Some argue, however, that focusing on the individual may be prioritizing expediency over efficacy. Christine Sinsky, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association, notes that “to start with individual changes is like telling the canary in the coal mine that he should just try harder.”17 The sea change that has taken place over the past several years is the recognition that burnout is an organizational problem that requires an organizational approach.

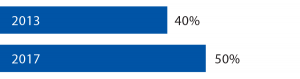

Percentage of Physicians Who Reported Symptoms of Burnout6,7

The American Medical Association defined the triple aim of healthcare as lower costs, better outcomes and improved patient cares. More recently, the American Medical Association has updated this to include a fourth aim: clinician well-being. To promote this latest aim, the American Medical Association has created the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine, which serves as a resource for hospitals, medical centers and other organizations to promote clinician wellness. The organization also provides resources to help prove to administrators that promoting clinician wellness makes good financial sense. The foundation argues that “a more engaged, satisfied workforce will provide better, safer, more compassionate care to patients, which will, in turn, reduce the costs of care.”11

The argument is compelling. Every year, 7% of physicians will withdraw from providing clinical care because of burnout. Nationwide, it costs, on average, half a million dollars to recruit and train a physician to replace one who has left the workforce.11 With this in mind, the cost of initiatives to support clinician wellness start to seem like a pittance.

The importance of addressing burnout in the workplace seems like a no-brainer, so much so that the American Medical Association has trademarked the phrase Joy in Medicine, perhaps expecting that this will be the great advance in medicine for our generation. I certainly hope so. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the American College of Surgeons and other professional organizations all agree that burnout must be addressed urgently, and many institutions have followed suit, with public initiatives to put the joy back in medicine.

There’s the rub. It is easy to agree that burnout must be addressed at an institutional level, harder to institute the necessary changes and harder still to make physicians feel that substantial changes have taken place. When asked what his institution was doing to address burnout, one participant in a New England Journal of Medicine-sponsored survey responded curtly: “Not enough.” Other responses included the phrases, “lip service,” “administrative denial” and “talking about the problem in committees but no action plan yet.”18