Laura Mahony PhotographY; I Believe I Can Fly / shutterstock.com

The patient medical history is far more prominent in clinical decisions for rheumatology than for many common chronic diseases in which a gold standard biomarker, such as blood pressure or serum glucose, is applicable to diagnosis and management of all individual patients.1 Components of a subjective patient history may be recorded as structured, quantitative, standard, protocol-driven, scientific self-reported data on a patient questionnaire rather than as narrative descriptions.2,3

The multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) includes RAPID3 (routine assessment of patient index data), a 0–30 index of three 0–10 visual numeric scales (VNS) of physical function, pain and patient global assessment (see Figure 1).4,5 In about five seconds, RAPID3 gives information for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) similar to disease activity score 28 (DAS28) or the clinical disease activity index (CDAI), which require about 100 seconds to score.6 The ACR has endorsed RAPID3 as an outcome measure for RA, and it appears as widely used in U.S. clinical practice as any quantitative clinical index, perhaps in part because it is informative to monitor all rheumatic diseases studied.7-9

Many clinicians, pharmaceutical companies, patient advocacy groups and even the ACR website have extracted only RAPID3, which constitutes about 30% of the MDHAQ, for use—limiting the questionnaire’s clinical value. The full MDHAQ content includes a VNS for fatigue; a self-reported RADAI (RA disease activity index) painful joint count, which is useful in many rheumatic diseases; a 60-symptom checklist to serve as a review of systems and help clinicians recognize potential adverse events of medications; and recent medical history queries.4,10-12 In fact, the full MDHAQ adds considerable incremental information to RAPID3 and requires only 5–10 minutes of the patient’s time to complete vs. 2–5 minutes to complete only the RAPID3 section, ultimately saving time for both the doctor and patient.6 Example: Recent reports have documented that fibromyalgia assessment screening tools (FAST) on the MDHAQ, composed of the 60-symptom checklist, RADAI self-report painful joint count, and pain VNS and/or fatigue VNS, agree more than 80% with the polysymptomatic distress scale, a different questionnaire that constitutes the formal, revised 2011 fibromyalgia criteria.13-15

The full MDHAQ adds considerable incremental information to RAPID3 & takes just 5–10 minutes of the patient’s time to complete.

We present here a case report that illustrates three new applications of the MDHAQ involving RAPID3 and the 60-symptom checklist: 1) RAPID3 is informative to document substantial clinical improvement in a patient with a non-rheumatic disease, pulmonary fibrosis, based on routine MDHAQ completion in the rheumatology clinic waiting area; 2) the symptom checklist on a remote electronic MDHAQ, completed at home by a patient, can recognize adverse events to a medication; and 3) weekly remote electronic MDHAQ completion without face-to-face visits can be effective to document resolution of adverse events and subsequent clinical improvement.

Case Report

Pixsooz / shutterstock.com

A 78-year-old man with pulmonary fibrosis was referred to a rheumatologist on Jan. 19, 2018, because of a positive rheumatoid factor test. His joint examination was normal. Although reassured he did not have RA, he asked to be monitored by both a rheumatologist and a pulmonologist.

