Rates of burnout and depression are substantially higher among physicians than they are among the general population.

David Mack / Science Source

4 Patients in 4 Weeks

Baltimore is a little over two hours away from Richmond, Va., by car. I know this now because I recently drove to Richmond to attend a memorial service.

I drove in silence. Music made me sleepy, and I could not bear to listen to another iteration of how we are narrowly escaping disaster in any number of geopolitical areas, so I turned the radio off. In the quiet, it occurred to me that she was the fourth patient I had lost in four weeks. I hope not to best that record any time soon.

Two were patients I had cared for while attending on our inpatient consult service. They were, therefore, not “mine” in the way that physicians think of ownership. The first was a patient with interstitial lung disease who presented with either progressive fibrosis or an opportunistic infection—we still don’t know the root cause of his decline. When I met him, I really did not understand why my colleagues in pulmonary medicine were not more sanguine; he was ill, but he was in good spirits and was well enough to crack jokes about how the hospitalization had conveniently gotten him out of his wife’s annual pilgrimage to Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. A week later, I had started to see what my colleagues had already seen, and I watched, helpless, as he slowly suffocated to death.

The second patient had recently been diagnosed by a colleague as having scleroderma. For some patients, this might mean cold fingers and a touch of indigestion. For this patient, the disease spread through her body like wildfire, within months encasing her skin and her gut in unyielding fibrosis. The latter was the real problem; her daughter reported that everything—medications, food—sat in her stomach for hours, unmoving. There is a short window of opportunity during which a patient may leave the hospital, unscathed by our good intentions. This patient missed that window, and despite her unusual diagnosis, the cause of her death was rather mundane. If I am being honest, the situation was more complicated than that: The patient never really adjusted to her diagnosis of scleroderma and was deeply, profoundly depressed. If I were reviewing her hospitalization objectively, I could state the cause of death with great certainty; having been there at the time, I can’t help but wonder if she died of a broken heart.

The third patient was mine, and her passing cut more deeply. Years ago, she taught me that microscopic polyangiitis does not recur, except when it does. I distinctly remember calling her from my hotel room in Chicago, starting in a reasonable voice, but eventually shouting into my cell phone that she needed to go to the hospital now because she was developing the first signs of glomerulonephritis.

After years of having quiescent disease, however, she was unconvinced. She told me about her weekend plans, which included a birthday party that she was looking forward to, and she stated, firmly, that she would go to the hospital on Monday, after her personal obligations had passed.

I should not have been surprised. You could always tell when she was in my clinic, because she made me leave the clinic door open; shutting the door made her feel confined. I was also instructed not to call her “ma’am,” because this made her feel old. There were a number of other rules that I accommodated, wordlessly, knowing that I did not stand a chance of winning any argument with her.

When I saw that her chronic kidney disease had jumped from stage 3 to stage 5, I knew, metaphorically, that this would be the end of her. She was fiercely independent, and I knew that relying on friends and family to take her back and forth to dialysis sessions, three times weekly, would kill her inside. So she left on her own terms; before dialysis could be initiated, she ended up in our emergency department, hypotensive, with polymicrobial sepsis that was resistant to everything that was thrown at it. She left as she would have wanted, in a blaze of defiant glory that suited her personality more than any end I could have imagined for her.

And now, to number four. I had met her by accident. She was scheduled to see my colleague, whom she had met during a prior hospitalization. She had arrived on time for her appointment, but a week early. My colleague was out of town, and the patient, who was reluctant to make the long drive to Richmond again the next week, had asked if I could see her, instead. I agreed, but insisted that she wait until I was finished seeing my own clinic patients. I remember seeing her husband through the crack of the door, sitting patiently as I ran past, ministering to patients I thought of as mine.

She became one of those patients, and I managed to get her through a lung resection, a fistula repair, a bout of sepsis and other long-forgotten complications. Along the way, I learned about her teenaged children and her love for them, her antebellum house and her extensive garden. The physician–patient relationship is an odd form of intimacy; her friends and family all knew who I was, although I had never met any of them.

