When evaluating a patient’s pain, whether consciously or not, a doctor may allow mistaken beliefs to affect their interpretation of a patient’s symptoms and, thus, treatment decisions.

Chad Zuber/shutterstock.com

In the world of evidence-based medicine, basing diagnosis and treatment decisions on belief instead of data seems anachronistic. And yet … clinicians are human, and humans live in culture, and culture is formed by beliefs, and beliefs (consciously or unconsciously) drive perception and, often, action.

So a new study shining a light on racial bias in the way pain is assessed and treated doesn’t come as a surprise, but it does highlight the continued need for clinicians to be aware of the seepage of beliefs into their practice and the ways it may interfere with good clinical care.

“Physicians are trained to determine the etiology and severity of patients’ symptoms and to treat patients accordingly,” says Ernest R. Vina, MD, University of Arizona Arthritis Center, Tucson, Ariz. “During the evaluation process—although unconscious (or possibly conscious)—bias may influence how physicians interpret patients’ symptoms.”

In the study, investigators from the University of Virginia focused on the beliefs held by white medical students and residents about biological differences between black and white people and how these beliefs are linked to racial bias in pain perception and treatment recommendations. In specific, the study looked at whether white people with medical training held false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites, and whether this influenced pain diagnosis and treatment recommendations.

The study found that a substantial number of white medical students and residents hold false beliefs about biological differences between white and black persons. Those false beliefs predict racial bias in pain perception, and this bias extends to treatment recommendations.

Ms. Hoffman

“We’ve known for a long time that there are huge disparities in how blacks and whites are assessed and treated by the medical community,” says lead author of the study, Kelly M. Hoffman, PhD candidate in social psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia. “Our study provides some insight into what might contribute to this—false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites.”

These false beliefs are not new and have historically been used to justify slavery and the inhuman treatment of black persons in medicine, Ms. Hoffman says, adding that one striking finding is that the false beliefs held today are not necessarily related to individual prejudice.

“Many people who reject stereotyping and prejudice nonetheless believe in these biological differences,” Ms. Hoffman says, adding that the study suggests these false beliefs could be contributing to racial disparities in pain management and causing harm to patients.

A ‘lack of empathy for black individuals is a proximal cause of pain treatment biases.’ —Dr. Drwecki

A Look at the Data

That racial bias in pain assessment and treatment exists is not a new finding. Several studies show that black patients receive lower quality pain treatment than white patients, including those presenting to the emergency department.2

What is new in the study by Hoffman and colleagues, according to Robert Edwards, PhD, Department of Anesthesiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, is the examination of false beliefs and “the discovery that holders of these false beliefs are more likely to exhibit racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations.”

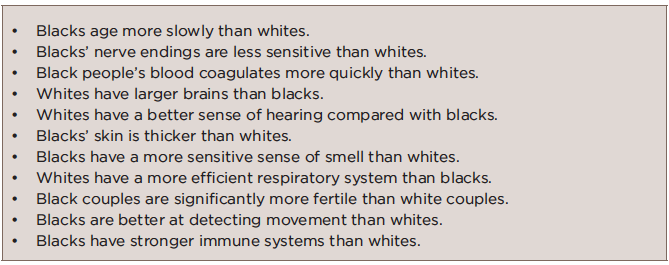

In the second part of the two-part study (the first part looked at beliefs among white laypersons), 222 white medical students and residents were given two case studies (one of a black patient and the other of a white patient) and asked to estimate their pain and make a treatment recommendation. They were then asked to complete a list of beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Table 1 (below) lists the 11 false beliefs reported.

TABLE 1: False Beliefs Held by Participating Medical Students & Residents

Source: Ref. 1, Table 1.

The study found that the white medical students and residents who held these false beliefs about biological differences showed racial bias in their perception and treatment recommendations, and specifically rated the black patients’ pain as lower than white patients’ pain, which resulted in less accurate treatment recommendations for black patients.

Highlighting that most of the white medical students and residents sampled held inaccurate beliefs about fictional differences, Dr. Edwards also points out that they failed to report actual differences supported by the evidence (e.g., a higher risk for heart disease and stroke in blacks compared with whites).

With regard to pain, he says that “it is especially unfortunate that some people seem to assume blacks are less sensitive to pain than whites, because a good deal of research suggests the opposite—that individuals from an ethnic minority background tend to show greater sensitivity to pain and susceptibility to many chronic, disabling pain conditions.”

A Different Shade of Racial Bias?

Among the research showing that black people may actually have enhanced pain sensitivity is a study published in 2014 that found that black patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) displayed increased pain sensitivity to noxious stimuli (e.g., thermal heat, punctuate pressure and cold pressor task) and greater increases in pain when receiving repetitive pulses of heat and pressure (i.e., temporal summation) than white patients.3 These findings held true after adjusting for education and annual income.

Dr. Bradley

“This suggests that central sensitization is greater among African American persons with knee osteoarthritis and may contribute to enhanced clinical pain,” according to Laurence A. Bradley, PhD, professor of medicine, Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), a co-author of the study.

