HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE

Hydroxychloroquine: The Unsteroid?

By Daniel Hal Solomon, MD, MPH Wasko MC, Hubert HB, Lingala VB, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and risk of diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2007;298:187-193.

Abstract

Context: Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), a commonly used anti-rheumatic medication, has hypoglycemic effects and may reduce the risk of diabetes mellitus.

Objective: To determine the association between HCQ use and the incidence of self-reported diabetes in a cohort of patients with RA.

Design, setting, and patients: A prospective, multicenter, observational study of 4,905 adults with RA (1,808 had taken HCQ and 3,097 had never taken HCQ) and no diagnosis or treatment for diabetes in outpatient university-based and community-based rheumatology practices with 21.5 years of follow-up (January 1983 through July 2004).

Main outcome measures: Diabetes by self-report of diagnosis or hypoglycemic medication use.

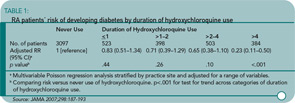

Results: During the observation period, incident diabetes was reported by 54 patients who had taken HCQ and 171 patients who had never taken HCQ, with incidence rates of 5.2 per 1,000 patient-years of observation compared with 8.9 per 1,000 patient-years of observation, respectively (p<.001). In time-varying multivariable analysis with adjustments for possible confounding factors, the hazard ratio for incident diabetes among patients who had taken HCQ was 0.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.42–0.92) compared with those who had not taken HCQ. In Poisson regression, the risk of incident diabetes was significantly reduced with increased duration of HCQ use (p<.001 for trend); among those taking HCQ for more than four years (n=384), the adjusted relative risk (RR) of developing diabetes was 0.23 (95% CI, 0.11–0.50; p<.001), compared with those who had not taken HCQ.

Conclusion: Among patients with RA, use of HCQ is associated with a reduced risk of diabetes.

Commentary

Did you hear the news that a drug for treating lupus and RA may also prevent diabetes? In the past, we have heard about HCQ’s potential to reduce blood cholesterol and act as an anti-platelet agent.1 Add preventing diabetes mellitus to the list. With the rising tide of obesity, a drug that may reduce the diabetes epidemic is welcome news.

Wasko et al. reported that HCQ was associated with a reduced risk of diabetes among RA patients. They studied 4,905 patients with RA enrolled in the ARAMIS cohort. In the current study, the authors examined the onset of diabetes (identified as a new diagnosis or initiating of a new hypoglycemic agent on a semi-annual survey). HCQ use was defined through the semi-annual surveys as well. While duration of HCQ use was assessed, new and ongoing use was not clearly distinguished.

A total of 1,808 (37%) patients reported HCQ use, with a median duration of use of 3.1 years. The rate of new diabetes diagnoses was 5.2 per 1,000 patient-years in the HCQ group and 8.9 per 1,000 in the group not reporting HCQ use. The adjusted reduction in diabetes risk was 38% (95% CI, 8–58%). The multivariable adjusters were broad, including age, gender, race, education, duration of RA, HAQ-DI score, methotrexate, and prednisone use. Moreover, longer exposure was associated with greater risk reduction. (See Table 1, above.)

These results are very provocative and add to a small literature suggesting a hypoglycemic effect of HCQ.2,3 Before we accept these results as truth, the methodologic limitations of this study should be examined. This type of pharmaco-epidemiologic analysis is only as good as the characterization of exposure, definition of endpoint, and control for confounding. The authors have used semi-annual survey reports to assess the exposure. The validity of the patient report of medications and the assumptions regarding medication use between surveys are untested. However, typically, the expected misclassification of exposure biases findings toward the null, not away from the null as observed in this study.

The definition of diabetes is the weakest aspect of the study design. The authors require a patient report of diabetes or new use of a hypoglycemic medication. They state that use of a hypoglycemic agent in subsequent periods was used to “verify” diabetes for patients not reporting medication use at diabetes onset. But less than half of the patients on HCQ with new-onset diabetes reported subsequent use of a hypoglycemic agent. The authors suggest that this observation supports HCQ’s role as a hypoglycemic agent itself; however, I found the definition of diabetes confusing and the fact that so few patients required a specific medication for diabetes was implausible.

Finally, the study’s ability to control for potential confounders was not clear. Glucocorticoid use was assessed, but only represented as a dichotomous variable and not as a continuous cumulative or daily dosage. There was no information about the risk of diabetes associated with glucocorticoid use or any other covariate. It is possible that HCQ’s observed benefits work through a reduction in glucocorticoid cumulative dosage or a substation for another disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug. Also, there was no information about a patient’s level of exercise or family history of diabetes, two potential confounders.

The authors are careful to point out many limitations of their paper. They also appropriately avoid describing the potential relationship between HCQ and diabetes prevention as causal, instead describing an association. This difference is subtle but important, as pharmaco-epidemiology cannot prove causation. This paper should be viewed as hypothesis generating. Proof of this hypothesis will rely on more detailed clinical pharmacologic studies to assess HCQ’s effect on blood sugar. Also, randomized controlled trials of HCQ among patients with borderline blood sugars (with or without RA) should be considered. Until I see these types of data about HCQ, I will not change my prescribing practice. If this association is causal, we will be able to add an important benefit to HCQ’s resume.

References

- Petri M, Lakatta C, Magder L, Goldman D. Effect of prednisone and hydroxychloroquine on coronary artery disease risk factors in systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal data analysis. Am J Med.1994;96:254-259.

