Bisphosphonates

Should Rheumatologists Watch for Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in Oral Bisphosphonate Users?

By Daniel Hal Solomon, MD, MPH

Sedghizadeh PP, Stanley K, Caligiuri M, Hofkes S, Lowry B, Shuler CF. Oral bisphosphonate use and the prevalence of osteonecrosis of the jaw: An institutional inquiry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:61-66.

Background: Initial reports of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) secondary to bisphosphonate (BP) therapy indicated that patients receiving BPs orally were at a negligible risk of developing ONJ compared with patients receiving BPs intravenously. The authors conducted a study to address a preliminary finding that ONJ secondary to oral BP therapy with alendronate sodium in a patient population at the University of Southern California was more common than previously suggested.

Methods: The authors queried an electronic medical record system to determine the number of patients with a history of alendronate use and all patients receiving alendronate who also were receiving treatment for ONJ.

Results: The authors identified 208 patients with a history of alendronate use. They found that nine had active ONJ and were being treated in the school’s clinics. These patients represented one in 23 of the patients receiving alendronate, or approximately 4% of the population.

Conclusions: This is the first large institutional study in the United States with respect to the epidemiology of ONJ and oral bisphosphonate use. Further studies along this line will help delineate more clearly the relationship between oral BP use and ONJ.

Clinical implications: The findings from this study indicated that even short-term oral use of alendronate led to ONJ in a subset of patients after certain dental procedures were performed. These findings have important therapeutic and preventive implications.

Commentary

ONJ has been increasingly described in relation to the use of bisphosphonates (BRONJ). The original reports of BRONJ focused on patients receiving intravenous (IV) bisphosphonates to treat osseous manifestations of a variety of cancers. In addition, numerous case series have been reported, some including patients using bisphosphonates at the lower dosages to treat osteoporosis. In the last two years, both the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) and the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research have put out major position papers regarding BRONJ.1,2 The AAOMS has established a case definition that includes three criteria: 1) An area of exposed bone within the oral cavity; 2) No predisposing conditions (such as oral radiation therapy); and 3) Prior use of a bisphosphonate. In addition, a grading system has been established by the AAOMS and general treatment recommendations have been put forward.

Among cancer patients, the epidemiology of BRONJ has been well defined. Large epidemiologic studies with careful follow-up and structured dental questionnaires and/or examinations have described an incidence of BRONJ ranging from 2% to 11%.3 Risk factors for BRONJ among cancer patients appear to be the concomitant use of glucocorticoids as well as several chemotherapies. Recent dental extractions strongly associate with BRONJ. However, the epidemiology of BRONJ among osteoporosis patients is much less clear.

Several sources suggest that the incidence of BRONJ among patients using these agents for osteoporosis is between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000.4 This estimate is based on sparse data, including the lack of BRONJ observed in randomized controlled trials with oral bisphosphonates. This number may be an underestimate because most trials did not formally assess for oral lesions. In fact, a postal survey conducted in Australia found a rate of BRONJ among oral bisphosphonate users between 0.01% and 0.04%. Rates increased 10-fold among persons with recent dental extractions.5

This more recent study by Sedghizadeh et al reported an even higher risk. Investigators at the USC dental school clinic collected a sample with all oral bisphosphonate users (n=208) and found nine cases of ONJ. None of the cases was referred to the clinic for ONJ, and all were at least stage 2 or 3 (painful or infected site of exposed bone). All cases of BRONJ occurred after a simple tooth extraction or denture trauma and all cases were among older women. No case occurred prior to 12 months of bisphosphonate exposure.

There were several limitations to the study by Sedghizadeh and colleagues. The dental school clinic population may not be representative of a typical population using bisphosphonates. The authors give us no information about the total source population. Also, the authors do not calculate the rate of ONJ among patients not using bisphosphonates. Thus, it is difficult to know whether the source population was uniquely at risk for ONJ.

Despite these potential limitations, the calculated rate of BRONJ of 4% is many times higher than other estimates. While it seems unlikely that the rate is actually this high, it is also likely that initial estimates of 1 per 100,000 were too low. However, without large well-conducted studies, there are no good estimates of the rates of BRONJ among osteoporosis patients. For now, it seems prudent to warn patients about this potential risk, to encourage them to have dental work prior to starting bisphosphonates, and then to include the oral cavity in one’s review of systems and physical examination of patients using bisphosphonates. If a patient needs dental work while on a bisphosphonate, they should have it done, but what to do with the bisphosphonate is unclear. The ASBMR task force noted that some experts suggest a period off of bisphosphonates before and after dental extractions.1 However, there are little actual data to guide decision making for such patients. As more patients have used bisphosphonates for longer periods, more cases of BRONJ are likely to surface. Based on potential toxicities and lack of clear benefit beyond five years, it may be prudent to limit bisphosphonate use to 60 months.

References

- Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: Report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007; 22:1479-1491.

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:369-376.

- Hoff AO, Toth BB, Altundag K, et al. The frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res. 2008; 23:826-836.

- Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw—Do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2278-2281.

- Mavrokokki T, Cheng A, Stein B, Goss A. Nature and frequency of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws in Australia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:415-423.

DXA

Increasing Bone Densitometry Testing Through an Outreach System

By Gail C. Davis, RN, EdD

Denberg TD, Myers, BA, Lin, CT, Libby, AM, Min SJ, McDermott MT, Steiner JF. An outreach intervention increases bone densitometry testing in older women. JAGS. 2009; 57:341-347.

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the performance of a patient recall intervention that relies on an outreach coordinator with a bachelor’s degree to prompt women by mail and telephone about their eligibility for bone densitometry (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA]) screening and allow them to schedule an examination without a medical provider visit ahead of time.

