PHILADELPHIA—Emerging data have indicated an association between anti–tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) therapy with the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

According to Michael D. Iseman, MD, professor emeritus in the division of respiratory and infectious diseases at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver, diagnosis of NTM lung disease is often delayed and can result in significant morbidity or death.

Speaking here at the recent ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting, Dr. Iseman said that patients should be screened prior to initiation of anti–TNF-α therapy and then closely monitored for NTM disease and tuberculosis (TB). Prevalence of NTM lung disease is greater than that of TB in the United States, he said.

“Rheumatoid arthritis disease patients are at increased risk of mycobacterial infections and fungal infections due to immunocompromising therapy or the lung damage associated with immunological disease. Both TB and non-TB mycobacterial infections are potentially life threatening,” Dr. Iseman said. “The price of freedom from mycobacterial infections in this era of rheumatologic disease therapy is eternal vigilance.”

Patients at High Risk

Patients most at risk for NTM are elderly women and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, silicosis, sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis, chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, and rheumatoid ankylosing spondylitis. Also, healthy young women who are taller than average have been identified as high risk if they are slender and have a low body mass index, narrow anteroposterior diameter, subtle scoliosis, mitral valve prolapse, and hypomastia, he said.

Dr. Iseman reviewed data from research by Kevin L. Winthrop, MD, and colleagues that were recently published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.1 Winthrop and colleagues reported that patients using infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab are at increased risk for granulomatous infection, including activation of latent TB. This research found the highest incidence in patients using infliximab (73 cases), followed by etanercept (25 cases) and adalimumab (seven cases).

In that research, investigators reviewed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MedWatch database, a voluntary system, for reports over a five-year period of NTM disease in patients who were using anti–TNF-α therapy. Among the 105 cases that met the NTM disease criteria, 70% had RA, and most were elderly women. In addition to the TNF therapy, most patients were taking prednisone or methotrexate.

For most of the patients, the lung was the most frequently reported site of infection, they said, with the remainder extrapulmonary or disseminated. Those patients with pulmonary NTM lung disease were more likely to have underlying RA.

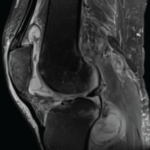

The researchers said that a chest radiograph “is not sufficiently sensitive for detecting bronchiectasis or other lung abnormalities associated with NTM disease.” They recommended that clinicians obtain a noncontrast chest computed tomography (CT) scan before giving this therapy to patients who may be at risk.

Dr. Iseman said that physicians should consider any patient with a history of chronic cough or recurrent pneumonia as being at potential risk for NTM with initiation of anti–TNF-α therapy. Patients at risk should be screened by chest X-ray and CT scan, with additional sputum screening for AFB. Any patient needing treatment with anti–TNF-α should be referred to an infectious disease specialist or pulmonologist before initiation of the therapy, Dr. Iseman said.

Dr. Winthrop and colleagues also reported the results of a survey of infectious disease physicians, which found that the cases of NTM disease associated with anti–TNF-α therapy “occur twice as frequently as cases of TB,” and that these diseases are likely not reported as frequently to the FDA as reports about TB.1

While advising that it is unclear from their research whether it is safe to reinstitute anti–TNF-α therapy in patients diagnosed with NTM, Dr. Winthrop and colleagues note that “it is not possible to definitively conclude that [the therapy] causes or is associated with NTM disease.” Certainly, they said, NTM is underreported, and their findings “highlight that these cases are occurring in such patients, often with devastating outcomes.”1

Latent TB

Although the incidence of TB in the United States is declining within the general population, certain populations are at high risk: immigrants, minorities, the homeless, substance abusers, the elderly, healthcare workers, and those who are immunocompromised due to AIDS, oncology therapy, organ transplantation, or use of biologics, Dr. Iseman said.

TB is spread human to human and is an airborne infection, he said. “Depending on the reception that your immune system gives to the infection, it may progress rapidly in multiple weeks to a near life-threatening disease. For patients infected with AIDS who are then infected with TB, death can occur within four weeks.” For others, TB can be dormant for any length of time, even up to seven decades. “The obligation to screen for latent TB before putting someone on biologics is explicit,” he said.

The tuberculin skin test (PPD) is often used for screening of latent TB, but it is neither sensitive nor specific. The skin test cross-reacts with people who have had BCG vaccination, given in most parts of the world but not in the United States. About 25% of people with active TB do not react positively to the tuberculin skin test, he said.

Interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are more specific than skin tests and are probably more sensitive, but they can give false negatives, Dr. Iseman said. “We don’t yet know their predictive value over time, indeterminate results are common, and they are expensive and technically restrictive,” he said.

A better screening method, he said, involves several steps:

- Complete history, including information related to race, ethnicity, poverty status, travel, country of origin, and occupation;

- A physical exam to identify nodes and abscesses;

- TB skin test;

- IGRAs;

- A chest X-ray; and

- Questions about prednisone use for one month or longer or use of TNF-α therapy.

As an example of the value of patient history, Dr. Iseman reviewed the case of a 47-year-old woman who lived in Manila, Philippines, for more than 40 years and had been a nurse’s aide as a young person. Her skin test was negative, and she did not test positive on IGRA.

For high-risk patients, such as the nurse’s aide, a 5-mm induration on the skin test should be considered positive, whereas 10 mm is considered positive for people not at high risk, Dr. Iseman said. For patients with a negative skin test and positive IGRA, there is high likelihood of latent TB. For patients with a negative skin test and negative IGRA but other risk factors, such as travel or work in healthcare, there is no assurance that the patient is free of latent TB. The cutoff point for IGRA assays should be lower in high-risk patients, he said.

Treatment Options for Latent TB

Dr. Iseman reviewed the latest American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for treatment of latent TB. These guidelines recommend the following drug regimen:

- Isoniazid therapy for nine months; or

- Isoniazid therapy for six months; or

- Rifampin for four months.

- Rifampin/pyrazinamide should not be offered for treatment.

Also, treatment of latent TB should be used for two to four weeks before beginning a TNF-α agent. Patients can be serially reinfected with TB and continue to be vulnerable, he said. “So you have to be aggressive for looking out for reinfections.” Patients infected with multidrug resistant TB will require more complicated therapy.

Kathy Holliman is a medical journalist based in New Jersey.