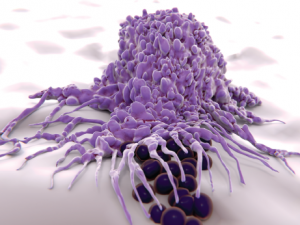

Macrophages engulf and digest cellular debris and pathogens.

Juan Gaertner / shutterstock.com

MADRID—Research into pharmacodynamic biomarkers has shown that macrophages may have an important role in the pathogenesis of several diseases, including systemic sclerosis, an expert said at the 2017 Annual European Congress on Rheumatology (EULAR). The findings were discussed in a session that also covered how an understanding of M1 macrophages’ role in fibrosis has evolved from kidney research.

Robert Lafyatis, MD, director of the University of Pittsburgh Scleroderma Center, said that when his lab has looked at genes implicated in a variety of diseases, genes related to macrophages have figured prominently over and over again.

Researchers took skin biopsies from the forearm and looked at genes that correlated with the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) for the whole body. In addition to the types of genes they expected to find, researchers saw that macrophage-related genes were clustered together, highly correlated with the mRSS. “That’s what made us think that macrophages may be important to skin diseases, [such as] systemic sclerosis,” Dr. Lafyatis said.

When researchers tracked data over time, they found that as the skin score worsened, expression of these genes—including thrombospondin-1 and MS4A4A—was increased. It was a longitudinal biomarker they found so reliable that it’s now used in clinical trials.

They’ve also looked at tocilizumab trial data from patients receiving placebo and found that macrophage-related genes were linked to changes in a patient’s skin score. “Macrophage markers appear prominently in our pharmacodynamics biomarkers [and] in our prognostic biomarkers,” Dr. Lafyatis said. “In other words, the number or some quality of macrophages seems to be an important predictor, if you will, of whether somebody’s going to develop progressive skin disease.”

The expression of these genes is also correlated with systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease, researchers found.

‘Metabolism is relevant in understanding how macrophages work,’ Dr. Camara said.

“From several different standpoints—skin disease, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension—we see this recurrent theme of macrophages somehow having an important role in pathogenesis—or at least the most obvious role,” he said. However, what activates them remains unclear.

“There are lots of different kinds of macrophages and dendritic cells in different sites,” Dr. Lafyatis said. “They’re different at different sites. They’re different when they start, and then they’re going to change. That’s one of the questions: How do they change as you have disease come on? All of these things are difficult questions to answer.”

His lab is now using single-cell RNA sequencing to further explore what’s happening in the cells. “We’ve taken the approach of examining the total cellular heterogeneity of the tissues, trying to characterize the various cellular subpopulations and define marker genes,” he said.

Fibrosis

Niels Camara, PhD, associate professor of immunology at the University of Sao Paolo in Brazil, described insight his lab has made into the role of M1 macrophages in fibrosis of the kidney.1 Researchers found that animals subjected to ischemia suffer a large amount of apoptosis and necrosis, but with the infiltration of cells relatively mild. After seven days, the animals fully recovered.

“Six to eight weeks later, you can see an infiltration of macrophages and also deposition of collagen,” Dr. Camara said. “So we know this happens because of inflammation. Inflammation is the big link between an acute and chronic injury.”

Researchers homed in on the role of M1 macrophages, which are distinct from M2 macrophages in appearance, what they do and how they perceive their microenvironment, he said. “Normally, when you induce a disease in an animal model, what you see is a chronic and sustained inflammation—the degree of inflammation is low as time passes, and you also see [depending on the model] the presence of M1 macrophages. That’s why we believe that M1 macrophages could very well be inducing fibrosis,” Dr. Camara said.

They set out to find out what drives this infiltration. They found that macrophages in the hypoxic conditions that are frequent in the kidney lead to the release of uric acid. “If I put macrophages under hypoxic conditions, 24 hours is already enough to see an increase in uric acid” in wild-type mice, Dr. Camara said.

Crystals from uric acid can activate the inflammasome, previous studies have found. But his lab found that the soluble form of uric acid in their experiments also has this effect.

The inflammasome is related to the metabolic control of the cells, and M1 macrophages seem to have effects through metabolic pathways as well, he said.2

“Metabolism is relevant in understanding how macrophages work,” Dr. Camara said. “M1 macrophages are related to fibrosis through activation of the inflammation of the inflammasome and the metabolism.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

References

- Camara NOS. Macrophages, metabolism and inflammation (abstract SP0105). Annual European Congress of Rheumatology. 2017 Jun 15. Madrid, Spain.

- Moon JS, Hisata S, Park MA, et al. mTORC1-Induced HK1-dependent glycolysis regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Rep. 2015 Jul 7;12(1):102–115.