I know that now, because when I met them at the memorial service, each of them knew exactly who I was. I could see the look of puzzlement melt into recognition when they heard my name, and I was greeted warmly, like a long-lost cousin arriving at the family reunion.

In church, at some point during the service, there is a ritualized greeting. The minister, standing at the pulpit, looks upon the congregation, and intones, “Peace be with you.” The congregation then murmurs back, “and also with you.” The call-and-response is so ingrained in my mind that if you greeted me with the same words in the middle of the street, the response would come, even before I had completely registered the incongruity.

These words echoed in my head during the memorial service, when I noticed that I had fallen into another ritualized greeting of sorts. “Thank you for coming,” each family member would say. “I am sorry for your loss,” I would respond. And thus, I met, for the first time, my patient’s mother-in-law, her siblings and her two children, who were old enough to be expected to attend the service, but not old enough to say goodbye. Meeting her daughter was the hardest. As she spoke, her words were almost trapped by her trembling lower lip, and I could see the tears glistening in her eyes. I fell silent. I had no words for her.

1 in 2

Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and is defined by three aspects: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Rates of burnout and depression are substantially higher among physicians than they are among the general population.1

The concept of physician burnout is becoming widely recognized, even by the lay press. A story by the CBS News Division stated: “If you’ve ever worried that your doctor seems burned out on the job, you may be right. Physicians are busier than ever, and hospitals are worried that as their staff gets overwhelmed, the quality of care goes down and medical errors go up.”2 Bento Soares, the senior associate dean for research at the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Peoria states, “We have been predominantly concerned with the technical skills and the knowledge that are required for the practice of medicine, but we forget that there’s an individual that’s delivering that care.”3

The acuity of our patients plays a role. For many of the patients under my care, it is inevitable that they will suffer a complication of their disease that I was not clever enough to prevent, or a complication of a drug that I prescribed, which is a heavy burden to bear for five clinics every week. Also, we are not fooling anyone. Patients recognize when we are burned out, and when they sense this, they are less likely to follow through on our advice.4

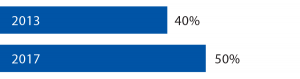

Data collected by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicates that burnout affects physicians, nurses and physician assistants in approximately equal numbers.5 In the first nationwide survey of physician burnout, conducted by Medscape in 2013, approximately 40% of physicians reported experiencing symptoms attributable to burnout, which they had defined as experiencing a loss of enthusiasm for work, feelings of cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment.6 By 2017, that number had increased to one out of every two physicians.7

Physicians respond to burnout by giving up and giving in. In one study, published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, physicians reporting one or more symptoms of burnout had a 43% greater likelihood of reducing their clinical responsibilities in the ensuing 24 months.8 Burnout has the potential to affect physicians both in and out of the workplace. Not surprisingly, burnout seems to impact adversely both healthcare and patient safety.9 Perhaps more surprisingly, physicians who complain of burnout also find it difficult to enjoy life outside of work.7

Physicians have the highest risk of suicide of any profession. This is an upsetting statistic that I was reluctant to put on the page, but it is that inclination to avoid difficult discussions that, frankly, got us into this mess in the first place. An inability to acknowledge our own faults and failings and, more importantly, that these faults and failings do not make us bad doctors, is how the cycle of burnout begins. Every year, 400 physicians take their own lives.10 It is a grim fact that every year, it takes three medical school classes to replace the physicians that we have lost to suicide.

There is proof that rheumatology is moving up in the world, but not in a good way. The 2017 Medscape Physician Lifestyle Survey contacted more than 14,000 physicians in more than 30 specialties.7 Interestingly, rheumatologists were the sixth most likely group to report experiencing burnout, topped only by specialists in emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, general internal medicine, and infectious disease. Just two years prior, rheumatology was toward the bottom of that list, with only allergy, ophthalmology, gastroenterology, pathology, psychiatry, and dermatology reporting greater levels of job satisfaction.

