CARDIOVASCULAR

RUTH Trial Urges Caution when Prescribing Raloxifene

By Robyn T. Domsic, MD

Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al. for the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) Trial Investigators. Effects of Raloxifene on Cardiovascular Events and Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women. NEJM. 2006;355:125-137.

Abstract

Background: The effect of raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, on coronary heart disease (CHD) and breast cancer is not established.

Methods: We randomly assigned 10,101 postmenopausal women (mean age, 67.5) with CHD or multiple risk factors for CHD to 60 mg of raloxifene daily or placebo and followed them for a median of 5.6 years. The two primary outcomes were coronary events (i.e., death from coronary causes, myocardial infarction, or hospitalization for an acute coronary syndrome) and invasive breast cancer.

Results: As compared with placebo, raloxifene had no significant effect on the risk of primary coronary events (533 versus 553 events; hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.07), and it reduced the risk of invasive breast cancer (40 versus 70 events; hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.38 to 0.83; absolute risk reduction, 1.2 invasive breast cancers per 1000 women treated for one year); the benefit was primarily due to a reduced risk of estrogen receptor–positive invasive breast cancers. There was no significant difference in the rates of death from any cause or total stroke according to group assignment, but raloxifene was associated with an increased risk of fatal stroke (59 versus 39 events; hazard ratio, 1.49; 95% confidence interval, 1.00 to 2.24; absolute risk increase, 0.7 per 1,000 woman-years) and venous thromboembolism (103 versus 71 events; hazard ratio, 1.44; 95% confidence interval, 1.06 to 1.95; absolute risk increase, 1.2 per 1,000 woman-years). Raloxifene reduced the risk of clinical vertebral fractures (64 versus 97 events; hazard ratio, 0.65; 95 % confidence interval, 0.47 to 0.89; absolute risk reduction, 1.3 per 1000).

Conclusions: Raloxifene did not significantly affect the risk of CHD. The benefits of raloxifene in reducing the risks of invasive breast cancer and vertebral fracture should be weighed against the increased risks of venous thromboembolism and fatal stroke.

Commentary

The role of raloxifene in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis has been in a state of flux because concerns about hormonal therapy arose with the Women’s Health Initiative trial. In patients unable to take a bisphosphonate, or in those who were merely osteopenic, raloxifene has nevertheless remained a treatment option. As we can recall, the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) trial, published in 1999, suggested a 30% relative risk reduction in vertebral fractures among women with osteoporosis treated for three years, and reported an increase in femoral neck and spine density with raloxifene.1 This drug was then approved for use in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis by the Food and Drug Administration.

A secondary analysis of the MORE trial suggested a reduction in the rate of invasive breast cancer, and the RUTH trial was powered to evaluate the incidence rates of invasive breast cancer and coronary events in users of raloxifene versus placebo. A predefined secondary analysis was the rate of vertebral fractures. The patients in this trial were postmenopausal and had either established coronary artery disease (CHD), or were at high risk for CHD defined as four cardiac risk factors.

While these patients may seem different from the average rheumatologist’s patient population, I suggest that the individuals in the RUTH trial resemble our patient populations more closely than many of us would like to admit—and certainly closer than the MORE patients. As the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of CHD is elucidated, we are recognizing the increased incidence of CHD in our populations and the high rates of traditional and disease-related CHD risk among patients with autoimmune illnesses.

From an evidence-based medicine perspective, there are few criticisms of the RUTH trial. It was well designed and well executed, with appropriate power to answer the primary clinical questions. A little less clear is its ability to answer the question on the prevention of vertebral fractures, although the greater numbers than the MORE trial suggest it can, plus it follows patients for a median of five years versus three.

There is no difference in coronary events between patients treated with raloxifene versus those taking placebo. However, the real question for the rheumatologist is whether or not the benefits of raloxifene therapy for reduction in vertebral fractures outweigh the risks of the drug in this group of patients.

