A 27-year-old, left-handed man was referred to our ultrasound clinic for left elbow pain.

History

The patient had been a pitcher on a Minor League Baseball team. Two years before, he developed sudden, severe medial elbow pain while pitching in a game. The pain was associated with some tingling down the left medial forearm. The pain precluded further pitching. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a major medial collateral ligament (MCL) tear.

He subsequently underwent Tommy John surgery, in which his MCL was reconstructed using his own palmaris longus tendon. He did not have an ulnar nerve transposition during this procedure. He did well with rehabilitation after surgery until one year postoperative when, while pitching a live game, he developed recurrent left medial elbow pain.

He described the pain as a sharp explosion that occurred when the elbow was fully extended, but not with elbow flexion. The new pain differed from the pain of tearing his MCL in that he could continue to pitch (albeit with escalating exacerbation), and there was no sensation of popping, snapping or paresthesia with either flexion or extension of the elbow.

Conservative follow-up treatment and rehabilitation did not improve the pain. Repeat MRI revealed an intact MCL autograft. An intra-articular corticosteroid injection was ineffective. He was released from the organization and presented to our ultrasound clinic seeking relief for his pain and hoping to resume his pitching career.

Exam

The examination revealed a well-healed incision over the left medial elbow. The medial epicondyle was nontender. No effusion was present, and his range of motion was normal. With elbow flexion, there was a suggestion of subluxation of the ulnar nerve outside the ulnar sulcus. On elbow extension, the ulnar nerve retracted back into the ulnar sulcus. No palpable snapping was noted on elbow flexion. A dynamic valgus stress test was negative. Left upper extremity muscle strength and sensation were intact.

Ultrasonography revealed the palmaris longus graft, which stretched from the medial condyle to the sublime tubercle of the ulna, was intact both statically and dynamically. No tears were noted. The ulnar nerve was 9 mm² in cross-sectional area, a normal value.

In elbow extension, ultrasonography revealed the ulnar nerve to be resting normally in the ulnar groove and without evidence of compression in the true cubital tunnel under Osborne’s ligament.

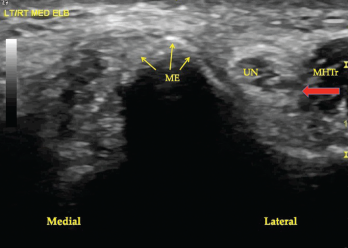

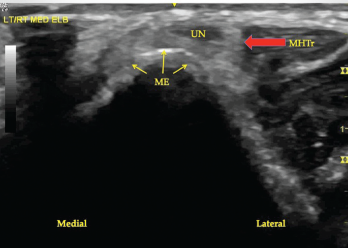

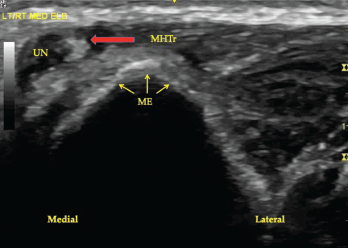

Figure 1. A transverse view of the ulnar groove in full elbow extension. The red arrow indicates the advancing edge of the MHTr.

A dynamic view of the ulnar nerve with elbow flexion revealed complete dislocation over the medial epicondyle followed by the medial head of the triceps (MHTr) (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

No sonographic evidence of snapping of either the ulnar nerve or the MHTr was found. The ulnar nerve on longitudinal view appeared to be normal without areas of compression or dilation.

The patient was diagnosed with ulnar nerve instability and dislocation of the ulnar nerve and MHTr. It was postulated that upon sudden elbow extension while vigorously throwing a baseball, ulnar nerve relocation occurred, with the ulnar nerve traumatically impacting either against the outside medial epicondyle and/or in the ulnar sulcus, producing severe pain.

Three days later the patient underwent anterior subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition, in which the ulnar nerve was removed from the cubital tunnel. The MHTr was unaltered to avoid affecting his pitching velocity.

Figure 2. A transverse view of the ulnar groove in partial elbow flexion. Note the ulnar nerve and the medial head of the triceps muscle are both subluxing toward the apex of the medial epicondyle.

Three months later the patient resumed throwing a baseball and was soon able to painlessly pitch a complete season for a professional baseball team. He is now 14 months out from surgery and remains symptom free. His fastball remained greater than 90 mph and his earned run average was 2.32.