Dr. Bradley is one of several investigators at the University of Florida and UAB collaborating on a study of ethnic differences in pain among adults with OA through a grant funded by the National Institute of Aging, The research points to the need to better understand what underlies the ethnic differences in pain responses, as well as change in these responses. To examine this, the investigators are conducting a five-year longitudinal study to look at biological and psychosocial variables that may contribute to ethnic differences in pain at baseline, as well as change in pain two years later.

Results of the longitudinal study will help determine what differences in biological and psychosocial variables may contribute to the enhanced perception of pain found among black patients with OA. Until then, evidence from the 2014 study that suggests there is a biological difference between black and white persons in pain perception raises the question of whether this may lead to another form of racial bias when diagnosing and treating pain in patients.

What do clinicians do with this sort of information? How will these data affect treatment recommendations? Will black patients be offered higher doses of pain medications? Will white patients be undertreated?

Complexity of Treatment Bias

Highlighting the complexity of the impact of beliefs on action (i.e., treatment recommendations) is a finding in the study by Hoffman and colleagues that found no racial bias in treatment recommendations among white medical students and residents who did not endorse or endorsed fewer false beliefs about black patients and also reported that white patients experienced less pain than black patients.

Unlike the white medical students and residents who held false beliefs that blacks felt less pain than whites and therefore recommended inaccurate treatment, the opposite wasn’t true among those students and residents who did not endorse or endorsed fewer false beliefs about black patients and reported that white patients experienced less pain. In this case, no racial bias was seen in treatment recommendation.

“It thus seems that racial bias in pain perception has pernicious consequences for accuracy in treatment recommendations for black patients and not for white patients,” say the authors in the study.1

Complicating treatment recommendations for pain are psychosocial variables that also play a role in the access to pain treatment for different populations. Data show that pharmacies in nonwhite communities are less likely to carry analgesics.4,5 In one study, the main reasons for not carrying adequate supplies of analgesic opioids were regulations regarding disposal, illicit use and fraud; low demand; and fear of theft.5

When placed in the current controversy over opioid use and the emerging public health problem of opioid overdoses, these data make it increasingly challenging for clinicians to provide the best treatment for pain to their patients. Discounting biological differences altogether—even in the face of emerging evidence of differences (e.g., blacks exhibiting a heightened sensitivity to pain)—may lead to inaccurate treatment recommendations in the same way that holding false beliefs (e.g., blacks experience less pain) does.

In the charged environment in which we live—when any talk of racial differences automatically equates to discrimination or bias—the challenge is to do what good medicine does: gather data, look at the data, openly share and discuss the data, and apply the best response and resources to them.

When placed in context of the current controversy over opioid use & the emerging public health problem of opioid overdoses, these data make it increasingly challenging for clinicians to provide the best treatment for pain to their patients.

Providing Good Clinical Care

Good clinical care begins with good medical education. In an article written for the AMA Journal of Ethics on identifying and combating racial bias in pain treatment, Brian B. Drwecki, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Regis University, Denver, emphasizes medical education as potentially the most valuable tool to reducing racial bias in healthcare.6 Among the factors he highlights as important for reducing bias in medical education is the need to collect data to better understand and ameliorate racial disparities. To that end, he encourages requiring medical students to participate in research pools to examine hypotheses regarding medical decision-making processes that include the effects of racial bias.

Overall, he emphasizes that his own research indicates that a “lack of empathy for black individuals is a proximal cause of pain treatment biases.”

For Dr. Edwards, empathy-oriented interventions combined with education may reduce biases. Empathy-oriented interventions could include imagining oneself in the situations of others and trying to understand the obstacles others face. “It may be beneficial for healthcare providers to reflect on how difficult and challenging it can be for some patients to seek treatment from our healthcare system,” he says. “For example, many patients face issues ranging from difficulty understanding their insurance coverage to arranging transportation to affording medical care costs to, sometimes, dealing with suspicious or biased providers.”

Saying he sympathizes with the challenges faced by clinicians when trying to determine how best to treat pain in their patients, Dr. Bradley emphasizes the need for clinicians to be aware that many patients have an enhanced sensitivity to pain that appears to be biologically related.

“When one observes enhanced patient pain behavior that is not consistent with clinical findings, one must consider whether it is appropriate to provide recommended levels of medication or other treatments for pain,” he says.

“However, one must also consider that there are subgroups of persons who display enhanced pain sensitivity related to altered central nervous system function or other factors that are not yet identified,” he says, adding that he and his colleagues will continue to improve their understanding of ethnicity and pain to provide help to clinicians.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in Minneapolis.

Resources

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016 Apr 19;113(16):4296–4301.

- Todd KH. Influence of ethnicity on emergency department pain management. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2001 Sep;13(3):274–278.

- Cruz-Almeida Y, Sibille KT, Goodin BR, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Jul;66(7):1800–1810.

- Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, West B, Washington T. Differences in prescription opioid analgesic availability: Comparing minority and white pharmacies across Michigan. J Pain. 2005 Oct;6(10):689–699.

- Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, et al. ‘We don’t carry that’—Failure of pharmacists in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med. 2000 Apr 6;342(14):1023–1026.

- Drwecki BB. Education to identify and combat racial bias in pain treatment. AMA J Ethics. 2015 Mar;17(3):221–228.