Discussion

In this report, we present three new applications of the MDHAQ. First, RAPID3 documented substantial improvement over six months in a patient with a non-rheumatic disease, pulmonary fibrosis, based on usual routine MDHAQ completion in the clinic waiting area. RAPID3 may be useful in many non-rheumatic diseases. All ambulatory individuals wish to be as functional and pain free as possible and experience overall well-being, reflecting the three RAPID3 components, which are identical to the RA core data set.

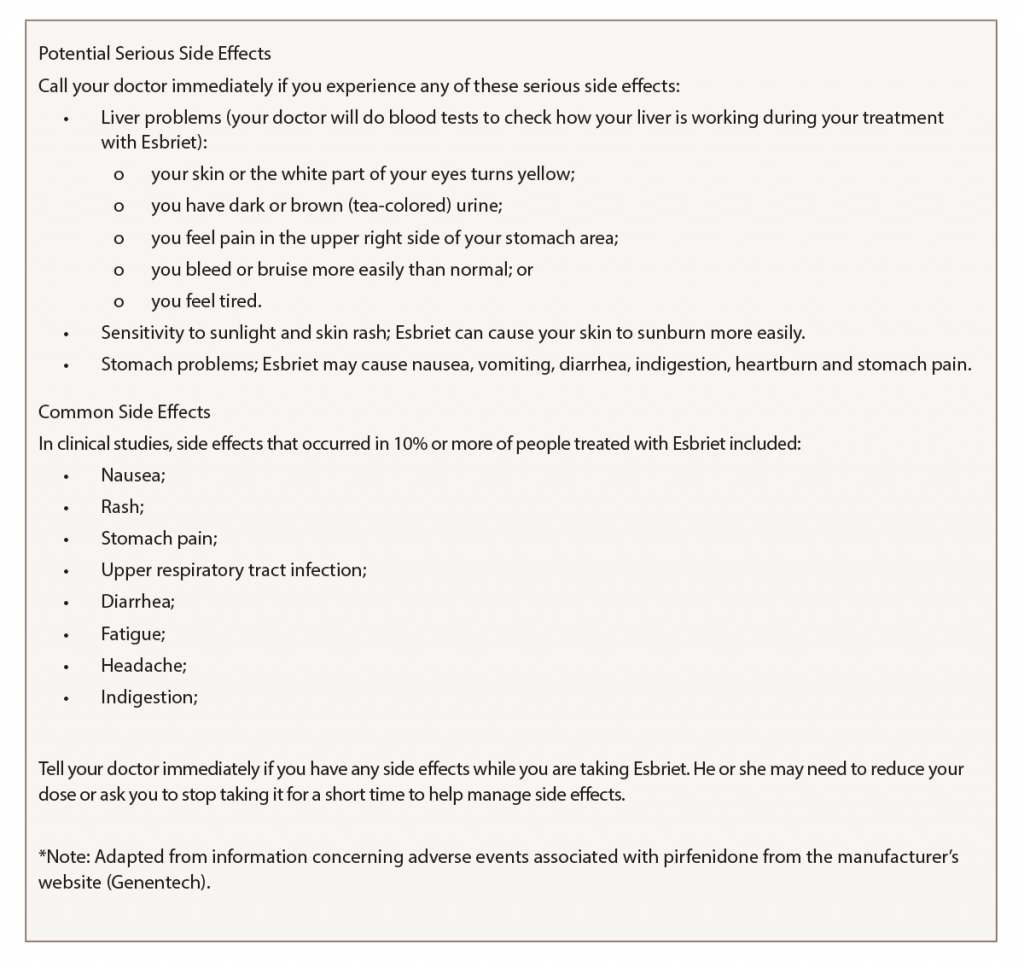

Second, a remote electronic MDHAQ documented adverse events to a medication, pirfenidone, as substantially elevated RAPID3 and fatigue VNS scores, and seven new specific symptoms (see Figure 2, opposite) which were listed as adverse events for pirfenidone (see Figure 3, above right). A face-to-face visit did not appear mandatory, because he reported an unchanged pulmonary situation and virtually all new symptoms could be attributed to the pirfenidone (and possible withdrawal from low-dose prednisone and methotrexate). Discontinuation of pirfenidone, reinstatement of 10 mg prednisone, contact if symptoms were worsening and remote electronic MDHAQ review two days later appeared reasonable to avoid further acute stress to an elderly patient who required continuous oxygen therapy. Clear improvement two and five days later were documented on the remote electronic MDHAQ symptom checklist, which would not have been available if only RAPID3 were queried.

Third, weekly remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring was effective to document clinical improvement according to RAPID3 and resolution of many symptoms according to the MDHAQ symptom checklist over 12 weeks, between Sept. 24 and Dec. 28 (see Figure 2, opposite).

Remote electronic monitoring cannot be applied to all patients. The patient in this case was highly intelligent and reliable, and a plan for a face-to-face visit if his clinical status worsened seemed reasonable. Weekly remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring could be a useful screening procedure for many (but not all) patients. Completion of a weekly electronic MDHAQ was estimated by the patient to involve about 10 minutes, or a total of two hours over 12 weeks, less than the door-to-door time required for a single face-to-face clinic visit.

The flow sheet of MDHAQ data available to the rheumatologist had considerable relevant information about the patient, perhaps as much or more than other doctors who conducted face-to-face visits without MDHAQ data. Nonetheless, no reimbursement to the rheumatologist was possible for weekly contact with the patient—sometimes with telephone feedback and sometimes with no feedback when it appeared unnecessary. Perhaps new payment procedures may be proposed in the future for improved management strategies that don’t involve face-to-face visits.

Note: The remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring was not conducted through the electronic medical record (EMR), but using software for which certification is pending. The patient was instructed not to include private medical information (e.g., name, date of birth, medical record number) on the remote MDHAQ used in his care. Having all patient care information in one EMR would appear to be optimal, but the many administrative complexities and limitations of the EMR may render this difficult and detract from optimal patient care.17 Summary information and the flow sheet were entered into the EMR as PDF files, which may have required less time than manipulating the EMR to incorporate the information.

Adverse events to medications are reported to be associated with 5% of U.S. hospital admissions, 10% in the elderly.18 Systematic remote electronic questionnaires appear cost effective and broadly acceptable to patients with cancer, diabetes, and pulmonary and psychiatric diseases.19 A recent report indicated timely recognition of adverse events in oncology patients using remote electronic monitoring of symptoms.20 Remote, weekly MDHAQ monitoring as a routine procedure for patients who initiate high-risk medications could proactively alert clinicians to early recognition of adverse events, including the possible need for a face-to-face visit, overcoming a current requirement for a telephone or “My Chart” contact or awaiting report by the patient at the next visit. This strategy could help reduce the high prevalence, morbidity and mortality of adverse events in current medical care.