Falls are a major hazard for persons with arthritis, especially postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, because of a fall’s major impact on morbidity and mortality. People with a rheumatic disease such as osteoporosis, osteoarthritis (OA), ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and other types of inflammatory polyarthritis are among those at high risk for falls and, thus, for injury. Interference with mobility, flexibility, gait, and musculoskeletal strength are common effects of arthritis, creating susceptibility to falls. Lower limb arthritis has been identified as a significant predictor of falls.1

In an analysis of 16 studies on risk factors for falls in older adults, arthritis was identified as one of the most significant; other common factors identified included conditions as noted above that interfere with physical function (i.e., muscle weakness, gait deficit, and balance deficit).2 Those with arthritis affecting the lower limbs were found to have significantly more falls and falls with greater injury than those without arthritis over a 12-month period. A study focusing on rheumatoid arthritis found the greatest risk factors to be taking an antidepressant medication and self-reported impairment in lower limb function with difficulty in walking and rising.3 Another study of 316 women with inflammatory polyarthritis identified the risks (all at a confidence interval of 95%) of those who had fallen as a higher swollen joint count (of 10 joints), greater visual analogue pain intensity scores, higher Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) total and individual domain scores, lower levels of outdoor activity, impaired vision, and impaired general health.4

Age as a Risk Factor

Advancing age is a common factor associated with the incidence of falls and the seriousness of resulting complications. About 35% to 40% of community-dwelling persons between the ages of 65 and 75 fall each year.2 In developed countries, 10% to 20% of older adults fall twice or more. Even though fewer than 5% of these falls result in fractures, the total number becomes significant.5

Age, in combination with rheumatic disease, becomes a major risk factor for falls.6 Although rheumatic disease affects persons of all ages, it is more prevalent in the older adult population.7 Two conditions that increase with age are osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Both place the individual at increased risk for falls due to muscle weakness and stiffness of the hip and knee joints, resulting in unsteadiness. In the case of osteoporosis that is characterized by low bone density, the risk of fracture associated with falls increases.

Consequences of Falls

The costs of fracture are high, both in healthcare dollars and in quality of life, especially if the hip is fractured.8 The cost of osteoporosis-related fractures alone was estimated to be $19 billion in 2005.9 Other consequences of falls include lacerations, soft-tissue injuries, abrasions, inability to perform daily living activities for a period of time,10 activity avoidance, and fear of falling.11 These injuries may lead to hospitalization or a prolonged recovery period. Falls may be responsible for permanent, and often declining, changes in the person’s lifestyle. Injuries or fractures can lead to increased weakness and impaired mobility, making it impossible to resume activities that were possible before the fall.

Fear of Falling

Activities are not only limited by actual falls but also by the fear of falling. This fear increases with the number of falls experienced,11 though this fear is also common among nonfallers.12 Half of community-dwelling elders are fearful of falling. This percentage is somewhat higher (almost 60%) for patients with a diagnosis of RA; within this group, those who are fearful walk more slowly, have more comorbidities, and experience greater pain intensity than do those who are not.13 People who are afraid of falling may become debilitated by restricting their physical and social activities.14 It is important, therefore, to assess not only the fear of falling, but other risk factors as well. If individuals understand what their risk factors are, they can then take some positive steps to reduce them, thus increasing their confidence in performing activities.

Interference with mobility, flexibility, gait, and musculoskeletal strength are common effects of arthritis, creating susceptibility to falls.

What Rheumatology Practitioners Can Do

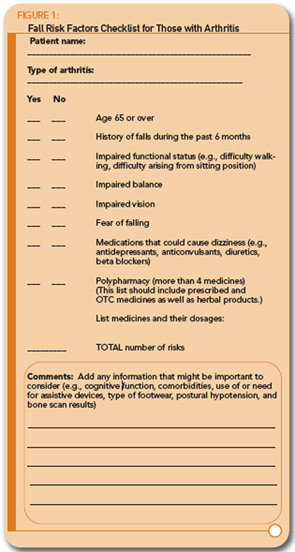

Assessment: Assessment is the first action that practitioners can take. Every community-dwelling person with arthritis should have a falls-related assessment to reduce the possibility of falling. Individual variations to include in such an assessment include age, comorbidities, history of falls, medications the person is taking, functional status, vision, and fear of falling. A Falls Risk Checklist can easily be kept as part of the patient’s record. A suggested checklist is provided in Figure 1 (see pg. 16). The items represent the most common risks exhibited by those who attended a falls clinic.15 The number of risks that might predict one’s likelihood of falling is unknown; but, obviously, a greater number of risks would make falling more probable. Any risks that are present, along with age and a diagnosis of arthritis, should be noted and addressed with the patient.