Changes in healthcare delivery seem to be driving the increased prevalence of burnout among healthcare providers. The American Medical Association has identified multiple potential drivers of burnout, including loss of control of work, increased performance measurement, the increasing complexity of medical care, implementation of electronic record and profound inefficiencies in the practice environment.11 A recent commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine notes, “Increasing clerical burden is one of the biggest drivers of burnout in medicine. … Little of this work is currently reimbursed. Instead, it is done in the interstices of life, during time often referred to as ‘work after work’—at night, on weekends, even on vacation.”12

All of these factors impact workflow and care provider–patient interactions. Being a physician has always been stressful; burnout has become an issue because we now find ourselves busy doing the wrong type of work for our patients, work that does not improve our patients’ lives. Burnout seems to be the inevitable result of good physicians who are trapped in a bad system and try to serve as a bulwark between what our patients need and what our care delivery system allows us to provide.

Physician burnout is becoming increasingly prevalent. Only by examining these issues openly & honestly can we hope to stem the tide.

The Way Forward

The fault, as Shakespeare wrote, lies not in the stars, but in ourselves.13 Perhaps it should not be surprising that the same personality traits that led us to medicine and professional success are the fundamental cause of our tendency to burn out. To address these faults, several approaches have been used, including the following:

- Mindfulness refers to focusing on the present, through meditation and other techniques, and letting go of past burdens or future worries. The technique has been used successfully to treat anxiety, depression and pain. The concept dates back to the 1970s, but its cultural currency is exploding, culminating in A Mindful Nation, a book written by Congressman Tim Ryan of Ohio, regarding the impact of mindfulness on his district and his own life.14

- Resilience refers to the ability to approach stress with optimism and with humor. The term was originally developed by psychologists to describe children who managed to thrive in the face of adversity. The modern concept implies that resilience may not just be an inborn trait; it can be taught. Resilience among physicians is associated with a number of practices, including taking time for leisure activities, cultivation of relationships with colleagues and friends, limiting work hours and acknowledging medical uncertainty and medical errors when they arise.15

- Self-compassion may be the most difficult of the three to practice, because it involves learning to forgive one’s own imperfections. This can be a particularly tall order, because medicine tends to attract people who are inclined toward competitive perfectionism. Several academic centers have pioneered the use of cognitively based compassion training, which trains clinicians to celebrate successes, rather than obsess over failures.16

Starting by focusing on the individual physician is particularly important because burnout may be contagious. Just as a rising tide lifts all boats, a burned-out physician’s attitudes and beliefs may spread throughout an organization. Thus, treating an individual may prevent an epidemic.

Some argue, however, that focusing on the individual may be prioritizing expediency over efficacy. Christine Sinsky, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association, notes that “to start with individual changes is like telling the canary in the coal mine that he should just try harder.”17 The sea change that has taken place over the past several years is the recognition that burnout is an organizational problem that requires an organizational approach.

Percentage of Physicians Who Reported Symptoms of Burnout6,7

The American Medical Association defined the triple aim of healthcare as lower costs, better outcomes and improved patient cares. More recently, the American Medical Association has updated this to include a fourth aim: clinician well-being. To promote this latest aim, the American Medical Association has created the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine, which serves as a resource for hospitals, medical centers and other organizations to promote clinician wellness. The organization also provides resources to help prove to administrators that promoting clinician wellness makes good financial sense. The foundation argues that “a more engaged, satisfied workforce will provide better, safer, more compassionate care to patients, which will, in turn, reduce the costs of care.”11

The argument is compelling. Every year, 7% of physicians will withdraw from providing clinical care because of burnout. Nationwide, it costs, on average, half a million dollars to recruit and train a physician to replace one who has left the workforce.11 With this in mind, the cost of initiatives to support clinician wellness start to seem like a pittance.

