PPIs Increase Hip Fracture Risk

By Robyn T. Domsic, MD

Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947-2953.

Abstract

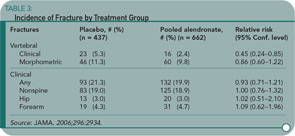

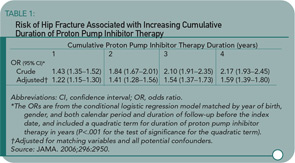

Context: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may interfere with calcium absorption through induction of hypochlorhydria but they also may reduce bone resorption through inhibition of osteoclastic vacuolar proton pumps. Objective: To determine the association between PPI therapy and risk of hip fracture. Design, setting, and patients: A nested case-control study was conducted using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) (1987–2003), which contains information on patients in the United Kingdom. The study cohort consisted of users of PPI therapy and nonusers of acid suppression drugs who were older than 50. Cases included all patients with an incident hip fracture. Controls were selected using incidence density sampling, matched for gender, index date, year of birth, and both calendar period and duration of up-to-standard follow-up before the index date. For comparison purposes, a similar nested case-control analysis for histamine-2 receptor antagonists was performed. Main outcome measure: The risk of hip fractures associated with PPI use. Results: There were 13,556 hip fracture cases and 135,386 controls. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for hip fracture associated with more than one year of PPI therapy was 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30–1.59). The risk of hip fracture was significantly increased among patients prescribed long-term high-dose PPIs (AOR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.80–3.90; P<.001). The strength of the association increased with increasing duration of PPI therapy (AOR for one year, 1.22 [95% CI, 1.15–1.30]; two years, 1.41 [95% CI, 1.28–1.56]; 3 years, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.37–1.73]; and four years, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.39–1.80]; P<.001 for all comparisons). Conclusion: Long-term PPI therapy, particularly at high doses, is associated with an increased risk of hip fracture.

Commentary

In the United States in 2005, there were more than 95 million prescriptions dispensed for PPIs in 2005, with total sales exceeding $12.8 billion. If we assume one prescription was given per patient, then approximately one-third of Americans were prescribed a PPI. This number is probably an underestimate considering the over-the-counter availability of PPIs. Thus, this study applies to a significant portion of our patients.

Yang and colleagues used a nested case-control study within the GPRD to examine the association of PPI therapy and hip fractures among individuals 50 or older. There were 192,028 eligible individuals receiving PPIs in the GPRD. Cases were eligible if individuals were followed at least one year in the database prior to suffering an incident hip fracture. Cases were matched up to ten-to-one with non-PPI users by gender, year of birth, index date, and calendar period. The primary exposure of interest was PPI therapy greater than one year before the index date. Steroid use was greater in the PPI users, and this was controlled for in the subsequent multivariate regression model. An additional nested case-control study was performed looking at users of histamine-2 receptor blockers. Shown here are the odds ratio by length of PPI therapy (see Table 1) and PPI or histamine-2 receptor blockers by dose (see Table 2). The results show an increasing risk of hip fracture with increasing duration and higher doses of PPI therapy. Not depicted in these tables is the presence of a stronger association between PPI therapy and hip fracture among men (OR 1.78 [95% CI 1.42–2.22]) than women (OR 1.36 [95% CI 1.22–1.53]), although there was a statistically significant interaction between PPI therapy and gender.

These results are similar to another case-control study published last year by Vestergaard et al. reporting an increased risk of hip fracture with PPI use (adjusted OR 1.45 [95% CI 1.28–1.65]) and spine fracture (OR 1.60 [95% CI 1.25–2.04]).1 That study did not find a dose-response to PPI use, but its methodology was different in determination of cases (all individuals with a fracture in Denmark during 2000), and they examined all individuals receiving a PPI as opposed to long-term use, which may account for the differences between the studies.

There are limitations to this study, as in all case-control studies. Not all confounders may have been measured or assessed. Exposure assessment status is always subject to bias, although, given the method of prescription capture in the GPRD and that omeprazole was not over-the-counter until 2004, this is probably minimal. Calcium supplementation could not be assessed and may be an important mediator.

This is a well done study linking PPI use with an increased risk of hip fracture that supports similar findings from earlier case-control studies. We recognize that patients who have undergone gastrectomy or are afflicted with pernicious anemia, and thus have achlorohydria, are at increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture. The animal and limited human data from patients with achlorohydria suggest that a potential mechanism may be reduced absorption of insoluble calcium salts in a non-acidic environment. This mechanism fits with the observation of a dose-response relationship in the current study. Certainly, this study raises many more questions, and I anxiously await further epidemiologic studies looking at associations of vertebral and other fracture risks, as well as animal data clarifying the effect of PPI use on calcium absorption.

At this time, I will not change my use of PPIs in my patient population, particularly since many of them have esophageal motility abnormalities. However, this study is enough to make me pause and educate my patients on the importance of twice-daily calcium supplementation with soluble calcium salts (such as calcium carbonate or calcium citrate) taken with a meal and an acidic beverage to try and increase absorption.