Each of these risk factors can be easily and quickly assessed during an office visit. During assessment, someone should be nearby as a safety precaution, and any of the usual aids (e.g., cane or walker) should be used. If this risk assessment suggests the person is “at risk” for falling, further assessment and interventions can be recommended. Just a few simple screening tests are described; more extensive tests should be done when that seems indicated.

Physical function, especially of the lower extremities, can be evaluated through observation of the patient’s mobility and gait, as well as by self-report. Individuals can be asked to perform simple movements such as walking across the room and rising from a chair. Notations to make on the patient’s record might include any observation of unsteadiness, noticeable muscle weakness, and limited range of motion (e.g., in the ankles, knees, or hips). Walking can also give some indication of one’s ability to balance. Are persons steady as they rise from a sitting position and begin walking? Balance can be checked by noting if the patient can stand with eyes closed in a “near-tandem” position (i.e., with the feet 1 inch apart and the heel of the front foot 1 inch in front of the toe of the back foot) for 30 seconds. Inability to do this indicates poor balance.6 If more extensive assessment seems warranted, specific tests such as the HAQ-DI16,17 and the Timed Up and Go Test18 are available. Administering these tests takes more time, but they probably can be accomplished in approximately 20 minutes with most patients.

Vision screening is important. Because of the number of problems (e.g., visual acuity, cataracts, macular degeneration) that can affect how one sees, one of the most basic questions to ask is, “Have you had your vision tested by an eye doctor during the past year?” Self-report of vision problems may also indicate risk of falling. A simple screening test that can be done is a low-contrast visual acuity test, using a chart similar to the Snellen chart and testing the individual’s ability to read at a distance of 10 feet or three meters. This alternate test is recommended because those with low-contrast visual problems may have more problem seeing those things within their environment that could be hazardous.6 These charts are available for purchase.

Assessing the fear of falling is also important to know whether measures should be taken to increase the person’s confidence in performing independent activities. Again, one question may be asked: “Do you limit any of your activities because you are afraid of falling?” If the answer is “yes,” then further questions may be asked to determine 1) if there are specific factors (e.g., impaired physical function or vision) contributing to this fear, and 2) how this fear is affecting one’s function. Most intervention studies for fear of falling have used a version of the Falls Efficacy Scale19 to assess the confidence one has in performing common activities (e.g., getting in and out of a chair, walking around the house) without falling. It provides a practical approach to assessment, as it should take approximately 5 minutes or less in most cases.

Both polypharmacy (i.e., taking more than four medicines) and dizziness have been identified as common fall risk factors. A review of medicines the person is taking, including over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and herbal preparations, thus, becomes an important part of the assessment. Because dizziness is one of the risk factors, medicines that could possibly cause dizziness should be discussed with the patient to determine if this could be a contributing factor. Dizziness as a possible side effect should be discussed, as appropriate, when a new medicine is started. Antidepressants are commonly cited as a problem because they can lower blood pressure, resulting in dizziness. Some of the other drugs that may be an issue include diuretics, beta blockers, and anticonvulsants. It is not unusual for individuals to have several chronic conditions and take a number of different medications, especially as they age. Taking more than four medicines may signal that a reevaluation of drug therapy is needed. Factors important to consider include whether a different medicine might be more appropriate; whether the medicine dosage might be reduced, noting that older individuals generally need a smaller amount; when the medicine should be taken to lessen dizziness-related issues, and whether there are possible interactions that are causing harm.

Numerous other factors deserve consideration on an individual basis, including cognitive function, number and type of comorbidities, use of or need for assistive devices, and type of footwear. An additional test that importantly and indirectly relates to assessment for fall prevention is a bone density scan. Individuals with low bone mass are at higher risk for injury due to fracture when they fall. Any person who experiences a number of osteoporosis risk factors9 should be evaluated with a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, or DXA. It is important that those with validated low bone mass and high fracture risk be carefully evaluated for possible fall risks.

Intervention: Assessment follow-up depends on the individual findings. If individuals show that they do have fall-related risks, they should be referred to a comprehensive falls prevention program, if available, or to appropriate healthcare professionals. Much of the needed follow-up can be provided in the office, clinic, or home settings by a nurse or nurse practitioner and a physical therapist working in collaboration with the physician. Two components of a fall prevention program are needed and can be addressed in either setting; these include (1) discussion and education and (2) exercise and training.6,20 Involving individuals in their own preventive treatment is important for reducing their own falls, and fall risks will be largely dependent on adherence to prescribed activities.

