Prognostic Factors in Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

By Robyn T. Domsic, MD

Bronner IM, van der Meulen MFG, de Visser M, et al. Long-term outcome in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Nov;65(11):1456-1461.

Abstract

Background: Although polymyositis and dermatomyositis are regarded as treatable disorders, prognosis is not well known, because long-term outcome and prognostic factors vary widely in the literature.

Aim: To analyze the prognostic outcome factors in polymyositis and adult dermatomyositis.

Methods: The authors determined mortality, clinical outcome (muscle strength, disability, persistent use of drugs, and quality of life), and disease course and analyzed prognostic outcome factors.

Results: Disease-related death occurred in at least 10% of the patients, mainly because of associated cancer and pulmonary complications. Re-examination of 110 patients after a median follow-up of five years showed that 20% remained in remission and were off drugs, whereas 80% had a polycyclic or chronic continuous course. The cumulative risk of incident connective tissue disorder in patients with myositis was significantly increased. Sixty-five percent of the patients had normal strength at follow-up, 34% had no or slight disability, and 16% had normal physical sickness impact profile scores. Muscle weakness was associated with higher age (odds ratio [OR] 3.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3 to 10.3). Disability was associated with male sex (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.2 to 7.9). Forty-one percent of the patients with a favorable clinical outcome were still using drugs. Jo-1 antibodies predicted the persistent use of drugs (OR 4.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 15.0).

Conclusions: Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are serious diseases with a disease-related mortality of at least 10%. In the long term, myositis has a major effect on perceived disability and quality of life, despite the regained muscle strength.

Commentary

Several retrospective studies in the last 30 years have addressed the prognosis of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. From these studies, certain trends are notable: a sizable mortality rate ranging from 5% to more than 50%, with the highest mortality in those with malignancy; a chronic continuous disease course in the majority of cases; high levels of subsequent disability; and association of poor outcomes with several factors (older age, presence of interstitial lung disease, esophageal dysfunction, respiratory muscle weakness, or cardiac involvement). While early studies likely included patients with inclusion body myositis (IBM), subsequent studies are more cognizant of the importance of distinguishing IBM from polymyositis. However, diagnostic uncertainty remains.

Bronner and colleagues attempt to address the dilemma of prognosis in myositis by asking two questions. The first question is whether polymyositis and dermatomyositis are associated with different prognosis. The second question is whether the presence of specific autoantibodies affects the clinical course.

The major strengths of the study are the rigor applied to excluding IBM and the efforts expended to both diagnose and distinguish between dermatomyositis and polymyositis utilizing muscle biopsy, clinical features, and autoantibody analysis. There is sufficient follow-up (only 13% not evaluated at follow-up). This study reflects a tremendous amount of work and effort, although it is retrospective in design and the classification of myositis disease subsets (although previously published) has not been subjected to critical analysis.

In this study, the prognostic factors assessed were age at onset of disease, gender, myositis classification, time to treatment, and presence of myositis-specific autoantibodies. There is a notable absence of organ system involvement among factors evaluated.

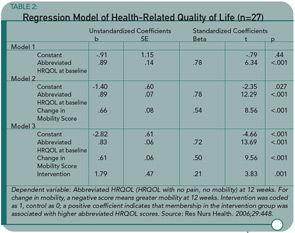

This study confirms that 1) polymyositis and dermatomyositis are serious diseases with a significant mortality rate (>10%) that is highest among those individuals with an underlying malignancy; 2) most myositis patients experience a chronic, continuous disease course (see Table 1), and 3) patients subsequently report high rates of disability and a low quality of life.

The finding that disease classification by muscle biopsy and autoantibody doesn’t affect prognosis is surprising and provocative. However, for me, there are a number of questions still unanswered. I’d like to see this study reanalyzed to include an evaluation of organ involvement (even if it is done retrospectively). Or, better yet, I would like to see a larger cohort study utilizing muscle biopsy, autoantibody, and organ system involvement while adjusting for treatment. If either of these analyses is done, I think the results could affect management of patients with inflammatory myopathy. Identification of true prognostic factors could enable us to identify patients at risk for a poor outcome and consider aggressive treatment to include immunosuppressive agents early in the disease course for these individuals. This would be a true step forward and allow us to begin limiting the mortality and disability from this disease.

