To start, RA appears to be a disease of relatively recent onset. Medical anthropologists have sifted through burial sites for evidence of RA in both the New and the Old Worlds, with radically different findings. Rothschild and Woods published the earliest findings from Indian burial ground skeletons in the Ohio River Valley in the U.S.1 Even after thousands of years, the joints of the skeletons examined by the researchers retained the typical destructive patterns of RA: symmetry, damage to small joints more so than large joints, and sparing of the lower spine.

In contrast to the Americas, skeletal evidence for RA prior to the 1700s in Europe, Asia and Africa is fragmentary and unconvincing. RA’s rarity in the Old World until relatively recent times may explain why the first recognized description of RA in the European medical literature was not until 1800 by the French physician Dr. Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais.2 The name rheumatoid arthritis itself was not coined until 1859 by British rheumatologist Dr. Alfred Baring Garrod.3

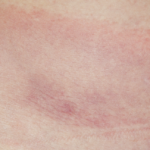

For millions of people around the world where disease-modifying treatment is unavailable, this is the natural history of RA: chronic pain, relentless joint destruction, immobility, early death.

But if RA simmered for thousands of years in the Americas, what events led to its establishment in Europe and beyond? Infections are transmitted in the blink of an eye; the transmission of smallpox, a virus previously unknown to Native Americans and spread by European settlers, led to the rapid extinction of entire tribes up and down the Eastern Seaboard of the Americas. The emergence of RA in Europe didn’t follow the usual pattern of infection. Whole families were not afflicted. Sporadic cases were the rule. Seemingly, it just appeared.

Paul Ehrlich, an early 20th century German physician, coined the term Horror Autotoxicus to capture the frightening concept that immune system cells can, in certain circumstances, damage the very organs they’re designed to protect.4 Today, we recognize RA as an autoimmune disease. But there has always been a lingering question of whether infection might act as a triggering event for the disease. In recent decades, however, despite our ability to increasingly identify life at the molecular level, no persistent infection has been documented in the joints of patients with RA.

If it’s true that there is no straight line between infection and RA, recent work in genetics and oral health has led researchers to reconsider the role of chronic infection as a permissive factor for the development of RA. For decades, it’s been recognized that the HLA-DR4 gene is a risk factor for both RA and a seemingly unrelated inflammatory condition, periodontal disease.

Low doses of prednisone can improve pain & swelling [in RA], but slower acting medications, such as methotrexate, sometimes in combination with … Enbrel or Remicade, enable us to successfully manage this terrible disease.

One particular bacterium in chronic periodontal disease, P. gingivitis, has come under increasing scrutiny. P. gingivitis has the singular ability to citrullinate peptides (substituting a citrulline amino acid for alanine). The altered citrullinated peptides could then be recognized as non-self by the immune system and, in an as yet poorly understood manner, trigger a cascade of immunologic events leading to the development of RA. Bolstering this theory is the recognition that antibodies against citrullinated peptides (CCP antibodies) not only appear years before RA patients develop their disease, but can be isolated from the joints of RA sufferers.