Suggested education topics that cover fall-reduction factors include exercise, modifying the home environment for safety, desirable types of footwear, medical management such as vision testing, and proper use of assistive devices. Education may occur as individual or group discussion, supplemented by printed materials as appropriate. A variety of excellent printed and Internet educational resources are available. Examples include:

- What You Need to Know About Balance and Falls: A Physical Therapist’s Perspective. Published by the American Physical Therapy Association, 1999. (www.apta.org/AM/Images/APTAIMAGES/ContentImages/ptandbody/balance/BalanceFall.pdf)

- Check for Safety: A Home Prevention Checklist for Older Adults. Published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2006. (www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/toolkit/CheckListForSafety.htm)

- What You Can Do to Prevent Falls. Published by the CDC, 2006. (www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/toolkit/WhatYouCan DoToPreventFalls.htm)

Exercise and training are especially important for individuals with arthritis who are likely to experience problems related to mobility and physical function. Just telling one to exercise is not sufficient; rather, individual instruction and practice are needed. Important exercises include those that increase strength, balance, flexibility, and coordination. One of these that has resulted in positive outcomes, including the reduction of the fear of falling, is tai chi.14, 21 All new exercises should be planned to fit the individual’s abilities and interests, and they should be started slowly and carefully, preferably with the guidance of a physical therapist. When the individual feels comfortable performing the exercises practiced, these can be continued at home. Because adherence has been identified as an issue,15 providers should be sure to ask about activities at each office visit.

Exercise and training is especially important for individuals with arthritis who are likely to experience problems related to mobility and physical function.

Conclusion

Independence is an extremely important aspect of one’s quality of life, and it can be ended abruptly with a fall. Even if the individual makes an adequate recovery, the way one lives and functions can be affected by the fear of taking another fall.22 Rheumatology practitioners can assume a major role in preventing falls and decreasing the fear of falling by recognizing the issue, assessing the individual, and taking a proactive approach to ensure that each person receives appropriate follow-up and ongoing evaluation.

References

- Sturnieks DL, Tiedermann A, Chapman K, Munro B, Murray SM, Lord SR. Physiological risk factors for falls in older people with lower limb arthritis. J Rheum. 2004; 31:2272-2279.

- American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. Guidelines for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001; 49:664-676.

- Armstrong C, Swarbrick CM, Pye SR, O’Neill TW. Occurrence and risk factors for falls in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:1602-1604.

- Oswald AE, Pye SR, O’Neill TW, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for falls in women with established inflammatory polyarthritis. J Rheum. 2006; 33:690-694.

- Gregg, EW, Pereira MA, Caspersen, CJ. Physical activity, falls, and fractures among older adults: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000; 48:883-893.

- Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB. Falls in older people: Risk factors and strategies for prevention. Cambridge, UK: University Press; 2001.

- Hannan MT. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases. In: Robbins L, Burckhardt CS, Hannan MT, DeHoratius RJ, eds. Clinical care in the rheumatic diseases. 2nd ed. Atlanta, Ga.: American College of Rheumatology; 2001: 9-14.

- Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating high fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003; 51: 364-370.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Fast facts. Retreived March 31, 2008, from www.nof.org/osteoporosis/diseasefacts.htm

- Nachreiner N, Findorff MJ, Wyman JF, McCarthy TC. Circumstances and consequences of falls in community-dwelling older women. J Women’s Health. 2007; 16:1437-1446.

- Bertera EM, Bertera RL. Fear of falling and activity avoidance in a national sample of older adults in the United States. Health Soc Work. 2008; 33:54-62.

- Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, et al. Falls and fear of falling: Which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002; 50:1329-1335.

- Jamison M, Neuberger GB, Miller PA. Correlates of falls and fear of falling among adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 49:673-680.

- Zijlstra GAR, van Haastregt JCH, van Rossum E, van Eijk JTM, Yardley L, Kempen GIJM. Interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-living older people: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55:603-615.

- Hill KD, Moore KJ, Dorevitch ML, Day LM. Effectiveness of falls clinics: An evaluation of outcomes and client adherence to recommended interventions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008; 56:600-608.

- Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ-DI). Retrieved July 31,2008, from http://aramis.stanford.edu/downloads/HAQ%20-%20DI%202007.pdf

- The Health Assessment Questionnaire and the PROMIS HAQ (formerly called the HAQ 100) Stanford University School of Medicine Division of Immunology & Rheumatology (Revised August 2007). Retrieved July 31, 2008, from http://aramis.stanford.edu/downloads/HAQ%20Instructions%20(ARAMIS%20Site)2-14-08.pdf

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991; 39:142-148.

- Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990; 45:P239-P243.

- Swift CG. Identifying risk can reduce fall rates. Practitioner. April, 2007; 251:39-49.

- Haber, D. Health promotion and aging: Implications for the health professions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 1999.

- Kalb C. Aging. The meaning of falling. Newsweek. December 11, 2000; 136(24):63-64.