LUPUS

Rituximab for Neuropsychiatric Lupus

By Robyn Domsic, MD

Tokunaga M, Saito K, Daisuke Kawabata D, et al. Efficacy of rituximab (anti-CD20) for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus involving the central nervous system. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):470-475.

Abstract

Aim: Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) is a serious treatment-resistant phenotype of systemic lupus erythematosus. A standard treatment for NPSLE is not available. This report describes the clinical and laboratory tests of 10 patients with NPSLE before and after rituximab treatment, including changes in lymphocyte phenotypes.

Methods: Rituximab was administered at different doses in 10 patients with refractory NPSLE, despite intensive treatment.

Results: Treatment with rituximab resulted in rapid improvement of central nervous system (CNS)–related manifestations, particularly acute confusional state. Rituximab also improved cognitive dysfunction, psychosis, and seizure, and reduced the SLE Disease Activity Index Score at day 28 in all 10 patients. These effects lasted for more than one year in five patients. Flow cytometric analysis showed that rituximab down-regulated CD40 and CD80 on B cells and CD40L, CD69, and inducible costimulator on CD4+ T cells.

Conclusions: Rituximab rapidly improved refractory NPSLE, as evident by resolution of various clinical signs and symptoms and improvement of radiographic findings. The down-regulation of functional molecules on B and T cells suggests that rituximab modulates the interaction of activated B and T cells through costimulatory molecules. These results warrant further analysis of rituximab as treatment for NPSLE.

Commentary

This study is the first case series reporting the outcomes with rituximab for CNS manifestations of lupus. Prior series have included patients with CNS involvement as one of their lupus manifestations, but improvement in CNS symptoms has not been the focus of these studies and received little more than a few sentences in the discussion. Interestingly, this article received the fourth highest number of hits in the month of April on the Annals of Rheumatic Disease Web site. This is not surprising since the use of rituximab in the treatment of rheumatic disease, particularly lupus, is a hot topic.

From the abstract, the study sounded convincing and I was excited about the use of rituximab for CNS lupus. Once I delved into the methods section, however, concerns began to arise. Allow me to review the inclusion criteria of the study: 1) highly active disease and 2) CNS lesions resistant to conventional treatment. If the latter criterion is strictly followed, then it is not clear how one individual with a headache and normal MRI and a second with mood disorder and a normal MRI qualify as two of the ten patients.

Another of my concerns relates to standardization to the treatment regimen. In fact, there were four different regimens of rituximab given, and seven steroid treatments (consisting of three preparations) at the time of study entry. Whether these differences influenced outcome is unknown, although a more uniform regimen would have simplified interpretation of the study. With respect to laboratory studies, the assessment appears to be extensive and includes the IgG index and IL-6 from cerebrospinal fluid, MRI, SPECT scan, and FTG–positron emission tomography. The analysis of costimulatory molecule expression also appears complete, with a reduction in functional molecule expression on B and T cells reported. From these findings, the authors suggest that rituximab may work by modulating B and T cell interaction via these molecules.

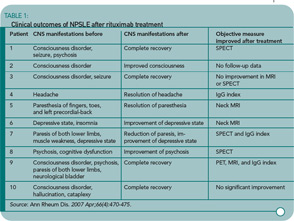

Despite the methodologic concerns I have noted, the study is important because it reports all 10 patients experienced clinical improvement, with six experiencing some radiologic improvement in at least one reported modality. (See Table 1) The results are certainly intriguing. However, because of the manner in which results are reported and the differences in the treatment regimens, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the value of rituximab in this setting. For now, I think I’ll keep rituximab in my back pocket for my patients with CNS lupus who are either unable to tolerate or in whom I would like to minimize use of other cytotoxic therapies, and in those patients not responding to more traditional therapies.

Clearly, the rheumatology community needs a well-conceived and -executed study to examine the clinical effects of rituximab for lupus CNS manifestations. I hope that either a large center or group of centers take on this challenge and provide a prospective study with well-defined patient groups, standardized imaging protocols, pre-defined follow-up criteria, and a control group. One possible protocol could randomize patients with severe CNS manifestations (seizures, coma, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis) to pulse steroids plus IV cytoxan therapy versus pulse steroids plus rituximab. Immunologic studies could also be performed so that we gain knowledge not only on clinical outcomes, but immunologic mechanisms and effects of this drug in lupus patients.