Design: Observational.

Setting: Academic general internal medicine practice.

Intervention: Mail- and telephone-based patient recall for DXA.

Participants: Five hundred sixty-four women aged 65 to 79 at average risk for osteoporosis without a history of DXA.

Measurements: Rates of DXA completion and the change in proportion of screened women during a seven-month intervention period, case finding for clinically significant bone loss, frequency of appropriate clinical follow-up, DXA no-show rates compared with usual care, and clinician satisfaction.

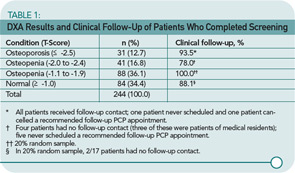

Results: Through patient recall, rates of DXA screening rose significantly (P<.001), and the proportion of the eligible clinic population screened increased 13%. Thirty percent of patients had clinically significant bone loss, with almost all of these receiving follow-up, DXA no-show rates were comparable with usual care, and provider acceptance was high.

Conclusion: A patient recall intervention substantially increased DXA screening, allowing pharmacological therapy to be started much earlier in some women with significant bone loss. It imposed minimal burden on providers and enhanced patient convenience. This type of program may have utility for additional preventive services.

Commentary

The article provides a description of a “health promotion outreach system” designed to “improve the delivery of preventive and chronic disease care in the outpatient setting.”1

Specifically, this outreach system was developed to increase DXA testing of bone density in women between the ages of 65 and 79 who were patients in an academic ambulatory medical practice. The recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is that DXA screening should routinely begin for postmenopausal women at age 65, and at age 60 for those who are at increased risk for osteoporotic fractures (e.g., low weight and no current hormone replacement therapy).2 Women aged 80 and over were excluded from the study because primary care providers (PCPs) preferred to see them prior to a DXA referral, assuming they might have more comorbidities than younger women. Women were also excluded if they were currently taking a bisphosphonate or had active cancer or a terminal diagnosis.

The authors make a case for the importance of the study, noting that the disability, mortality, and direct care costs associated with osteoporotic fractures could be reduced if screening were increased and treatment begun to maintain or increase bone density. They note that 50% of women aged 50 and older will have a future osteoporosis-related fracture.3 Further evidence pointing out the incidence and the issues associated with osteoporotic fractures is available and compelling.4,5

Prior to implementation of the intervention, it was approved by all of the PCPs in the system. An invitation letter was sent to 564 eligible patients that informed them of the USPSTF recommendations and encouraged them to call for a DXA appointment. Along with the letter, a prepaid postcard was included that individuals could return to indicate if they had had a previous DXA outside this agency, no longer received primary health care within this system, were not interested in receiving a DXA, or would like to be called at a given time and number. If there was no response to the first letter within two weeks, the coordinator called the patients up to three times over an eight-week period. If no response was received, a voice message was left only the first time. If the woman was reached, the coordinator reviewed the DXA recommendations and scheduled an appointment, if this was desired. An electronic order for the DXA was then requested from the PCP. When the DXA results were received, the PCP decided whether to follow up by mail, phone, or an office visit. A call center was available for patients to request a callback.

Results support the use of such an intervention in primary care. Almost half (n=244, 43.3%) of those contacted had a bone scan. Table 1 (p. 20) shows the results of those found to have osteoporosis, advanced osteopenia (defined as a T-score of less than -2.0), less severe osteopenia, and normal bone mass, as well as the follow-up activities. These numbers show that 72 women (29.5%) of those screened had clinically significant bone loss requiring pharmacological therapy. The treatment criteria of the National Osteoporosis Foundation indicate that pharmacological therapy should be started for those with a T-score equal to or less than -2.5 of the hip (femoral neck) or spine.6

This prevention model offers a feasible, positive approach to increasing patient participation in a potentially preventive activity such as DXA screening. The intervention was found to be valuable when outcomes were measured, and it was viewed as beneficial by the PCPs. The notes following Table 1 show that most patients received clinical follow-up, though nine of those with advanced osteopenia did not. Lack of follow-up was most often related to patients not following advice to make an appointment or to resident physicians not communicating with patients. In addition to increasing the preventive screening, such an intervention could promote education about the health-related condition while, at the same time, allowing more time during the office visit for discussion of the person’s more immediate health issues. The authors note that additional testing is needed in a variety of practice environments.

Implementation of such an intervention could be planned individually for different environments (e.g., rheumatology clinics and private practices). Because the cost of mailing and having staff available for calling may be prohibitive without additional funding, settings can at least take steps to insure that patients receive information as they make office visits. For example, a nurse or nurse practitioner could be designated to make a quick risk assessment and provide counseling before or after the patient sees the physician. Discussion might be prompted by signs placed in the waiting area (in English and other appropriate languages). In addition to the USPSTF recommendations, cost considerations should also be discussed with patients. Medicare will cover DXA every two years3; other insurers may vary. Not only women should be targeted; men with risk factors (e.g., aged 70 and older, low weight, and minimal exercise) should also be assessed.7

References

- Denberg TD, Lin CT, Myers BA, Cashman JM, Kutner JS, Steiner JF. Improving patient care through health-promotion outreach. J Ambul Care Manage. 2008;31:54-65.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force. Screening for Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. Release Date: September 2002 [online]. Available at www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Fast Facts on Osteoporosis. 2008 [online]. Available at www.nof.org/osteoporosis/diseasefacts.htm Accessed March 4, 2009.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2002–2005. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726-1733.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, D.C.: National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2008 [online]. Available at www.nof.org/professionals/NOF_Clinicians_Guide.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2009.

- Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Hopkins R Jr, Forciea MA, Owens DK. Screening for osteoporosis in men: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:680-684.