A number of autoinflammatory syndromes that result from genetic mutations have been described recently. The vast majority occur in children. However, three periodic fever syndromes are important for rheumatologists who treat adults to know about. The goal of this review is to provide a concise description of each condition, and to help the clinician understand when to suspect one and how to diagnose it.

Adult Still’s Disease

The first of these periodic fever syndromes is Still’s disease, first described by George Frederic Still in 1897 at the Great Ormand Street Hospital in the Bloomsbury neighborhood in London. His treatise, “On a Form of Chronic Joint Disease in Children,” described 22 patients with what is now seen as the classic triad of fever, rash and joint pain.

E.G.L. Bywaters, the first to describe the syndrome in adults, was an Englishman trained in rheumatology by the legendary Walter Bauer, MD. at the Massachusetts General Hospital. When World War II broke out, Dr. Bywaters returned to England. During the bombing of London, he discovered that renal failure in crush syndrome resulted from the release of myoglobin. In 1971, he went on to describe 14 adults with a presentation similar to that described by Still, and this syndrome came to be known as adult Still’s disease (AOSD).

A daily (quotidian) fever is characteristic of AOSD and is sometimes described as a picket fence fever, spiking in the afternoon or early evening, then returning to normal. This occurs in up to 80% of AOSD patients, tends to last around four hours and often precedes the development of other manifestations. Severe supparative pharyngitis sometimes precedes fever or rash.

Figure 1

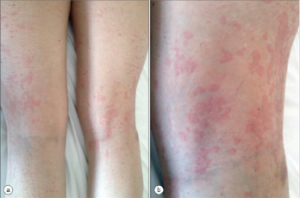

AOSD Rash

The rash also has characteristic features: macular or maculopapular, nonpruritic, evanescent, and of a faint salmon or pinkish color vessels (see Figure 1). It tends to occur with the fever and may be brought on by a hot shower. (My mentor called it the intern’s rash, because the intern was the only doctor in the hospital in the evening when the rash occurs.) The rash exhibits the Koebner phenomenon, which means that it can be brought on by mild trauma. (Heinrich Koebner, MD, described this in psoriasis patients. He was better known for inoculating his arms with three different fungi to demonstrate the infectious nature of the rashes they caused). Stroking the skin with the finger will sometimes provoke the rash (I like to draw an S), and examination of the upper back will often reveal pink lines that correspond to the creases in the bed sheets. Pathologically, the findings are nondiagnostic: dermal edema, perivascular inflammation in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes and histiocytes, with C3 deposition in the blood.

Both arthralgias and frank arthritis can occur. Initially, these tend to be transient and mild in an oligoarticular distribution: knees, wrists, ankles, elbows, shoulders and PIP joints. However, these conditions may evolve over months to a severe and destructive polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. Radiographic evidence of wrist fusion is very characteristic, but rare (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wrist Fusion

In addition to the classical triad of fever, rash and joint pain, a variety of gastrointestinal manifestations can occur. Abdominal pain occurs in up to half of patients, and nausea, anorexia and weight loss can occur. More serious problems include aseptic peritonitis, acute pancreatitis and lymphadenitis. Hepatomegaly can occur, and modest elevations of transaminases are common. Eight cases of fulminant liver failure have occurred, with four fatalities. Splenomegaly occurs in up to half of patients, as does cervical lymphadenopathy.

Cough, dyspnea and pleurisy can occur. Pleural effusions, pericarditis, myocarditis, arrhythmias, tamponade and interstitial pulmonary infiltrates may occur. The adult respiratory distress syndrome can occur in the setting of the macrophage activation syndrome. Aseptic meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia can occur.

The macrophage activation syndrome (i.e., hemophagocytic syndrome) was reported in 12% of 50 patients.1 This presents with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, very high serum triglycerides, and normal or low haptoglobin and fibrinogen. A bone marrow exam shows hematopoietic cells undergoing phagocytosis by macrophages.

Disease course can be quite variable, not only in severity, but in terms of pattern. A monophasic pattern, with fever, rash, serositis and hepatosplenomegaly, runs a course of weeks to months, usually resolving within a year. An intermittent pattern entails remissions and exacerbations over months to years. Subsequent flares tend to be shorter and less severe. Finally, the chronic pattern involves persistently active disease with articular symptoms and, sometimes, destructive arthritis.