Causes of Medial Elbow Pain

In this age group, causes of medial elbow pain include medial epicondylitis, MCL injury with or without elbow instability, ulnar neuritis, snapping ulnar nerve, snapping triceps, olecranon osteophytes, olecranon stress fracture and flexor pronator strain.1

Ulnar neuritis may be caused by entrapment in different locations, but most commonly under Osborne’s ligament.1 Such entrapment is called cubital tunnel syndrome.2

Snapping ulnar nerve occurs in elbow flexion (between 70º and 90º) when the ulnar nerve dislocates over the apex of the medial epicondyle. This is typically painful and often accompanied by a palpable and audible snap.3,4 Neurologic symptoms from the snapping ulnar nerve are rarely reported, with the most common symptom being localized pain.3

Figure 3. A transverse view of the ulnar groove in full elbow flexion. Note the ulnar nerve and the medial head of the triceps muscle have both dislocated over the apex of the medial epicondyle. Key: UN, ulnar nerve; MHTr, medial head of the triceps muscle; ME, medial epicondyle.

In snapping triceps, with elbow flexion of approximately 115º, the distal MHTr also dislocates over the apex of the medial epicondyle, with or without audible/palpable snapping, and may push the ulnar nerve out of the groove (subluxation), perhaps to a point over the apex of the medial epicondyle (dislocation).1,3,4 Hypertrophy of the triceps may be a predisposing condition to ulnar nerve dislocation.1

Tommy John Surgery

Orthopedic surgeon Frank Jobe first performed ulnar collateral ligament (also called the MCL) reconstruction on baseball pitcher Tommy John in 1974.5 The procedure was named for the first recipient.

In this procedure, a soft tissue graft, most commonly a palmaris longus or gracilis autograft, is used as a functional substitute for the anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament complex. The ulnar nerve may or may not be transposed as a part of this procedure, based on the patient’s history, physical exam findings, imaging studies and surgeon preference in consultation with the patient.

Most patients do well, with good to excellent results and a high rate of return to play after this surgery, but complications do occur.6 The average complication rate is 10.2%, with the majority (6.7%) of complications being ulnar nerve neurapraxia.6

Since Dr. Jobe performed the first Tommy John surgery in 1974, the incidence of this procedure has risen dramatically. In a recent study looking at the prevalence of medial ulnar collateral ligament surgery in 6,135 current professional baseball players, 13% of all Major and Minor League Baseball players and an astonishing 20% of Major and Minor League pitchers have undergone Tommy John surgery.7

What about the MCL in asymptomatic professional baseball pitchers? There is a substantial incidence of MCL abnormalities on MRI in asymptomatic professional baseball pitchers. Two studies revealed a 15% and a 27% incidence of asymptomatic MCL tears in this population.8,9

Out of the Ulnar Groove

Since at least 1896, physicians have known the ulnar nerve may move out of the ulnar sulcus in elbow flexion; however, the clinical ramifications have been better understood only in the past few decades.10 The term ulnar nerve instability was described in 1977. This occurs when the ulnar nerve chronically subluxes and relocates with elbow flexion and extension.11 This increases ulnar nerve vulnerability to trauma, particularly when it lies superficially on the medial epicondyle.12 The most common probable cause of ulnar nerve instability is ligamentous laxity.12

Hypertrophy of the MHTr acquired from exercise is also postulated to be a cause of ulnar nerve instability and snapping triceps syndrome.1,13,14 Ulnar nerve instability may occur with or without radiating paresthesia and with or without snapping of either the ulnar nerve or the MHTr.12,15 It is a separate entity from ulnar nerve compression, although a friction neuritis may produce radiating paresthesia mimicking cubital tunnel syndrome.12

Snapping elbow is undetected by standard (static) radiographs and MRI.3 Thus, dynamic ultrasonography is becoming the gold standard when evaluating medial elbow pain occurring with movement.3,4 Prior to the use of dynamic ultrasonography, nonroutine, flexion and extension MRI views were required to image a snapping triceps.4,5,16 Dynamic ultrasonography is inexpensive and simple to perform at the point of care.

Discussion

In our patient, the history, physical examination and dynamic sonographic study did not reveal snapping of either the ulnar nerve or the MHTr during elbow flexion. The patient, therefore, did not suffer from classic snapping elbow, either snapping ulnar nerve or snapping triceps muscle. Pain occurred only at the end of rapid and forceful full elbow extension, that is, the motion utilized when throwing a baseball. Because the dislocated ulnar nerve did not produce paresthesia, either with dislocation or forceful relocation, electrophysiological studies were not determined to be necessary.

Static ultrasonography done during elbow extension verified the ulnar nerve to be in its proper position in the ulnar groove. Dynamic ultrasonography revealed the ulnar nerve to completely dislocate out of the ulnar groove during elbow flexion, being propelled over the medial epicondyle by the hypertrophied MHTr. Vigorous relocation of the ulnar nerve upon rapid elbow extension was the source of localized medial elbow pain. Complete resolution of the pain occurred after ulnar nerve transposition. The MHTr muscle was left intact during surgery and was not the source of medial elbow pain.

