Temporal arteritis was first described by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson in 1890 in an elderly retired gentleman’s servant who developed red, painful streaks on his temples and was found to have bilaterally swollen temporal arteries with feeble pulses.1 Sir Hutchinson disputed the suggestion that the red streaks were caused by the man’s hat and, instead, called his observation, albeit without histology, “an unquestionable example of an arteritis, which spread along the affected vessels, causing swelling of the external coats and adjacent cellular tissue which resulted very quickly in occlusion of the vessels.”

Temporal arteritis is a form of the medium to large vessel arteritis named giant cell arteritis.

Pathology

More than a century has passed since this initial observation, but the sequence of events precipitating the arteritis remains unclear.

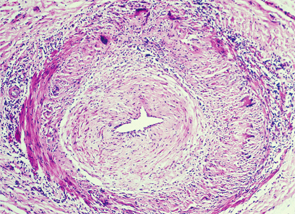

Temporal arteritis is now recognized to be a form of the medium- to large-vessel arteritis named giant cell arteritis (GCA) because of characteristic giant cells seen on histology. In addition to branches of the external carotid artery, GCA can affect many other vascular territories, including the ophthalmic artery, causing vision loss in 10–15% of patients; the vertebrobasilar arteries, causing ischemic stroke; the aorta, causing dissection or aneurysm formation; and the subclavian arteries, causing claudication.2,3 The temporal artery biopsy typically demonstrates mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates in the vessel wall, with fragmentation of the elastic lamina. The lumen is often occluded from intimal hyperplasia. Giant cells, when found, are found at the intima-media border.4

There may be an association between VZV & GCA rather than causation.

GCA Trigger

The pathologic features, however, don’t provide an etiology. In the May 12, 2015, issue of Neurology, Don Gilden, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and colleagues published provocative evidence that varicella zoster virus (VZV) may trigger GCA.5 They examined 82 formalin-fixed biopsy specimens of histologically confirmed GCA along with 13 cadaveric temporal artery controls. Strikingly, immunohistochemical analysis of the arterial wall for VZV gE antigen (produced in infected cells) was positive in 74% of the GCA cases compared with only one positive finding in the control arteries. As is characteristic of GCA pathology, there were “skip areas” where VZV was absent. GCA pathology in 89% of cases tended to be adjacent to regions containing the VZV antigen. In almost half of the cases, the VZV antigen was found in the adventitia of the arterial wall.

The authors confirmed the immunohistochemical findings using other techniques, as well. VZV DNA was detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 40% of the lesions that were positive using immunohistochemistry. Electron microscopy on a single specimen showed enveloped viral particles within the vessel wall.