GOUT

Singh JA, Jodges JS, Asch SM. Opportunities for improving medication use and monitoring in gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009; 68:1265-1270.

By Robyn T. Domsic, MD

Abstract

Study design: Cross-sectional analysis.

Purpose: To study patterns and predictors of medication use and laboratory monitoring in gout.

Methods: In a cohort of veterans with a diagnosis of gout prescribed allopurinol, colchicine, or probenecid, quality of care was assessed by examining adherence to the following evidence-based recommendations: 1) whether patients starting a new allopurinol prescription a) received continuous allopurinol, b) received colchicine prophylaxis, c) achieved the target uric acid level of ≤6 mg/dl; and 2) whether doses were adjusted for renal insufficiency. The association of sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare utilization, and comorbidity with the recommendations was examined by logistic/Poisson regression.

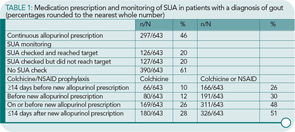

Results: Of the 643 patients with gout receiving a new allopurinol prescription, 297 (46%) received continuous allopurinol, 66 (10%) received colchicine prophylaxis, and 126 (20%) reached the target uric acid level of ≤6 mg/dl. During episodes of renal insufficiency, appropriate dose reduction/discontinuation of probenecid was done in 24/31 episodes (77%) and of colchicine in 36/52 episodes (69%). Multivariable regression showed that higher outpatient utilization, more rheumatology care, and lower comorbidity were associated with better quality of care; more rheumatology clinic or primary care visits were associated with less frequent allopurinol discontinuation; more total outpatient visit days or most frequent visits to a rheumatology clinic were associated with a higher likelihood of receiving colchicine prophylaxis; and a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index or more outpatient visit days were associated with higher odds of reaching the target uric acid level of ≤6 mg/dl.

Conclusion: Important variations were found in patterns of medication use and monitoring in patients with gout with suboptimal care. A concerted effort is needed to improve the overall care of gout.

Commentary

From an epidemiologic approach, gout is on the rise and is becoming a major public health problem. The prevalence in the United States has doubled since 1969, with an estimated 5.1 million affected people currently. The increasing incidence occurs most frequently in elderly men and postmenopausal women, and probably reflects the combined contribution of increasing longevity, increasing prevalence of comorbidities, and the high use rate of gout-predisposing medications such as diuretics and aspirin. The potential cost to our society of mismanaged gout is significant when one considers the associated disability. Thus, it is important that we all know how to manage gout and do it well. Using medications appropriately and understanding patient factors affecting use is key.

In this study, Singh et al identified a cohort of patients at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center database who received a new allopurinol or probenecid prescription between 1999 and 2003. Patients had to be followed by the VA two or more times over the year to ensure the VA had primarily responsibility for this medication management. The outcomes they examined included the percentage of patients receiving continuous allopurinol prescriptions, those who received colchicine or nonsteroidal antiinflammatroy drug (NSAID) prophylaxis with allopurinol initiation, the percentage who achieved the target serum uric acid (SUA) of ≤6.0, and the percentage who had colchicine or probenecid dosed for the presence of renal failure.

A cohort of 643 VA patients with a new allopurinol prescription managed by the VA was identified from a total of 3,658 patients with a gout diagnosis. The mean initial dose of allopurinol was 200 mg/day. A total of 125 patients receiving probenecid were identified, with over half of patients receiving 1,000 mg/day. The key results are depicted in Table 1 (above). Only 46% of patients filled a continuous prescription of allopurinol. As compliance with allopurinol dosing is notoriously low, this is not that surprising. What is eye opening, however, is the percentage of patients on allopurinol who did not have their SUA checked before death or when the study period ended (61%), and the fact that that only 20% reached the target SUA. Of those who did not achieve the target SUA, only 37% had an allouprinol dose change. Conversely, 24% of patients had a change in their allopurinol dose without a documented SUA. In regards to prophylaxis for acute gout flare with the initiation of allopurinol, 52% of patients did not receive a prescription for colchicine or NSAID at or before the onset of allopurinol.

