would need to measure predefined valid outcomes of care such as disease activity score, radiographic progression, functional status score, quality of life, etc. By acknowledging cost and outcomes, we can then compare the value of the delivered care. One can imagine that, to improve the value of care (the equation of outcomes/cost), we will have to improve efficiency by eventually redesigning our care delivery system to be patient centered to optimize efficiency. This may also include expanded use of technology to track disease activity and functional status in real time, substitute frequent office visits with proactive telephone outreach to patients who are doing well, employ physician extenders, and even schedule comprehensive multidisciplinary visits for patients on one day at one location. Ultimately, we would be able to understand if the changes we made to the entire system of delivering care to RA patients actually resulted in an improvement in value.

As rheumatologists, it may be easiest for us to focus on our treatment of patients with RA, since the quality of RA care has been the best studied of our rheumatic diseases.5 There is currently a first-generation set of RA quality measures that are used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). These include the documentation of disease activity, functional status, disease prognosis, tuberculosis testing prior to biologic initiation, glucocorticoid management plans, and the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. Physicians can submit data on their patients to CMS through PQRS in order to qualify for the bonus payment offered for reporting on quality measures. Does meeting this set of RA quality metrics confirm that quality care is being provided? Does the corollary hold true? Does failing to achieve these measures indicate poor care delivery? The answers to these questions are at the core of the debate about defining quality care.

Can we define the optimal quality metrics that are worth measuring? Not easily. Developing quality metrics that are clinically meaningful and improving performance through quality improvement activities takes both time and a shift in culture. For example, in our institution we were interested in seeing how often our clinic patients who were treated with immunosuppressive therapies were up to date with appropriate vaccinations. In preliminary studies, we observed that, in the majority of patients, we failed to provide vaccinations for pneumococcal disease or influenza—our initial rates of pneumococcal vaccination were below 50%, a somewhat surprisingly low number for a large, referral academic center.

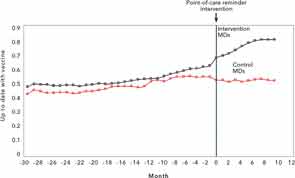

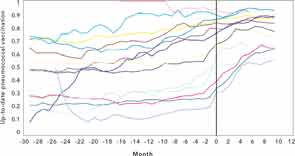

Since the first step in improving quality is to develop measurement tools and set targets for achievement, we developed an electronic system to track the frequency of pneumococcal vaccination in our immunosuppressed rheumatology patients.6 We created lists of patients who did not meet the vaccination guidelines established by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the ACR. We shared our data regularly with clinical staff, and provided rheumatologists with their monthly personal performance scores. However, it was not until we introduced a paper-based reminder attached to the billing sheet used at the point of care that we were able to substantially increase our rates of vaccination (see Figure 1).7 These efforts took considerable time and required a change in attitude on the part of staff members, including nurses, practice assistants, and rheumatologists, as well as patients. It was interesting to see just how different the vaccination rates were among rheumatologists and how much improvement was possible with a practical, paper-based reminder (see Figure 2). Just as our performance has achieved near 90% compliance, the CDC guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination for immunosuppressed patients were modified, increasing the complexity to conform to newer guidelines! Pneumococcal vaccine is just one of many quality indicators worth measuring and, as we observed, the workflow implications from this exercise of enhancing compliance are not trivial in a busy office practice. Yet this effort may pale in comparison to future vaccination efforts, such as providing zoster vaccine to our patients.

Perhaps we should take a surgical approach to these issues, as our colleague, Atul Gawande MD, MPH, professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston, has suggested, and employ a “checklist” to remind rheumatologists of the things that need to be done when managing complex patients.8 Checklists have been used successfully in other healthcare settings, such as in the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit and reducing mortality in the operating room. For patients starting DMARDs, either biologic or nonbiologic, there is a list of activities that one needs to review: age- and disease-specific vaccines, hepatitis testing, results of baseline blood counts, renal and hepatic function, tuberculosis screening, and discussion of risks/benefits of the DMARD, to name just a few.

To see whether we could influence physician behaviors, we created a paper checklist and posted it in our clinic examination rooms. The results were disappointing. What we learned is that, without an electronic checklist that is more integrated with clinical workflow, checklists may not be regularly utilized.

Source: Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:39-47.

Source: Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:39-47.

Fitting the Patient into the Equation

How does the patient fit into the paradigm of quality of care? Patients have an evolving role in their disease management—particularly in many of the chronic diseases that we see, such as RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and the vasculitides. With the increasing use of electronic health records that provide patient portals and the wide array of health information available on the Internet, many patients are able to access their own health information online and ask savvy questions about their diseases and their medications.