BACK PAIN

Timing of Herniated Disc Surgery

By David G. Borenstein, MD

Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2245-2256.

Abstract

Background: Lumbar-disk surgery often is performed in patients who have sciatica that does not resolve within six weeks, but the optimal timing of surgery is not known.

Methods: We randomly assigned 283 patients who had had severe sciatica for six to 12 weeks to early surgery or to prolonged conservative treatment with surgery if needed. The primary outcomes were the score on the Roland Disability Questionnaire, the score on the visual-analogue scale for leg pain, and the patient’s report of perceived recovery during the first year after randomization. Repeated-measures analysis according to the intention-to-treat principle was used to estimate the outcome curves for both groups.

Results: Of 141 patients assigned to undergo early surgery, 125 (89%) underwent microdiscectomy after a mean of 2.2 weeks. Of 142 patients designated for conservative treatment, 55 (39%) were treated surgically after a mean of 18.7 weeks. There was no significant overall difference in disability scores during the first year (p=0.13). Relief of leg pain was faster for patients assigned to early surgery (p<0.001). Patients assigned to early surgery also reported a faster rate of perceived recovery (hazard ratio 1.97; 95% confidence interval 1.72 to 2.22; p<0.001). In both groups, however, the probability of perceived recovery after one year of follow-up was 95%.

Conclusions:

The one-year outcomes were similar for patients assigned to early surgery and those assigned to conservative treatment with eventual surgery if needed, but the rates of pain relief and of perceived recovery were faster for those assigned to early surgery.

Commentary

The patient with leg pain associated with a herniated intervertebral disc faces a number of treatment options. A herniated disc may heal spontaneously over a time period measured in months. Medical therapy including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, oral and/or injectable corticosteroids, and physical therapy can ease pain and decrease inflammation of damaged tissues during this time of disc resorption. Surgical intervention removes the offending piece of herniated nucleus pulposus with almost immediate resolution of leg pain. When patients are offered all of these options, the question frequently asked by those considering surgery is, What is the timeframe for a good outcome from an operation? The commonly quoted dictum is that surgery needs to be undertaken within 12 weeks of the onset of sciatica to have the best result.1 Peul and co-workers would disagree and state that the window of opportunity for a successful surgical outcome is six months or longer.

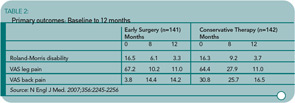

In the Peul study, one cohort of patients who had not improved between six to 12 weeks after a disc herniation underwent surgery within two weeks of evaluation (early surgery group). Patients who were assigned to conservative therapy could opt for surgery if they had no improvement. The average time for the 40% of medically treated patients who went on to surgery was 4.5 months. The one-year outcomes of the entire surgical and conservative treatment groups were similar. The difference was the earlier resolution of disability and pain in the surgical cohort. (See Table 2)

Do the results of this study apply to all patients with sciatica related to a disc herniation? The patients excluded from the study would suggest no. Individuals with cauda equina syndrome or severe muscle weakness were excluded because of the need for immediate surgical decompression. Patients who had a prior disc herniation, prior spine surgery, pregnancy, or severe coexisting disease were not eligible. Therefore, this study applies to young, healthy individuals with sciatica associated with their first disc herniation.

Another of my concerns is the absence of a standardized approach to medical therapy. The conservative treatment subjects were prescribed activities as tolerated, pain medications, and physiotherapy visits in any combination. The absence of guidelines for medical therapy remains a major failing of studies designed by spine surgeons.2 Of interest, the surgical technique for discectomy is described in greater detail. My point is that conservative medical therapy outcomes could be better than what is described in this paper.

Overall, patients with sciatica from a herniated disc should be encouraged by this study. At the end of a year, they should experience minimal disability and have residual pain of 1 or less on a visual analogue pain scale (VAS) independent of their choice of therapy. Surgery can be delayed for months and can still offer rapid relief of symptoms for those with persistent intractable pain who do not resolve in the usual time course.

References

- Postachinni F. Results of surgery compared with conservative management for lumbar disc herniations. Spine. 1996;1383-1387.

- Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs. nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA. 2006;296:2451-2459.