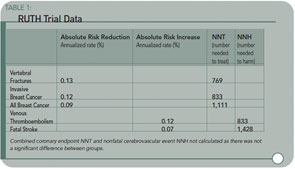

As the data from the RUTH trial indicate, the numbers needed to treat to prevent one vertebral fracture, or one incident of breast cancer, are essentially the same as the number of individuals treated to produce an adverse event. (See Table 1, below.) When combined with the null cardiovascular benefit, this study clearly highlights the potential risk of this medication for limited benefit in vertebral fracture reduction among patient populations at high risk of cardiovascular events—such as many of our rheumatologic patients. While the overwhelming majority of patients can take this drug safely, we need to take a look at the risk versus benefit ratio in each of our patients.

Reference

PEDIATRICS

Updating Juvenile Dermatomyositis Criteria

By Kathleen A. Haines, MD

Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, Davidson JE. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Rheumatology. 2006 Aug;45(8):990-993. Abstract and table reprinted with permission from the British Society for Rheumatology.

Abstract

Objective: To develop revised criteria for the diagnosis of juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) using an international consensus process.

Methods: An initial survey was circulated to members of the Network for JDM and the Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (PRINTO). Each individual was asked to identify those criteria that were felt to be most helpful in the diagnosis of classical JDM. A second survey was derived from these results and used to rank these proposed criteria in order of their importance and usefulness in clinical practice.

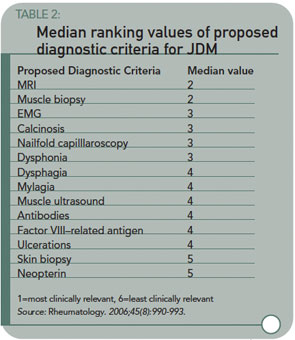

Results: The first survey had a response rate of 49.8% (118 individuals) from 92 centers in 32 countries. All responders routinely used proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin rash in the diagnosis of JDM, while 86.8% used elevated muscle enzymes. Muscle biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and changes on the electromyogram (EMG) were deemed important diagnostic criteria. Other criteria, including myositis-specific or -related antibodies, nailfold capillaroscopy, factor VIII-related antigen, muscle ultrasound, calcinosis, and neopterin were used by 35.3% of respondents. Seventy-eight respondents to the first survey (66%) responded to the second survey. Typical MRI and muscle biopsy changes were rated by all to be the most useful clinically relevant diagnostic criteria after proximal muscle weakness, characteristic skin rash, and elevated muscle enzymes. These were followed by myopathic changes on EMG, calcinosis, dysphonia, and nailfold capillaroscopy, which were ranked equally.

Conclusion: This process identified nine criteria that clinicians felt to be helpful or important in the diagnosis of JDM. A further process of refinement and validation is necessary to agree on an internationally acceptable, clinically usable set of diagnostic criteria.

Commentary

Evidence-based medicine requires studies; studies require accepted, well-standardized criteria. The Bohan and Peters criteria for dermatomyositis have served internist-rheumatologists well for more than 30 years. Pediatric rheumatologists have also used these criteria to advantage to make JDM diagnosis. However with advances in imaging technologies and the reluctance of pediatricians (and parents) to subject children to invasive procedures, many clinicians have drifted from the strict use of these criteria, primarily avoiding muscle biopsies and EMGs while retaining rash, proximal weakness, and elevated enzymes.

The authors have started the process of updating criteria for JDMS by a survey/consensus technique, identifying the diagnostic methods currently used, and found useful, by pediatric rheumatologists. Table 2 lists the diagnostic methods and the median usefulness rank for each. (See Table 2, above.) Magnetic resonance imaging of edema/inflammation in proximal muscles is taking the vote as a potential substitute for biopsy or EMGs. This also has its problems—cost, availability, and the fact that young children need to be sedated to get decent images.