Engaging patients in their disease management can be an effective way to help improve patients’ satisfaction with their care. When patients understand the rationale for using more aggressive treatment strategies in RA and the real risks and benefits of the medications we prescribe, there may be a better adherence to the treatment plan, which can hopefully achieve better outcomes, such as low disease activity or remission.9 This experiment is being carried out in Sweden, where RA patient registries with web-based tools help patients track their own disease activity. It will be interesting to see whether they will play a role in changing the model of RA care delivery. Innovations such as smartphone applications, kiosks in the clinic, or computer tablets in the waiting room can help collect relevant data from our patients in a more efficient manner and enable us to make better decisions about disease management during the office visit.10 For example, integrating a disease activity tool into the electronic medical record provides rheumatologists with the ability to view important trends over time at the point of care.11

The Gorilla in the Room: Cost of Care

With the advent of so many options to treat RA and the efficacy of biologic DMARDs, the issue of controlling costs becomes critical. Adalimumab is the highest-grossing drug in the world, with sales approaching $9 billion.12 With emerging data suggesting that some patients may stay in remission even when using lower doses of biologic drugs, there may be opportunities to achieve good clinical outcomes while still lowering overall cost, thereby leading to high-value care for our patients.13 However, defining “outcomes” in a chronic disease like RA remains challenging. Should it be the absence of radiographic progression, or is it clinical remission as defined by a DAS-28, CDAI, or RAPID3 scores, or is it simply global functional status? Radiographic outcomes are not routinely calculated in clinical practice and thus are not readily available as a way to measure RA outcomes. Standardized assessments of disease activity are not performed on every patient at every visit in every rheumatology clinic—and even when they are done, the same instrument may not be used, so comparing outcomes may be inconsistent across patients or practices. Lastly, although patient-reported outcomes are gaining popularity and arguably may represent the most important perspective on RA, we need to understand how to best incorporate this data into our busy clinical practices. Do we feel confident that we, as rheumatologists, will find the time to regularly perform these measures of disease activity and utilize the data effectively?

Making our Efforts Meaningful

What about testing overuse? To think critically about efficiency of care, the ACR has partnered with the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) in the “Choosing Wisely” campaign to develop a “Top 5” list of commonly ordered tests, treatments, or services used in rheumatology, but whose utility is questioned. They include: antinuclear antibody and Lyme antibody testing, the role for magnetic resonance imaging and bone densitometry, and the use of biologic DMARDs (see Table 1). How this list will be used in the clinic and whether it may lead to reduced costs or improved outcomes remains to be seen.

With rising pressure to improve access to care and the fiscal need to see more patients as reimbursements decline and sequesters expand, it may become even more difficult to document and prove quality outcomes. The rising prevalence of electronic medical records encourages us to use them in a more “meaningful” way—but the additional responsibilities of the office staff and rheumatologists to enter data into the electronic medical records cannot be understated. Whether the adoption of the Medicare-supported Meaningful Use program actually improves the care our patients receive remains to be seen.14 Given the projections of demand for rheumatology care not being met by adequate supply, efficiency of care will become essential.15 Newer models of care, such as immediate access clinics, may allow for earlier diagnoses and initiation of therapy.16 We are at a critical point in the healthcare debate. We will need to define and measure our quality outcomes and value, or others may do it for us.

Dr. Desai is associate physician in the department of medicine, divisions of rheumatology, immunology, and allergy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Coblyn is director of clinical rheumatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

References

- Saag KG, Yazdany J, Alexander C, et al. Defining quality of care in rheumatology: The American College of Rheumatology white paper on quality measurement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken).2001;63:2-9.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC; 2001.

- Porter ME. What is value in healthcare? N Engl J Med. 2011;363:2477-2481.

- Davis K, Schoen C, Stremikis K. Mirror, mirror on the wall: How the Performance of the U.S. healthcare system compares internationally, 2010 update. The Commonwealth Fund. June 2010.

- Desai SP, Yazdany J. Quality measurement and improvement in rheumatology: Rheumatoid arthritis as a case study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3649-3660.

- Desai SP, Turchin A, Szent-Gyorgyi LE, et al. Routinely measuring and reporting pneumococcal vaccination among immunosuppressed rheumatology outpatients: The first step in improving quality. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:366-372.

- Desai SP, Lu B, Szent-Gyorgyi LE, et al. Increasing pneumococcal vaccination for immunosuppressed patients: A cluster quality improvement trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:39-47.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499.

- Fraenkel L, Peters E, Charpentier P, et al. Decision tool to improve the quality of care in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:977-985.

- Ovretveit J, Keller C, Forsberg HH, Essen A, Lindblad S, Brommels M. Continuous innovation: Developing and using a clinical database with new technology for patient-centred care—The case of the Swedish quality register for arthritis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:118-124.

- Collier DS, Kay J, Estey G, Surrao D, Chueh HC, Grant RW. A rheumatology-specific informatics-based application with a disease activity calculator. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:488-494.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1369125/

- Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:918-929.

- Jha AK. Meaningful use of electronic health records: The road ahead. JAMA. 2010;304:1709-1710.

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:722-729.

- Gartner M, Fabrizii JP, Koban E, et al. Immediate access rheumatology clinic: Efficiency and outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:363-368.