Guided Imagery with Relaxation Can Decrease Disability in OA

By Gail C. Davis, RN, EdD

Baird CL, Sands LP. Effect of guided imagery with relaxation on health-related quality of life in older women with osteoarthritis. Res Nurs Health. 2006; 29:442-451.

Abstract

OA is the most common cause of disability in older adults, which, in turn, leads to poor quality of life (QOL). Disability is caused primarily by the joint degeneration and pain associated with OA. A randomized pilot study was conducted to test the effectiveness of guided imagery with relaxation (GIR) to improve health-related QOL (HRQOL) in women with OA. A two-group (intervention versus control) longitudinal design was used to determine whether GIR leads to better HRQOL in these individuals and whether improvement in HRQOL could be attributed to intervention-associated improvements in pain and mobility. Twenty-eight women were randomized to either the GIR intervention or the control intervention group. Using GIR for 12 weeks significantly increased women’s HRQOL in comparison to women who used the control intervention, even after statistically adjusting for changes in pain and mobility. These findings suggest that the effects of GIR on HRQOL are not limited to improvements in pain and mobility. GIR may be an easy-to-use self-management intervention to improve the QOL of older adults with OA.

Commentary

The changes that occur with aging affect both the medications and amount of medication that can be tolerated by older adults, putting them at higher risk for adverse effects. Pharmacokinetic responses, like decreased renal excretion of drugs and changes in drug absorption, and issues related to possible drug interactions and the effects of drugs on the gastrointestinal system present important considerations for the older adult’s management of chronic pain and related QOL. These issues emphasize the importance of this study that tests a non-pharmacological approach, not frequently used by older adults, for improving QOL.

This study was conducted to add to the knowledge about a modulation technique that combines guided imagery and relaxation (GIR) to improve QOL. Older adults who live with OA and chronic pain know that a variety of management methods, such as guided imagery with relaxation and exercise, are needed to modulate pain over time. Unfortunately, though, many patients have not been introduced to these approaches and how to use them effectively. It’s not unusual to hear persons say, “I don’t want to take more medicine for pain—it makes me feel worse,” when “worse” refers to such side effects as dizziness, clouded thinking, and gastrointestinal problems.

The authors acknowledge that pain and mobility are important physical HRQOL issues for older women with OA, but that HRQOL is influenced by psychological and social factors as well. Experimental and control groups were used to determine the effect of GIR on HRQOL from a comprehensive point of view. An interesting twist of this study was its attempted to determine whether an abbreviated HRQOL that didn’t include measures of pain and mobility was affected by the GIR intervention, and whether changes in pain and mobility were significantly associated with the abbreviated HRQOL score.

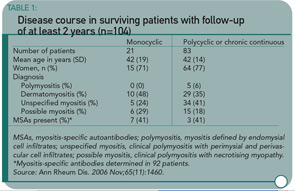

The total score of the AIMS2 was used as the measure of HRQOL; the pain and mobility scale scores were removed for the abbreviated HRQOL score. All 17 women (M age = 72.06 years) in the intervention group showed significant improvement on both total and abbreviated HRQOL scores, while the 10 in the control group (M age = 74.8 years) did not. This last question was addressed using a stepwise regression analysis that included three models. (See Table 2) Model 3 includes all of the significant independent variables of interest; the change in the pain score was not significant.

An encouraging and clinically useful finding of this study is that GIR provides an effective modulation method that older women with OA can use to improve their HRQOL. It is a self-management strategy that is easy to teach and easy to use. Women in this study used it twice a day. A value in initially having it prescribed a certain number of times is that practicing it successfully could lead to more frequent use. How helpful it would be if used on demand, as when pain or emotional stress increase, rather than a prescribed number of times, is a necessary follow-up question.