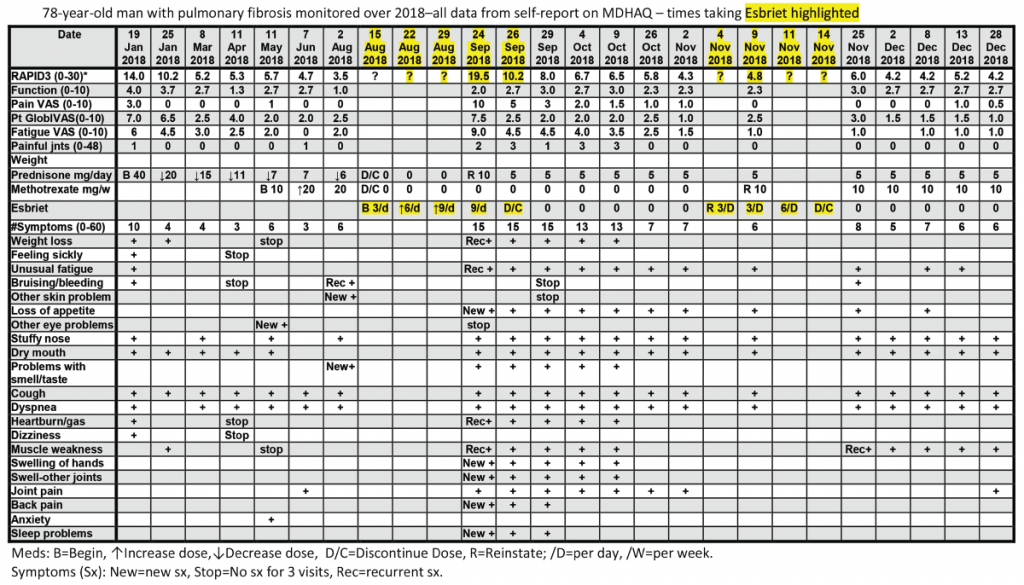

All patients with all diagnoses seen in the rheumatology division at Rush University Medical Center complete an MDHAQ at all routine visits. At the patient’s first visit, his RAPID3 score was 14/30 (high severity = 12–30), his fatigue score on the 0–10 VNS was 7/10, and he reported 10/60 symptoms (see Figure 2, below).6 He was treated with low-dose prednisone and methotrexate, experiencing substantial clinical improvement over the next six months, which was documented on the MDHAQ. On Aug. 2, the RAPID3 score was 3.5/30 (low severity = 3.1–6.0), his fatigue score was 2/10, and he reported 6/60 symptoms (see Figure 2, below), although he continued to require low-level oxygen.

On Aug. 15, his pulmonologist discontinued low-dose prednisone and methotrexate and prescribed 267 mg pills of pirfenidone (Esbriet), an anti-fibrotic agent, escalated over three weeks: three pills the first week, six the second and nine the third (see Figure 2, below).16 His next rheumatology appointment was scheduled for October.

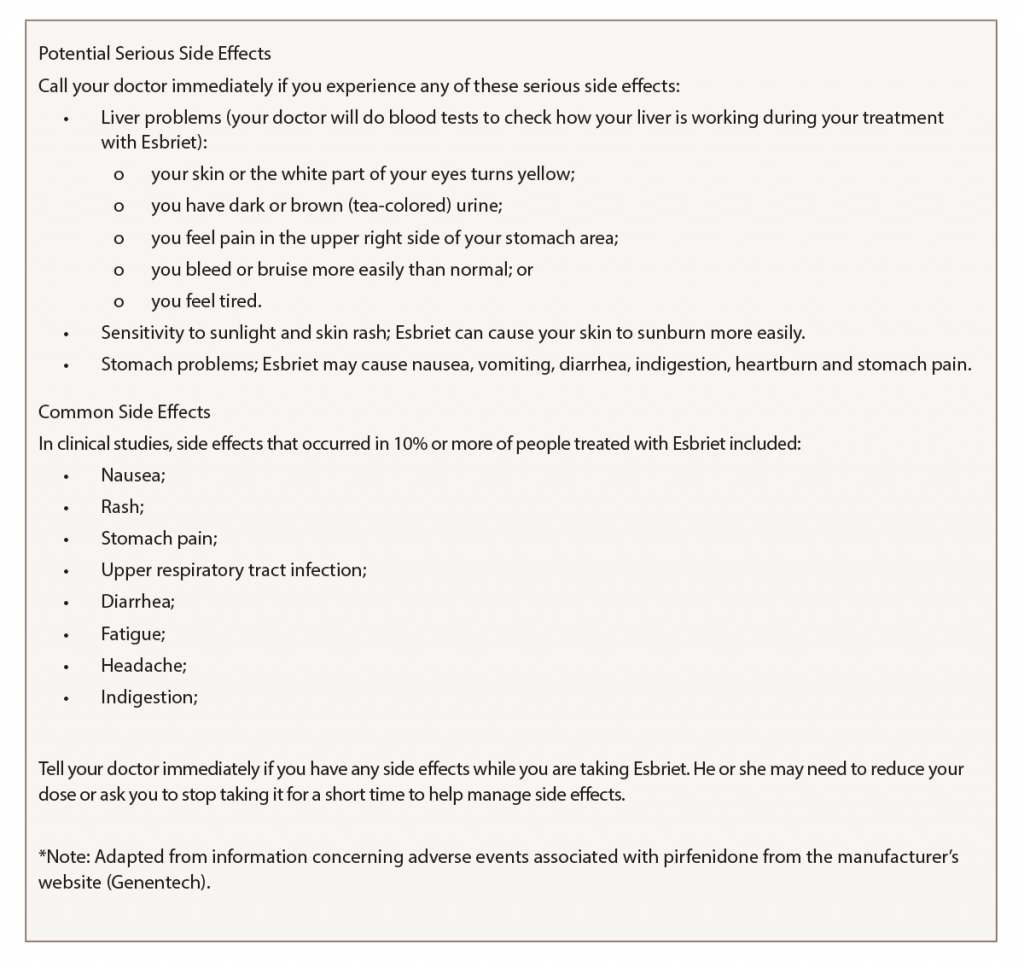

On Sept. 24, the patient telephoned the rheumatologist to report many new problems, although his pulmonary status was mostly unchanged—continuing to require oxygen. The rheumatologist sent the patient an electronic MDHAQ for completion at home to characterize his clinical status quantitatively for comparison with the Aug. 2 report. His new RAPID3 score was 19.5/30 vs. 3.5/30 on Aug. 2, his fatigue score was 9/10 vs. 2/10, and he reported 15/60 vs. 6/60 symptoms (see Figure 2). Seven of the nine new symptoms (not reported on Aug. 2) were among 16 adverse events listed for pirfenidone on the manufacturer’s website (see Figure 3). These included weight loss, anorexia, unusual fatigue, abdominal pain, indigestion, heartburn and insomnia (see Figure 2).

