Opioids are increasingly used to treat chronic pain. They offer a viable option for many patients who either have side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal upset and kidney damage) associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatories (NSAIDs) or are not attaining a level of relief that supports a desirable level of function. In some cases, opioids may be combined with an NSAID or a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) for treatment.

The open-label study reviewed here was conducted with 226 patients from 55 private practices in Germany. All participants had a diagnosis of RA as defined by the ACR criteria. Their initial pain rating was 6 or greater on an 11-point scale; none had been previously treated with transdermal fentanyl, but 38 were taking another opioid. Transdermal fentanyl was started at 25 µg/h in 192 patients (85%), 50 µg/h in 33 patients (14.5%), and 75 µg/h in one patient, and 180 (80%) completed the study protocol.

Patients stopped taking other opiods prior to entering the study but continued other pharmacological (e.g., glucocorticoids, NSAIDs, and methotrexate) and nonpharmacological therapy (e.g., exercise).

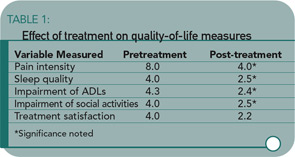

The study results showed significant improvement in pain intensity, sleep quality, activities, treatment satisfaction, and perceived general well-being. All variables other than pain intensity were measured on 5-point scales. (See Table 1)

There were a total of 75 adverse events in 39 (17%) of the patients. The most common were nausea (22%) and vomiting (16%). Few (1.3%) experienced constipation, which is generally acknowledged as an issue related to the use of opioids.2

About half of the sample (58%) agreed to be contacted at the end of six and 12 months to determine whether the initial study findings remained stable. The mean dose of fentanyl for this subgroup had increased from 28.8 µg/h at the end of 30 days to 49.1 µg/h at the end of 12 months. With this moderate increase in dose, all of the findings remained stable.

The study’s findings do indicate that transdermal fentanyl might be given consideration for pain management, as well as management of other symptoms (e.g., sleep quality and function) and of overall quality of life (e.g., coping with daily demands and feeling content). This is in keeping with the American Pain Society’s recommendation that “Opioids should be used for patients with OA and RA when other medications and nonpharmacologic interventions produce inadequate pain relief and the patient’s quality of life is affected by the pain.”2