Reference

Stopping Alendronate at Five Years Not a Fracture Risk

By Eric S. Schned, MD

Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after five years of treatment—the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-Term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927-2938.

Abstract

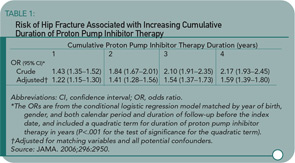

Context: The optimal duration of treatment of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis is uncertain. Objective: To compare the effects of discontinuing alendronate treatment after five years versus continuing for 10 years. Design and setting: Randomized, double-blind trial conducted at 10 U.S. clinical centers that participated in the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT). Participants: One thousand ninety-nine postmenopausal women who had been randomized to alendronate in FIT, with a mean of five years of prior alendronate treatment. Intervention: Randomization to alendronate, 5 mg/d (n = 329) or 10 mg/d (n = 333), or placebo (n = 437) for five years (1998–2003). Main outcome measures: The primary outcome measure was total hip bone mineral density (BMD); secondary measures were BMD at other sites and biochemical markers of bone remodeling. An exploratory outcome measure was fracture incidence. Results: Compared with continuing alendronate, switching to placebo for five years resulted in declines in BMD at the total hip (-2.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.9% to -1.8%; P<.001) and spine (-3.7%; 95% CI, -4.5% to -3.0%; P<.001), but mean levels remained at or above pretreatment levels 10 years earlier. Similarly, those discontinuing alendronate had increased serum markers of bone turnover compared with continuing alendronate: 55.6% (P<.001) for C-telopeptide of type 1-collagen, 59.5% (P < .001) for serum n=propeptide of type-1 collagen, and 28.1% (P<.001) for bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, but after five years without therapy, bone marker levels remained somewhat below pretreatment levels 10 years earlier. After five years, the cumulative risk of nonvertebral fractures (relative risk [RR], 1.00; 95% CI, 0.76–1.32) was not significantly different between those continuing (19%) and discontinuing (18.9%) alendronate. Among those who continued, there was a significantly lower risk of clinically recognized vertebral fractures (5.3% for placebo and 2.4% for alendronate; RR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.24–0.85) but no significant reduction in morphometric vertebral fractures (11.3% for placebo and 9.8% for alendronate; RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.60–1.22). A small sample of 18 transilial bone biopsies did not show any qualitative abnormalities, with bone turnover (double labeling) seen in all specimens. Conclusions: Women who discontinued alendronate after five years showed a moderate decline in BMD and a gradual rise in biochemical markers but no higher fracture risk other than for clinical vertebral fractures compared with those who continued alendronate. These results suggest that for many women, discontinuation of alendronate for up to five years does not appear to significantly increase fracture risk. However, women at very high risk of clinical vertebral fractures may benefit by continuing beyond five years.

Commentary

Most rheumatologists are comfortable treating patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis with oral bisphosphonates for up to five years. We’re used to seeing significant increases in BMD, and we are confident that we are preventing vertebral and nonvertebral fractures.

But after five years, our confidence in what to do wanes. Do we continue therapy or do we stop? We know that bisphosphonates remain in bone matrix for many years until the drug is released and becomes active when the local bone packet is resorbed. These findings suggest the possibility that clinical efficacy may persist for a period of time even after the drug is stopped. Conversely, some concern has been raised about the possibility that prolonged reduced bone turnover might allow “microcracks” to accumulate, although there is no evidence to date that shows an increased fracture risk.

This study by Black and colleagues provides clinically useful information on both the effectiveness of continued bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk. One thousand ninety-nine women who had enrolled in the original FIT and had received alendronate for five years were randomized to receive five additional years of alendronate, five or 10 mg daily, or placebo.1 The primary outcome measure was total hip BMD; secondary measures were BMD at other sites, biochemical markers of remodeling, and fracture incidence.

Women taking placebo had mean declines in BMD of -2.4% at the total hip and -3.7% at the lumbar spine compared to pooled alendronate groups. These levels remained at or above pretreatment levels 10 years earlier. Serum markers of bone turnover increased but remained below pretreatment levels.

Despite the BMD declines, the cumulative risk of all nonvertebral fractures was no higher for those on placebo (18.9%) compared to alendronate (19%). (See Table 3) The risk for clinically recognized vertebral fractures was significantly lower in women who continued on alendronate (2.4% versus 5.3%). Further analysis of this group showed that the greatest reductions of fracture risk in women continuing on alendronate occurred in two groups: women with lowest T-scores (-2.5 or less) and those with baseline prevalent vertebral fractures. In other words, women without these high risk factors for clinical vertebral fractures did not demonstrate significant benefit by continuing to take alendronate.

In 18 women (nine placebo and nine alendronate) who had bone biopsies, there were no quantitative differences in histomorphometry, suggesting that bone turnover was not inordinately suppressed. No instances of jaw osteonecrosis were observed.