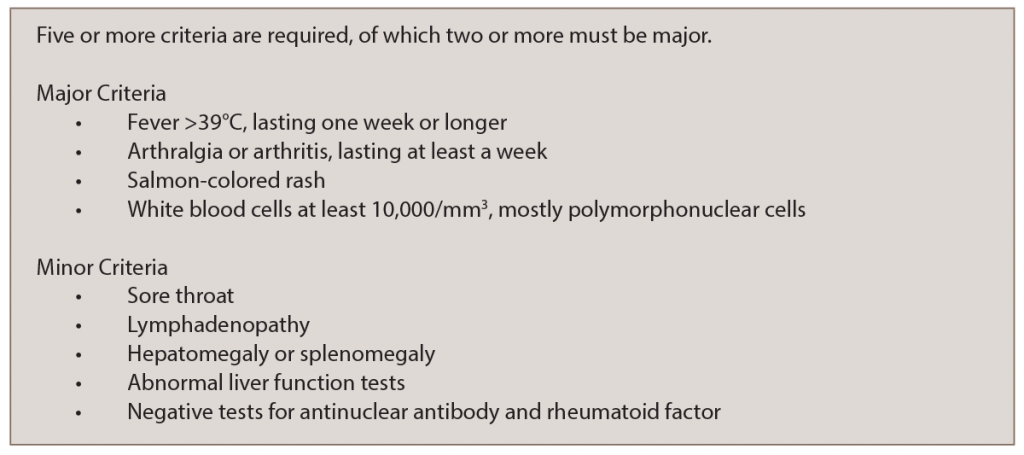

AOSD is a clinical diagnosis, which requires exclusion of infectious and malignant causes of fever. The Yamaguchi Criteria (see Table 1) are met by the presence of five criteria, of which two must be major.2 However, such criteria are not absolute, and in the end, it is the clinical judgment of the physician that establishes the diagnosis.

The pathophysiology of ADS is obscure. It has been hypothesized to be a reactive process to an infection (like many other rheumatologic diseases). Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 2 (IL-2), interferon gamma (IFN and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), are present in substantial amounts: biologic DMARDs targeting TNFα and other cytokines are sometimes effective treatments.

Autoimmune vs. Autoinflammatory Diseases

Rheumatologists are familiar with autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren’s syndrome, etc., which are mediated by T and B cells of the adaptive immune system. A vaccination produces a reaction from the adaptive immune system to produce protective antibodies. Autoantibodies are associated with autoimmune diseases in many cases.

By contrast, what have come to be known as the autoinflammatory diseases entail a seemingly unprovoked inflammatory response with no autoantibodies from the innate immune system. This is the primitive arm of the immune system that reacts immediately to patterns (such as LPS, or monosodium urate crystals). Acute gouty arthritis can be viewed as an autoinflammatory disorder, in which recognition of urate by toll-like receptors leads to activation of the inflammasome, resulting in an explosive production of IL-1, and intense inflammation with the classic findings of calor, dolor, rubor and tumor, the heat, redness and swelling, which we see with acute gouty arthritis.

A number of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases have been characterized mostly in children. Is AOSD an autoinflammatory disease? The genetic basis and molecular pathology have not been characterized to the same degree as TNF‑receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) or familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). Yet for the purpose of this discussion, I am going to include AOSD in this group.

FMF

Familial Mediterranean fever is the monogenic autoinflammatory disease that adult rheumatologists are most likely to see. First described in 1908, it was named FMF in 1958. The MEFV (Mediterranean fever) gene, which was cloned in 1997, has an autosomal recessive mutation of pyrin.

Recurrent episodes of fever and serosal inflammation occur before the age of 20 years in 90% of patients, and most attacks begin in early childhood. However, in rare cases the first attack can occur after the age of 50. The febrile episodes have an abrupt onset, typically last one to three days and can resolve spontaneously. Only rarely can a precipitating event be identified: exercise, cold, emotional stress, fatigue, surgery or menses. Patients are asymptomatic between attacks, and the interval between attacks can be highly variable: a week to years.

In addition to fever, numerous other problems can occur. Abdominal pain occurs in 95% of patients. It tends to be localized initially, then more generalized, with features of guarding, rebound, rigidity and ileus. It may mimic a surgical abdomen, such as appendicitis. The mechanism is infiltration of neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity causing serositis.

Arthralgia and arthritis occur in about three-fourths of patients. Most commonly, this is monoarticular or polyarticular in large joints, with a migratory pattern being rare. This may be precipitated by trauma and prolonged walking. Sterile synovial fluid is found when joints are aspirated. Although this gradually resolves in 24–48 hours, a chronic/destructive arthritis may develop (rarely).

Chest pain occurs in about half of patients. This tends to be pleuritic, with subdiaphragmatic inflammation, and a small pleural effusion may be found. Pericarditis is rare. Like other manifestations, this tends to resolve in three to seven days.

Rare manifestations include orchitis, myalgia or aseptic meningitis. Polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s and Henoch-Schonlein purpura occur with an increased incidence.

