But after five years, our confidence in what to do wanes. Do we continue therapy or do we stop? We know that bisphosphonates remain in bone matrix for many years until the drug is released and becomes active when the local bone packet is resorbed. These findings suggest the possibility that clinical efficacy may persist for a period of time even after the drug is stopped. Conversely, some concern has been raised about the possibility that prolonged reduced bone turnover might allow “microcracks” to accumulate, although there is no evidence to date that shows an increased fracture risk.

This study by Black and colleagues provides clinically useful information on both the effectiveness of continued bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk. One thousand ninety-nine women who had enrolled in the original FIT and had received alendronate for five years were randomized to receive five additional years of alendronate, five or 10 mg daily, or placebo.1 The primary outcome measure was total hip BMD; secondary measures were BMD at other sites, biochemical markers of remodeling, and fracture incidence.

Women taking placebo had mean declines in BMD of -2.4% at the total hip and -3.7% at the lumbar spine compared to pooled alendronate groups. These levels remained at or above pretreatment levels 10 years earlier. Serum markers of bone turnover increased but remained below pretreatment levels.

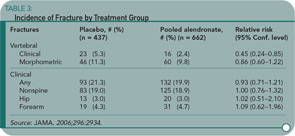

Despite the BMD declines, the cumulative risk of all nonvertebral fractures was no higher for those on placebo (18.9%) compared to alendronate (19%). (See Table 3) The risk for clinically recognized vertebral fractures was significantly lower in women who continued on alendronate (2.4% versus 5.3%). Further analysis of this group showed that the greatest reductions of fracture risk in women continuing on alendronate occurred in two groups: women with lowest T-scores (-2.5 or less) and those with baseline prevalent vertebral fractures. In other words, women without these high risk factors for clinical vertebral fractures did not demonstrate significant benefit by continuing to take alendronate.

In 18 women (nine placebo and nine alendronate) who had bone biopsies, there were no quantitative differences in histomorphometry, suggesting that bone turnover was not inordinately suppressed. No instances of jaw osteonecrosis were observed.

So, what might we counsel our postmenopausal patients on alendronate when they reach their five-year anniversary of starting the drug? For significant numbers of women, it is probably reasonable to stop alendronate and follow them closely with serial dual X-ray absorptiometry scans. The women who can stop therapy are those who’ve had good responses to bisphosphonate therapy and are not otherwise at high risk for vertebral fracture. For those women who remain at high risk of vertebral fracture by virtue of prevalent vertebral fractures or low T-scores (this study leaves uncertainty about how low), continued use of alendronate makes sense. For those women who continue the drug, we can probably calm their concerns—and ours—that continued use for 10 years does not increase their fracture risk.

Reference

Decompressive Surgery Better than Conservative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

By David G. Borenstein, MD