The rheumatologist advised discontinuation of pirfenidone, reinstatement of 10 mg/day of prednisone and remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring two and five days later, with a plan for a face-to-face visit if no improvement was apparent. Five days later, his RAPID3 had improved from 19.5/30 to 8/30 and his fatigue score improved from 9/10 to 4/10 (see Figure 2).

Weekly remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring was instituted, which documented clinical improvement according to RAPID3 and resolution of most pirfenidone-related symptoms over the next 10 weeks (see Figure 2).

A brief retrial of pirfenidone was followed by an increase of the RAPID3 score to 6.0 and was discontinued in a timely manner (see Figure 2, opposite). On Dec. 28 (after methotrexate was reinstated), the patient’s RAPID3 was 4.2/30, his fatigue score was 2.0/10, and he reported 6/60 symptoms.

Discussion

In this report, we present three new applications of the MDHAQ. First, RAPID3 documented substantial improvement over six months in a patient with a non-rheumatic disease, pulmonary fibrosis, based on usual routine MDHAQ completion in the clinic waiting area. RAPID3 may be useful in many non-rheumatic diseases. All ambulatory individuals wish to be as functional and pain free as possible and experience overall well-being, reflecting the three RAPID3 components, which are identical to the RA core data set.

Second, a remote electronic MDHAQ documented adverse events to a medication, pirfenidone, as substantially elevated RAPID3 and fatigue VNS scores, and seven new specific symptoms (see Figure 2, opposite) which were listed as adverse events for pirfenidone (see Figure 3, above right). A face-to-face visit did not appear mandatory, because he reported an unchanged pulmonary situation and virtually all new symptoms could be attributed to the pirfenidone (and possible withdrawal from low-dose prednisone and methotrexate). Discontinuation of pirfenidone, reinstatement of 10 mg prednisone, contact if symptoms were worsening and remote electronic MDHAQ review two days later appeared reasonable to avoid further acute stress to an elderly patient who required continuous oxygen therapy. Clear improvement two and five days later were documented on the remote electronic MDHAQ symptom checklist, which would not have been available if only RAPID3 were queried.

Third, weekly remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring was effective to document clinical improvement according to RAPID3 and resolution of many symptoms according to the MDHAQ symptom checklist over 12 weeks, between Sept. 24 and Dec. 28 (see Figure 2, opposite).

Remote electronic monitoring cannot be applied to all patients. The patient in this case was highly intelligent and reliable, and a plan for a face-to-face visit if his clinical status worsened seemed reasonable. Weekly remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring could be a useful screening procedure for many (but not all) patients. Completion of a weekly electronic MDHAQ was estimated by the patient to involve about 10 minutes, or a total of two hours over 12 weeks, less than the door-to-door time required for a single face-to-face clinic visit.

The flow sheet of MDHAQ data available to the rheumatologist had considerable relevant information about the patient, perhaps as much or more than other doctors who conducted face-to-face visits without MDHAQ data. Nonetheless, no reimbursement to the rheumatologist was possible for weekly contact with the patient—sometimes with telephone feedback and sometimes with no feedback when it appeared unnecessary. Perhaps new payment procedures may be proposed in the future for improved management strategies that don’t involve face-to-face visits.

Note: The remote electronic MDHAQ monitoring was not conducted through the electronic medical record (EMR), but using software for which certification is pending. The patient was instructed not to include private medical information (e.g., name, date of birth, medical record number) on the remote MDHAQ used in his care. Having all patient care information in one EMR would appear to be optimal, but the many administrative complexities and limitations of the EMR may render this difficult and detract from optimal patient care.17 Summary information and the flow sheet were entered into the EMR as PDF files, which may have required less time than manipulating the EMR to incorporate the information.

Adverse events to medications are reported to be associated with 5% of U.S. hospital admissions, 10% in the elderly.18 Systematic remote electronic questionnaires appear cost effective and broadly acceptable to patients with cancer, diabetes, and pulmonary and psychiatric diseases.19 A recent report indicated timely recognition of adverse events in oncology patients using remote electronic monitoring of symptoms.20 Remote, weekly MDHAQ monitoring as a routine procedure for patients who initiate high-risk medications could proactively alert clinicians to early recognition of adverse events, including the possible need for a face-to-face visit, overcoming a current requirement for a telephone or “My Chart” contact or awaiting report by the patient at the next visit. This strategy could help reduce the high prevalence, morbidity and mortality of adverse events in current medical care.