The importance of addressing burnout in the workplace seems like a no-brainer, so much so that the American Medical Association has trademarked the phrase Joy in Medicine, perhaps expecting that this will be the great advance in medicine for our generation. I certainly hope so. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the American College of Surgeons and other professional organizations all agree that burnout must be addressed urgently, and many institutions have followed suit, with public initiatives to put the joy back in medicine.

There’s the rub. It is easy to agree that burnout must be addressed at an institutional level, harder to institute the necessary changes and harder still to make physicians feel that substantial changes have taken place. When asked what his institution was doing to address burnout, one participant in a New England Journal of Medicine-sponsored survey responded curtly: “Not enough.” Other responses included the phrases, “lip service,” “administrative denial” and “talking about the problem in committees but no action plan yet.”18

Talk is not enough. A colleague of mine likes to say that the answer is money, no matter what the question is, and that rule probably applies in this case as well. Addressing burnout will result in obvious long-term gains, but at short-term cost. Convincing our administrators that the short-term cost is worth it is our responsibility, and it is an important burden to bear, because we cannot care for others if we cannot care for ourselves.

I was thinking about all of these issues on my drive home from Richmond. I spent an hour at the memorial service, and with a two-plus hour drive to Baltimore, I arrived back at my house around 10 at night. I sank into a chair, put up my feet and nodded off, exhausted by the day’s events.

The next morning, I went to work.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, is an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program.

Fast Facts: Rheumatologists Are Burning Out—Fast

In 2017, rheumatologists were the 6th most likely group to report experiencing burnout, topped only by specialists in emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, general internal medicine and infectious disease.7 Just two years prior, rheumatology was toward the bottom of that list, with only allergy, ophthalmology, gastroenterology, pathology, psychiatry and dermatology reporting greater levels of job satisfaction.

Fast Facts

- Rates of burnout and depression are substantially higher among physicians than they are among the general population.1

- Physicians reporting one or more symptoms of burnout have a 43% greater likelihood of reducing their clinical responsibilities in the ensuing 24 months.8

- Every year, 7% of physicians will withdraw from providing clinical care because of burnout.11

- Every year, 400 physicians take their own lives.10

References

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbre LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Dec;90(12):1600–1613.

- Physician burnout is on the rise. CBS News. 2017 May 15.

- Herrington C. Hospitals address physician burnout by focusing on mindfulness, empathy. Peoria Public Radio. 2017 Jun 21.

- Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: Exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008 Jan–Mar;33(1):29–39.

- Lyndon A. Burnout among health professionals and its effect on health safety. Patient Safety Network, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2016 Feb.

- Peckam C. Rheumatologist lifestyles—linking to burnout: A Medscape survey. Medscape. 2013 Mar 28.

- Peckham C. Bias, burnout, race: What physicians told us about the issues. Medscape. 2017 Jan 10.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA. Potential impact of burnout on the US physician workforce. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016 Nov;91(11):1667–1668.

- Saylers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety of healthcare: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Apr;32(4):475–482.

- Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017 Jun 21;7(6):e015141.

- Linzer M, Guzman-Corrales L, Poplau S. Preventing physician burnout. AMA Steps Forward.

- Wright AA, Katz IT. Beyond burnout—redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. New Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 25;378(4):309–311.

- Shakespeare W. Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene III, L 140–141.

- Ryan T. A Mindful Nation: How a simple practice can help us reduce stress, improve performance, and recapture the American spirit. Carlsbad, Calif. Hay House Self Publishing, 2012.

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017 Jan;92(1):129–146.

- Erikson M. Good leadership, self-compassion key to tackling physician burnout. Stanford Medicine News Center. 2017 Oct 17.

- Rosenfeld J. Fighting physician burnout at three levels. Medical Economics. 2017 Nov 16.

- Swensen S, Shanafelt T, Mohta NS. Leadership survey: Why physician burnout is endemic, and how health care must respond. NEJM Catalyst Insights Report. 2016 Dec 8.