So, what might we counsel our postmenopausal patients on alendronate when they reach their five-year anniversary of starting the drug? For significant numbers of women, it is probably reasonable to stop alendronate and follow them closely with serial dual X-ray absorptiometry scans. The women who can stop therapy are those who’ve had good responses to bisphosphonate therapy and are not otherwise at high risk for vertebral fracture. For those women who remain at high risk of vertebral fracture by virtue of prevalent vertebral fractures or low T-scores (this study leaves uncertainty about how low), continued use of alendronate makes sense. For those women who continue the drug, we can probably calm their concerns—and ours—that continued use for 10 years does not increase their fracture risk.

Reference

Decompressive Surgery Better than Conservative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

By David G. Borenstein, MD

Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara M et al. Surgical or Nonoperative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Spine. 2007;32:1-8.

Abstract

Study design: A randomized controlled trial. Objective: To assess the effectiveness of decompressive surgery as compared with nonoperative measures in the treatment of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Summary of background data: No previous randomized trial has assessed the effectiveness of surgery in comparison with conservative treatment for spinal stenosis. Methods: Four university hospitals agreed on the classification of the disease, inclusion and exclusion criteria, radiographic routines, surgical principles, nonoperative treatment options, and follow-up protocols. A total of 94 patients were randomized into a surgical or nonoperative treatment group: 50 and 44 patients, respectively. Surgery comprised undercutting laminectomy of the stenotic segments in 10 patients augmented with transpedicular fusion. The primary outcome was based on assessment of functional disability using the Oswestry Disability Index (scale, 0–100). Data on the intensity of leg and back pain (scales, 0–10) as well as self-reported and measured walking ability were compiled at randomization and at follow-up examination at six, 12, and 24 months. Results: Both treatment groups showed improvement during the follow-up. At one year, the mean difference in favor of surgery was 11.3 in disability (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.3–18.4), 1.7 in leg pain (95% CI, 0.4-3.0), and 2.3 (95% CI, 1.1–3.6) in back pain. At the two-year follow-up, the mean differences were slightly less: 7.8 in disability (95% CI, 0.8–14.9), 1.5 in leg pain (95% CI, 0.3–2.8), and 2.1 in back pain (95% CI, 1.0–3.3). Walking ability—either reported or measured—did not differ between the two treatment groups. Conclusion: Although patients improved during the two-year follow-up regardless of initial treatment, those undergoing decompressive surgery reported greater improvement regarding leg pain, back pain, and overall disability. The relative benefit of initial surgical treatment diminished over time, but outcomes of surgery remained favorable at two years. Longer follow-up is needed to determine if these differences persist.

Commentary

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a medical disorder that is increasing in frequency as the world’s population ages. Among the elderly, symptoms of back and leg pain are common problems although their etiology is diverse. Sophisticated imaging techniques, however, have identified a series of distinct anatomic abnormalities associated with narrowing of the spinal canal in the older lumbar spine, thereby increasing awareness of spinal stenosis as a cause of these symptoms as well as significant functional disability.

Although imaging techniques have facilitated the detection of spinal stenosis, the therapy of this entity remains uncertain. Major unresolved issues exist regarding the outcomes of non-operative and surgical therapy for spinal stenosis. For example, a long-term observational study of 10 years duration of 148 spinal stenosis patients assigned to surgery or non-operative therapy described early benefits of surgical intervention that waned over the duration of the investigation.1 Another issue involves the relative benefit of decompressive laminectomy with or without fusion. Randomized controlled trials addressing some of these issues were lacking until the study by Malmivaara and colleagues.

This two-year, randomized, controlled trial of 94 Finnish individuals about 63 years of age with moderate spinal stenosis showed greater benefit from surgery than medical therapy. (See Table 4) Patients with severe leg pain or neurologic deficits were excluded. Greater benefits with surgery were documented in disability and pain, but not walking ability. Of note is the finding of the gradual dilution of the beneficial effect of surgical intervention at two years. The 10 individuals with spinal fusion had less back and leg pain than non-fused surgical patients.

The Malmivaara study has significant limitations. For example, the duration of the study is short and patients need to be followed for a longer period of time to determine the durability of the benefit of surgical decompression. Also, I have major concerns about the nature and intensity of the non-operative therapy used. For example, in this study, medical therapy was defined as a choice of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and three sessions of physical therapy. No mention is made of patient satisfaction with their nonsteroidal therapy. Was more than one NSAID offered in the case of inefficacy or toxicity? Further, narcotic therapies were not offered as analgesics and the use of lumbar epidural injections was not mentioned. Thus, I believe that non-operative therapy was sub-optimal in this clinical trial.

The take-home message from this study is that non-operative and surgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis without severe neurologic deficits both offer reasonable outcomes for pain relief and improved function. The experimental evidence showing the clear benefit of non-operative versus surgical intervention is not extant. The authors suggest that non-operative therapy be the initial regimen with surgical therapy reserved for those who have persistent leg pain or physical dysfunction incompatible with activities of daily living. This is a recommendation for spinal stenosis therapy with which I concur.