Juan Schmukler, MD, is a staff rheumatologist at Mount Sinai Hospital, Chicago. He previously served as chief medical resident at the John H. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, from 2015–16 and as a fellow in rheumatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, from 2016–18.

Juan Schmukler, MD, is a staff rheumatologist at Mount Sinai Hospital, Chicago. He previously served as chief medical resident at the John H. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, from 2015–16 and as a fellow in rheumatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, from 2016–18.

Theodore Pincus, MD, is a professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Theodore Pincus, MD, is a professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Disclosure

Dr. Pincus is president of Medical History Services LLC and holds a copyright and trademark on MDHAQ and RAPID3, for which he receives royalties and license fees, all of which are used to support further development of quantitative questionnaire measurements for patients and doctors in clinical rheumatology care.

Ethics & Consent

The Rush University Institutional Review Board waived a requirement for patient consent in completion of patient questionnaires, because the questionnaire is a component of routine care, analogous to laboratory tests, for quantitative data to guide clinical decisions.

References

- Castrejón I, McCollum L, Tanriover MD, Pincus T. Importance of patient history and physical examination in rheumatoid arthritis compared to other chronic diseases: Results of a physician survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Aug;64(8):1250–1255.

- Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med. 1968 Mar 21;278(12):652–657 concl.

- Pincus T, Castrejón I. Are patient self-report questionnaires as ‘scientific’ as biomarkers in ‘treat-to-target’ and prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis? Cur Pharm Des. 2015;21(2):241–256.

- Pincus T, Sokka T, Kautiainen H. Further development of a physical function scale on a MDHAQ for standard care of patients with rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2005 Aug;32(8):1432–1439. [Erratum in J Rheumatol. 2005 Nov;32(11):2280.]

- Pincus T. Pain, function, and RAPID scores: Vital signs in chronic diseases, analogous to pulse and temperature in acute diseases and blood pressure and cholesterol in long-term health. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66(2):155–165.

- Pincus T, Bergman MJ, Yazici Y. RAPID3-an index of physical function, pain, and global status as ‘vital signs’ to improve care for people with chronic rheumatic diseases. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2009;67(2):211–225.

- Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May;64(5):640–647.

- Curtis JR, Chen L, Danila MI, et al. Routine use of quantitative disease activity measurements among US rheumatologists: Implications for treat-to-target management strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018 Jan; 45(1):40–44.

- Pincus T, Castrejón I. MDHAQ/RAPID3 scores: Quantitative patient history data in a standardized ‘scientific’ format for optimal assessment of patient status and quality of care in rheumatic diseases. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(3):201–214.

- Castrejón I, Nikiphorou E, Jain R, et al. Assessment of fatigue in routine care on a Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ): A cross-sectional study of associations with RAPID3 and other variables in different rheumatic diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 Sept–Oct;34(5):901–909.

- Stucki G, Liang MH, Stucki S, et al. A self-administered rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index (RADAI) for epidemiologic research. Psychometric properties and correlation with parameters of disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Jun;38(6):795–798.

- Castrejón I, Yazici Y, Pincus T. Patient self-report RADAI (Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index) joint counts on an MDHAQ (Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire) in usual care of consecutive patients with rheumatic diseases other than rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013 Feb;65(2):288–293.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: A modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011 Jun;38(6):1113–1122.

- Schmukler J, Jamal S, Castrejón I, et al. Fibromyalgia assessment screening tools (FAST) based on only multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) scores as clues to fibromyalgia. ACR Open Rheumatology. 2019.

- Gibson KA, Castrejón I, Descallar J, Pincus T. Fibromyalgia Assessment Screening Tool (FAST): Clues to fibromyalgia on a multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) for routine care. J Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 1. pii: jrheum.190277.

- King TE Jr., Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2083–2092. [Erratum in N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1172.]

- Wachter RM. The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015. xv, 330.

- Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):

1556–1564. - Johansen MA, Henriksen E, Horsch A, et al. Electronic symptom reporting between patient and provider for improved health care service quality: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. part 1: State of the art. J Med Internet Res. 2012 Sep–Oct;14(5):e118.

- Basch E, Pugh SL, Dueck AC, et al. Feasibility of patient reporting of symptomatic adverse events via the patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) in a chemoradiotherapy cooperative group multicenter clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017 Jun 1;98(2):409–418.

- Pincus T, Swearingen C, Wolfe F. Toward a multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ): Assessment of advanced activities of daily living and psychological status in the patient-friendly health assessment questionnaire format. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Oct;42(10):2220–2230.