Quite a bit is known about the genetics of FMF, because there are a number of mutations of the MEFV gene. No null mutations have been identified. Two-thirds of patients actually have multiple mutations, which may result in gain or loss of function.

The MEFV gene is on the short arm of chromosome 16 and encodes pyrin, a 781 amino acid protein found in the cytoskeleton of neutrophils, synovial fibroblast, and dendritic cells. Pyrin is a major regulator of the inflammasome, a complex of proteins that trigger the release of IL-1 beta.

The most frequent mutation is M694V, which has a prevalence of 20–65%. Patients with M694V have the most severe phenotype, with arthritis, high fever, splenomelagy, more frequent attacks and a higher frequency of amyloidosis. M694V is found particularly in North African Jews.

Five mutations account for 75% of cases in Armenians, Arabs and Turks. One of these, E148Q, tends have a milder phenotype, with milder disease and less frequent attacks. This mutation has reduced penetrance.

The most dreaded complication of FMF is secondary amyloidosis, with deposition in the kidney, spleen, liver, heart, thyroid, testis and GI tract. Proteinuria, sometimes in the nephrotic range, can be followed by end stage renal disease from two to 13 years later.

Fortunately, most patients with FMF respond to colchicine. In fact, some experts argue that failure to respond to colchicine excludes the diagnosis of FMF. Ninety-five percent of patients improve, 75% with near remission. Presumably, colchicine’s mechanism of action is inhibiting cytokine production, especially IL-1, by the inflammasome. Colchicine may even have some efficacy in the prevention of amyloidosis.

A daily (quotidian) fever is characteristic of AOSD & is sometimes described as a picket fence fever, spiking in the afternoon or early evening, then returning to normal.

TRAPS

The third autoinflammatory syndrome that may present in adults is TRAPS, formerly known as Familial Hibernian fever. These febrile episodes last longer than in FMF or AOSD, up to two weeks in duration, and may occur every five to six weeks.

Most develop TRAPS in the first decade of life, but 10% present after the age of 30 years. This is the rarest of the three periodic syndromes, with a prevalence of about one in a million.

Attacks of fever can be accompanied by arthritis, serositis and rash. The rash presents with single or multiple patches, which spread distally down the extremities. Biopsy shows superficial and deep infiltration by lymphocytes and monocytes. Conjunctivitis and periorbital edema occur. About 15% of patients develop amyloidosis, especially with mutations that replace cysteine, because these are important in the intramolecular disulfide bonds that maintain the three-dimensional structure of TNF1.

TRAPS is caused by autosomal mutations with incomplete penetrance in the TNFRSF1A gene encoding the 55 kd TNF receptor (TNFR1). Sometimes this mutation results in impaired shedding of the TNFR1, which could diminish its antagonistic effects on TNF. Another possibility is that excess of retained surface TNFR1 could result in excess binding of TNF. A mutant receptor may bind TNF less efficiently, resulting in less TNF-

associated apoptosis. A more indirect effect of the mutation might result in misfolding of TNF1, triggering the unfolded protein response, a cellular stress response associated with the endoplasmic reticulum. Finally, this misfolded protein may initiate signaling within the cell, mediated by mitochondrial derived reactive oxygen species, which disturb intracellular signaling.

Unlike FMF, TRAPS does not respond to colchicine. Corticosteroids help, but often long courses of high doses are required. It seems obvious that etanercept would help by binding excess TNF. However, the IL-1 antagonists anakinra and canukinumab may also be effective. These biologic agents may help reduce the extent of amyloidosis.

Conclusion

In summary, three different autoinflammatory syndromes may present during, or persist into, adulthood. Recognizing their characteristic features is essential to making the right diagnosis.

- Patients with AOSD, which more commonly presents in adulthood, have daily fevers that spike in the late afternoon or evening. The fevers are associated with the presence of the characteristic rash. Typically, the temperature returns to the normal range.

- FMF usually presents in childhood, with a fever that can last for one to three days without returning to normal. Abdominal pain with the febrile episodes is common. FMF almost always responds to colchicine.

- The fever in TRAPS may last up to two weeks; periorbital edema and the rash are unlike what is seen in AOSD.

Rick Brasington, MD, is a rheumatologist and fellowship program director at Washington University in St. Louis, as well as an associate editor of The Rheumatologist.

Rick Brasington, MD, is a rheumatologist and fellowship program director at Washington University in St. Louis, as well as an associate editor of The Rheumatologist.

References

- Arlet JB, Le TH, Marinho A, et al. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still’s disease: A report of six patients and a review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Dec;65(1):1596–1601.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar;19(3):424–430.