I found the last study question in Table 2 less relevant to clinical practice. That a change in pain did not influence the abbreviated HRQOL was not surprising because effective pain management has more to do with how individuals deal with pain (which might be viewed as QOL) than whether they are able to reduce it, and the intensity of chronic pain varies over time. I wonder why the mobility and function scales were not all removed to form an abbreviated AIMS2 focusing on mood and psychosocial factors. Given the measures used, it also isn’t surprising that a change in mobility influenced the abbreviated QOL that included function. I would be interested to know if mood and psychosocial factors, as an abbreviated scale, were influenced by a change in mobility and function. Even with these remaining questions, I believe the study results lend strong support for teaching persons with OA to use GIR to improve QOL.

New Mouse Model for RA

By Mary Corr, MD

Kawane K, Ohtani M, Miwa K, et al. Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature. 2006 Oct 26;443(7114):998-1002.

Abstract

A large amount of chromosomal DNA is degraded during programmed cell death and definitive erythropoiesis. DNase II is an enzyme that digests the chromosomal DNA of apoptotic cells and nuclei expelled from erythroid precursor cells after macrophages have engulfed them. Here we show that DNase II-/-IFN-IR-/- mice and mice with an induced deletion of the DNase II gene develop a chronic polyarthritis resembling human RA. A set of cytokine genes was strongly activated in the affected joints of these mice, and their serum contained high levels of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, rheumatoid factor, and matrix metalloproteinase-3. Early in the pathogenesis, expression of the gene encoding tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a was upregulated in the bone marrow, and administration of anti–TNF-a antibody prevented the development of arthritis. These results indicate that if macrophages cannot degrade mammalian DNA from erythroid precursors and apoptotic cells, they produce TNF-a, which activates synovial cells to produce various cytokines, leading to the development of chronic polyarthritis.

Commentary

A new model of murine arthritis involves aberrant macrophage degradation of engulfed DNA. The appropriate handling and removal of DNA-protein complexes from sites of rapid cell turnover or cell death is quintessential for healthy tissue homeostasis. Several nucleases are responsible for removing DNA from nuclear antigens, and disrupted clearance of nuclear DNA complexes may initiate and perpetuate autoimmune disease. Indeed, mice deficient in DNase 1, the major nuclease present in serum and urine, develop anti-nuclear antibodies, deposition of immune complexes in glomeruli, and full-blown glomerulonephritis. However, Kawane and colleagues report a different phenotype in mice with an induced deletion of DNase II. DNase II is an enzyme largely expressed by macrophages that digest the chromosomal DNA of phagocytosed nuclei or nuclear material from apoptotic cells and erythroid precursor cells. DNase II-/- mice develop a lethal anemia unless they are intercrossed with mice deficient for the type I interferon receptor (IFN-IR). The doubly deficient DNase II-/-IFN-IR-/- mice survive into adulthood, but develop a robust chronic polyarticular arthritis.

The inflammation in the joints of these mice encompasses both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms. The DNase II-/-IFN-IR-/- mice have anti-dsDNA antibodies, and their sera contain high levels of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor. These mice did develop anti-dsDNA antibodies despite their inability to respond to IFN-I; however, the arthritis-associated antibodies are presumably involved in the dominant phenotype. In collagen-induced arthritis, IFNb ameliorates disease. The inability of DNase II-/-IFN-IR-/- mice to respond to type I interferon is not the cause of joint inflammation as the same phenotype occurs in mice with a postnatally induced deletion of DNase II that requires an IFN-I response to maintain.

In this model, the underlying inflammatory process is more systemic than local synovitis. Early in the disease course, macrophages laden with undigested lysosomal nuclear material produce TNF-a in the bone marrow. Intervention with anti–TNF-a antibodies clinically suppresses disease even at a time point when circulating autoantibodies are likely to be present. The mechanism whereby the excess load of DNA causes the macrophages to release TNF remains unclear. TNF-a release by DNase II deficient macrophages was previously shown to be independent of Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling. In addition, deletion of DNA-sensing TLR-9 in DNase II-/-IFN-IR-/- had no effect on the development of arthritis.

This report provides a new mouse model for the development of disease and how macrophages may contribute to disease, independently yet in concert, with T and B cells. Most recent work in models with DNase and IFN-1 has focused on their roles in the development and progression of SLE; however, the unexpected phenotype of a inflammatory arthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis suggests that macrophages elaborating TNF-a early in the disease process may be pivotal in the skewing the later manifestations and disease profile.