What is not discussed but sorely needed—at least by me—are age- and size-adjusted normal values for muscle enzymes. Although a CK of 199 in a two-year-old may be “normal” by lab standards, it is way out of proportion to muscle mass. These authors address an important issue but the pediatric rheumatology community should take this opportunity to reconsider all of the old criteria as well as the invasive ones.

I would love to know which analytes are most sensitive indicators of myositis (CK, aldolase, and/or markers of endothelial activation such as VWF) and obtain age and body mass normal values. Similarly, age-related norms for muscle strength, using the CMAS (Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale-14), as was done for the earlier version CMAS9, would be useful for evaluating “how weak is weak.” Through the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society and CARRA (Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance) and their JDM interest sections, the community has the network to do these studies. Recruiting healthy children to donate a teaspoon of blood may be another story.

ARTHRITIS

Continued Debate on TNF Antagonists and Infection

By Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH

Dixon WG, Watson K, Lunt M, et.al. British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register Control Centre Consortium. Rates of serious infection, including site-specific and bacterial intracellular infection, in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2368-2376.

Abstract

Objective: To determine whether the rate of serious infection is higher in anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF)-treated RA patients compared with RA patients treated with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Methods: This was a national prospective observational study of 7,664 anti–TNF-treated and 1,354 DMARD-treated patients with severe RA from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. All serious infections, stratified by site and organism, were included in the analysis.

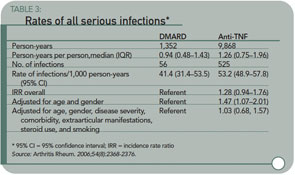

Results: Between December 2001 and September 2005, there were 525 serious infections in the anti–TNF-treated cohort and 56 in the comparison cohort (9,868 and 1,352 person-years of follow-up, respectively). The incidence rate ratio (IRR), adjusted for baseline risk, for the anti–TNF-treated cohort compared with the comparison cohort was 1.03 (95% confidence interval 0.68–1.57). However, the frequency of serious skin and soft tissue infections was increased in anti–TNF-treated patients, with an adjusted IRR of 4.28 (95% confidence interval 1.06–17.17). There was no difference in infection risk between the three main anti-TNF drugs. Nineteen serious bacterial intracellular infections occurred, exclusively in patients in the anti–TNF-treated cohort.

Conclusion: In patients with active RA, anti-TNF therapy was not associated with increased risk of overall serious infection compared with DMARD treatment, after adjustment for baseline risk. In contrast, the rate of serious skin and soft tissue infections was increased, suggesting an important physiologic role of TNF in host defense in the skin and soft tissues beyond that in other tissues.

Commentary

Just when you thought that the last word had been written on the risk of infection associated with TNF antagonists, another important observational study suggests that these drugs may not be associated with an increased risk in typical practice. The study from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register joins several other large analyses from cohorts showing no increased risk for infection associated with TNF antagonists.

For example, studies from the U.S. National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases and the U.S. Medicare system have found no increased risk of infection with TNF antagonists. While one observational study from the German Biologics Register (RABBIT) found an increased risk, the infection rate in the controls was surprisingly low; this raises the possibility that controls were drawn from a different source population or were followed in a different manner from the TNF antagonist patients.

The current study has some notable aspects. The authors found that 4% to 5% of patients had serious infections per year; this infection rate is consistent across several studies. (See Table 3, page 27, for details on the rates of serious infection in this study.) As expected, the severity of disease among patients taking TNF antagonists was greater than those on non-biologic DMARDs. Before severity adjusting, the rates of infection were higher among TNF antagonists, but the rate ratios equalized after accounting for severity.

However, the rates of intracellular infection were much higher among the TNF antagonists and the presentation of tuberculosis was atypical. In addition, there was a significant increase in the risk of soft tissue and skin infections among patients on TNF antagonists.

I will continue to discuss the possible risk of infection with patients starting TNF antagonists. My review of systems must continue to include infectious symptoms, focusing on the skin, soft tissue, and atypical manifestations of opportunistic infections. However, the current study adds to my sense that the benefits of TNF antagonists outweigh the risks.