Advances in medical and information technology, such as online data registries and advanced genetic analysis methods, are driving new opportunities in rheumatic disease research, especially for rare diseases. While rare diseases by definition affect only a small portion of the population—a rare disease affects fewer than 200,000 people, according to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration—research on these conditions serves the broader medical community in multiple ways, including improving patient outcomes, increasing efficiency of therapies and advancing knowledge of disease-related pathways, which can lead to new targeted therapies for both rare and common diseases.

Advances in medical and information technology, such as online data registries and advanced genetic analysis methods, are driving new opportunities in rheumatic disease research, especially for rare diseases. While rare diseases by definition affect only a small portion of the population—a rare disease affects fewer than 200,000 people, according to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration—research on these conditions serves the broader medical community in multiple ways, including improving patient outcomes, increasing efficiency of therapies and advancing knowledge of disease-related pathways, which can lead to new targeted therapies for both rare and common diseases.

Jonathan Miner, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Microbiology and Immunology Programs, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo., specializes in the intersection of innate immunity, antiviral immunity and autoimmunity. His team is currently studying several ultra-rare diseases, such as retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy (RVCL) and stimulator of interferon genes (STING) associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI). Such diseases may affect only a few hundred individuals.

“My team works on diseases at the genetic and molecular level,” says Dr. Miner. “We approach research by asking what we can learn by comparing 50 patients with nearly identical clinical symptoms, rather than by studying hundreds or thousands of patients with matching diagnoses but varied symptoms.”

The Power of Information

A focus on symptoms can be especially important for patients with rare diseases, for whom getting an accurate diagnosis can be difficult.

Discovered in the 1980s, RVCL is a devastating disease that affects the brain, eyes, kidney, liver and, for some patients, the gastrointestinal tract and bones. In 2007, rheumatologist John Atkinson, MD, at Washington University, identified the dominant gene mutation that causes the disease. Individuals with the mutation invariably develop disease around age 40 or 50 and nearly all die within five to 10 years of disease onset. Despite ongoing research by Dr. Miner and his team, there is currently no therapy for RVCL. What’s more, many RVCL patients are misdiagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or multiple sclerosis (MS). Unfortunately, the therapies for SLE and MS are ineffective for RVCL and, in some cases, can exacerbate the condition.

Dr. Miner recalls one international family with RVCL, saying their “entire village believed them to be cursed. Throughout the generations, they had lost many family members by age 45. Once the medical team identified the patient’s disease and other family members also were diagnosed with RVCL, they could say it was not a curse; it is this mutation and this specific disease. While some patients may receive a difficult diagnosis like RVCL, which is difficult to treat, it is still empowering for patients to be able to understand their diagnosis and its implications.”

Better knowledge of rare diseases can improve diagnosis, reduce morbidity and streamline therapeutic decision-making. It can also help connect patients with the right treatments, clinical trials and supportive care, thus improving their outcomes.

Progress in rare disease research can also broaden the understanding of more common diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis or vasculitis. By grouping people based on nearly identical clinical features of disease, it becomes easier to determine the disease’s genetic basis. In contrast to the complex genetics of common diseases, the smaller pool of genetic data associated with a rare disease can simplify the discovery process and help researchers home in on an illness-causing mutation.

As Dr. Miner says, “When we understand a particular disease pathway that’s affecting patients with an ultra-rare disease, it leads us to study those same pathways in common diseases and can guide us toward novel therapeutic targets for those more common rheumatic diseases.”

Connecting the Dots

Increased access to data can further advance rare disease research. The internet has enabled patients and providers to more easily find information and connect around shared anomalies. More patients receive exome and genome sequences that can shed light on potential disease pathways. Providers are also increasing data sharing through registries and other means.

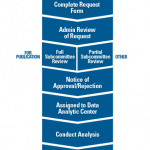

The ACR’s Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry collects data from electronic health records, including clinical note analysis. As a rheumatology-specific registry, RISE can provide data for research on rare rheumatic diseases. In the past five years, RISE data has been analyzed for four abstracts and two papers on rare rheumatic diseases, including ANCA-associated vasculitis and sarcoidosis.

Dr. Miner suggests that this is leading to the discovery of new patterns. “I often wonder how many of our patients with more common rheumatic diseases also have rare mutations—not just polymorphisms, but rare disease-causing variants—that haven’t been identified or characterized,” he says. As one example, mutations known to cause SAVI were recently found in some adults with ANCA-associated vasculitis, which is far more common.

“All clinicians see patients with syndromes presenting outside of the traditional, predictable ways,” Dr. Miner notes. “If there is only one RVCL patient in a practice, that patient could easily be misdiagnosed as having MS or SLE. When we don’t connect, we don’t learn of those uncommon cases in other practices. Increasing communication and data-sharing facilitates the proper diagnosis for our patients, helps us identify disease-causing mutations and is now leading to novel therapies that will likely benefit patients with common diseases.”

To get involved in data sharing to support and advance research, check out the ACR’s RISE registry.

Allison Plitman, MPA, is the communications specialist for the ACR’s RISE Registry.