- Shojania K, Koehler BE, Elliott T. Hypoglycemia induced by hydroxychloroquine in a type II diabetic treated for polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:195-196.

- Quatraro A, Consoli G, Magno M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in decompensated, treatment-refractory noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A new job for an old drug? Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:678-681.

HCQ Has Many Benefits for Lupus Patients

By Joan M. Von Feldt, MD Alarcon GS, McGwin G, et al. Effects of hydroxychlorquine on the survival of patients with SLE: data from LUMINA a multi-ethnic US cohort (LUMINA L). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1168-1172.

Abstract

Objective: In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), HCQ prevents disease flares and damage accrual and facilitates the response to mycophenolate mofetil in those with renal involvement. A study was undertaken to determine whether HCQ also exerts a protective effect on survival.

Methods: Patients with SLE from the multiethnic LUMINA (LUpus in MInorities: NAture versus nurture) cohort were studied. A case-control study was performed within the context of this cohort in which deceased patients (cases) were matched for disease duration (within six months) with live patients (controls) in a proportion of 3:1. Survival was the outcome of interest. Propensity scores were derived by logistic regression to adjust for confounding by indication as patients with SLE with milder disease manifestations are more likely to be prescribed HCQ. A conditional logistic regression model was used to estimate the risk of death and HCQ use with and without the propensity score as the adjustment variable.

Results: There were 608 patients, of whom 61 had died (cases). HCQ had a protective effect on survival (odds ratio [OR] 0.128 [95% CI, 0.054–0.301] for HCQ alone and OR 0.319 [95% CI, 0.118–0.864] after adding the propensity score). As expected, the propensity score itself was also protective.

Conclusions: HCQ, which overall is well tolerated by patients with SLE, has a protective effect on survival which is evident even after taking into consideration the factors associated with treatment decisions. This information is of importance to all clinicians involved in the care of patients with SLE.

Commentary

This is the second case cohort study published on the beneficial effects of HCQ on survival in SLE and is important in guiding the use of this agent.

The first study, which was published last year by Ruiz-Irastorza et al., presented a prospective cohort of 232 Spanish SLE patients and reviewed the endpoints for thrombosis or death due to any cause.1 In this observational study, 99% of the women were Caucasian and the majority (64%) had received anti-malarials. Taking anti-malarials was protective against thrombosis (HR 0.28, 95% CI, 0.08–0.90) and cumulative 15-year survival rates were lower for lupus patients who had never received anti-malarials than for those who had. A propensity score was used to adjust for confounding variables, including the likelihood that patients treated with anti-malarials would have milder disease and therefore a better outcome.

Dr. Alarcon et al. studied a lupus population that is more typical of what American rheumatologists encounter. The LUMINA cohort is a multiethnic cohort of longitudinally followed patients with SLE. The five-year study presented in this paper was a nested, case-control study where the deceased patients were cases and three randomly chosen live patients were selected for each case. As expected, deceased patients had more severe disease and were more likely to be poor, lack health insurance, and have lower socioeconomic status and lower educational achievement. All of these risk factors have been associated with decreased risk of survival, both individually and together.

A propensity score was utilized to adjust for the confounder that patients treated with HCQ would likely have milder disease and better outcomes than those not treated with HCQ. Applying the propensity score to the multivariate analysis, the protective effect of HCQ on survival remained significant.

In Ruiz-Irastorza et al., only 8% of the cohort was lost to follow-up, whereas in the LUMINA cohort, 36% was lost to follow-up in five years, perhaps reflecting the mobility of U.S. patients. Nevertheless, Dr. Alarcon’s group demonstrated beneficial effects of HCQ on the survival of the remaining cohort. Looking at the causes of death in the LUMINA cohort, there was no difference between the case and control group. This finding is at variance with that of the Spanish group, where no patient treated with anti-malarials died of cardiovascular complications. Similar protective effects were recently reported on behalf of Grupo Latino Americano de Estudio de Lupus at the 2007 PANLAR meeting.

Both studies make a strong case for prescribing HCQ to virtually all SLE patients. Even in patients with more severe disease who require heavy-hitting immunosuppressive agents, HCQ appears beneficial.2 So should HCQ “be in the water” of all SLE patients? Clearly, the evidence seems to indicate that HCQ has substantial and varied effects on health. Furthermore, HCQ appears to be safe in pregnancy and protective against flares during pregnancy.3

The mechanism for HCQ’s protective effect on disease activity and survival is unknown and can be difficult to explain. For my patients, I emphasize that anti-malarials “modulate” the immune system, but may also have anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, anti-hyperlipidemic, and perhaps anti-hyperglycemic effects as well. As with any medication, adverse reactions can occur. The one most frequently screened for is retinal toxicity, but allergic reactions, neuromyopathy, and cardiac complications can also occur. For now, I will continue to advocate the virtues of a relatively cheap medication with few side effects that has long-term beneficial effects for SLE patients.

References

- Ruiz-Irastorza G, Egurbide M-V, Pijoan J-I, et al. Effect of anti-malarials on thrombosis and survival in patients with SLE. Lupus. 2006;15;577-583.

- Kasitanon N, Fine DM, Haas M, Magder LS, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine use predicts complete renal remission within 12 months among patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil therapy for membranous lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2006;15:366-370.

- Clowse ME, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3640-3647.