The authors then performed multivariate analysis to examine associations between patient characteristics and the outcome measures. Allopurinol was discontinued less in patients with more primary care or rheumatology visits (an increase of 2.7 visits per year was associated with a 12% decrease in medication discontinuation). Patients with more outpatient visits were more likely to receive colchicine prophylaxis. Patients in rheumatology clinics had a 34% rate of colchicine prophylaxis, compared with other clinics with a rate of 6–8%. Patients with higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, an index assessing one-year mortality attributable to comorbidities, were less likely to obtain a target SUA.With respect to probenecid, only 42% of subjects had a subsequent creatinine check. In patients experiencing an episode of renal insufficiency while on probenecid, 77% had the drug stopped appropriately, while the remainder resolved their episode.

As a relatively recent trainee, gout was described to me as “bread and butter” rheumatology. The management seemed relatively simple because of few drug choices for treating either the acute flare or chronic tophaceous gout. Considering that flares rarely occur when the SUA level is less than 6 mg/dl, it seemed that all we need to do is try to keep the SUA level down. Simple, eh? In fellowship, I soon discovered that every attending had his or her own individual approach to management, and my challenge was to remember each attending’s preferences.

I like this article because it provides evidence-based medicine to support my observation that allopurinol has variable management in terms of follow-up and flare prophylaxis. The multivariate analysis suggests that generally rheumatologists do a better job than other physicians at prescribing flare prophylaxis with allopurinol, although clearly not good enough. I found the low rate of colchicine/NSAID prophylaxis started before or with allopurinol surprising. However, several prior reviews have postulated that inadequate gout flare prophylaxis may contribute to allopurinol discontinuation. The numbers provided here certainly support this line of reasoning.

Recently, the rheumatology community has been fortunate to see the FDA approval of febuxostat this year, with two more drugs (pegylated uricase and rilonacept) hopefully to follow suit. While these drugs have exciting prospects, the findings in the febuxostat APEX and FACT studies have suggested that the safety profile of allopurinol is good.1,2 Several editorials and commentaries on these studies have indicated that, for many individuals with chronic gout, more aggressive use and titration of allopurinol may be beneficial. The fact that over half of the patients did not have a follow-up SUA check in this study certainly suggests this may be the case.

The study does have some potential areas where it may underestimate drug and laboratory checks. Certainly, it is conceivable that patients may have had their SUAs checked closer to home, and did not make it into the VA system. However, I doubt this accounts for much of the 61% of missing SUA values. Also, it may be that certain nonsteroidal medications were bought over the counter, and thus may have been missed. The authors did perform a separate chart review for colchicine, and found that only 3% of patients had received a colchicine prescription from a non-VA source, which increases the confidence that colchicine use was not significantly missed.

Some may be tempted to read this and think, “I do a better job in my practice.” But is that really the case? Similar studies from the United Kingdom would suggest that we and primary caregivers don’t actually do better in managing gout that the results reported in the article.3 For those of us blessed with certain electronic medical records systems, it is easy enough to look at similar data for our own practice. From my perspective, after reading this study and the febuxostat trials, I am determined to pay more attention to followup uric acids and adjusting the allopurinol doses. And, when I’m on the consult service with the inevitable gout consults, I’ll take a little more time educating the patient and the residents and writing a detailed plan for management in the consult note. Hopefully, with everyone working together, we can diminish the impact of gout, which appears to be staging a serious comeback as one of the most common and disabling rheumatologic conditions.

Reference

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR, MacDonald PA, Lloyd E, Lademacher C. Clinical efficacy and safety of successful longterm urate lowering with febuxostat or allopurinol in subjects with gout. J Rheum. 2009; 36:1274-1282.

- Schumacher HR, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: A 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;29:1540-1548.

- Mikuls TR, Farrar JR, Biker WB, Vernandes S, Saag KG. Suboptimal physician adherence to quality indicators for the management of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: Results from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1038-1042