We describe this as ulnar nerve relocation pain, and we propose characterizing this as a syndrome. The elements of this proposed syndrome would be: sonographic demonstration of ulnar nerve dislocation pushed by a hypertrophied and dislocating MHTr muscle, with pain occurring at the end of rapid elbow extension. The typical clinical setting would be in a professional athlete who repetitively throws.

In patients with medial elbow pain and particularly in those with pain occurring after MCL reconstruction procedure, it may be reasonable to perform an ultrasonography exam, including a dynamic exam to evaluate for a cause not apparent on an MRI.

Further, given the substantial incidence of asymptomatic, incidental MCL tears on MRI in professional baseball pitchers, consideration of ulnar nerve relocation syndrome may help avoid unnecessary MCL reconstruction surgery or prompt consideration of concomitant ulnar nerve transposition, if such surgery is deemed necessary.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

A. Lee Day, MD, RMSK, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is a rheumatologist at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C., and is an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine.

A. Lee Day, MD, RMSK, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is a rheumatologist at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C., and is an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Prisma Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Christopher G. Mazoue, MD, completed a sports medicine fellowship at the American Sports Medicine Institute. He is an associate professor and chair of the USC Department of Orthopedic Surgery and the Prisma Health USC Orthopedic Center, and medical director for the USC Gamecocks athletes.

Christopher G. Mazoue, MD, completed a sports medicine fellowship at the American Sports Medicine Institute. He is an associate professor and chair of the USC Department of Orthopedic Surgery and the Prisma Health USC Orthopedic Center, and medical director for the USC Gamecocks athletes.

Ulnar Nerve Relocation: A New Syndrome?

Elements of this proposed syndrome would be: sonographic demonstration of ulnar nerve dislocation pushed by a hypertrophied and dislocating MHTr muscle, with pain occurring at the end of rapid elbow extension.

The typical clinical setting would be in a professional athlete who repetitively throws.

References

- Barco R, Antuña SA. Medial elbow pain. EFORT Open Rev. 2017Aug 30;2(8):362–371.

- Cutts S. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Jan;83(975):28–31.

- Bjerre JJ, Johannsen FE, Rathcke M, Krogsgaard MR. Snapping elbow—A guide to diagnosis and treatment. World J Orthop. 2018 Apr 18;9(4):65–71.

- Jacobson JA, Jebson PJ, Jeffers AW, et al. Ulnar nerve dislocation and snapping triceps syndrome: Diagnosis with dynamic sonography—report of three cases. Radiology. 2001 Sep;220(3):601–605.

- Jobe FW, Stark H, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986 Oct;68(8):1158–1163.

- Somerson JS, Petersen JP, Neradilek MB, et al. Complications and outcomes after medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A meta-regression and systematic review. JBJS Rev. 2018 May;6(5):e4.

- Leland DP, Conte S, Flynn N, et al. Prevalence of medial ulnar collateral ligament surgery in 6135 current professional baseball players: A 2018 update. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Sep 25;7(9):2325967119871442.

- Gutierrez NM, Granville C, Kaplan L, et al. Elbow MRI findings do not correlate with future placement on the disabled list in asymptomatic professional baseball pitchers. Sports Health. 2017 May/Jun;9(3):222–229.

- Garcia GH, Gowd AK, Cabarcas BC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of the asymptomatic elbow predict injuries and surgery in Major League Baseball pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Jan 20;7(1):2325967118818413.

- Cobb F. IV. Report of a case of recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve cured by operation: With summary of previously reported cases. Ann Surg. 1903;38(5):652–663.

- Lazaro L 3rd. Ulnar nerve instability: Ulnar nerve injury due to elbow flexion. South Med J. 1977 Jan;70(1):36–40.

- Xarchas KC, Psillakis I, Koukou O, et al. Ulnar nerve dislocation at the elbow: Review of the literature and report of three cases. Open Orthop J. 2007 Sep 24;1:1–3.

- Spinner RJ, Goldner RD. Snapping of the medial head of the triceps and recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve. Anatomical and dynamic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998 Feb;80(2):239–247.

- Rioux-Forker D, Bridgeman J, Brogan DM. Snapping triceps syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2018 Jan;43(1):90.e1–90.e5.

- Watts AC, McEachan J, Reid J, Rymaszewski L. The snapping elbow: A diagnostic pitfall. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009 Jan–Feb;18(1):e9–e10.

- Spinner RJ, Hayden FR Jr., Hipps CT, Goldner RD. Imaging the snapping triceps. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996 Dec;167(6):1550–1551.