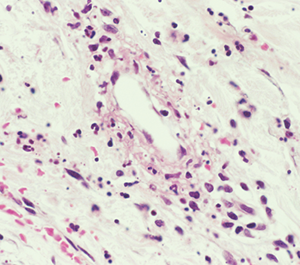

Biophoto Associates / Science Source

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Experts speaking at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting session, Update on Small-Vessel Vasculitis, offered insight into the latest approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases involving the inflammation of blood vessels.

“Vasculitis is an immune-mediated process. White blood cells invade the vessel wall, causing inflammation throughout the vessel wall,” said Jason M. Springer, MD, MS, director of the Vasculitis Clinic at Kansas University Medical Center in Kansas City, Kans. Occlusion of the vessels may affect downflow of blood to tissues, which then necrotize.

Although types of vasculitis are divided by the sizes of vessels involved—small, medium, or large—“this isn’t a perfect system,” Dr. Springer said.1 “There’s a lot of overlap in terms of the sizes of blood vessels involved in these diseases. Some forms of vasculitis don’t follow the rules.” Vasculitis may be either a primary or secondary disease, and rheumatologists must also rule out vasculitis mimics, including antiphospholipid syndrome and atherosclerosis.

Eponyms Are Out

Traditional eponyms for the small-vessel vasculitides are now out of style, said Dr. Springer. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly called Wegener’s granulomatosis) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss disease). Immune complex vasculitis, in which immunoglobulins and complements form complexes that can deposit in vessel walls, includes cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV) and IgA vasculitis (formerly Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

No current diagnostic criteria exist for vasculitis. The Modified ACR Classification Criteria for vasculitides were published in 1990, and do not reflect current diagnostic tests or disease definitions, he said. Classification criteria are meant to identify already-diagnosed patients for clinical trials, not for clinical diagnosis. New diagnostic and classification criteria in vasculitis are now being developed by investigators who presented an early draft of their GPA criteria at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. The 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions of vasculitides provide one way to distinguish these diseases from others.2

Diagnosis is based on clinical features, biopsy and testing for ANCA antibodies.

“Just because the ANCAs are negative, don’t rule out these types of vasculitides,” said Dr. Springer.

With indirect immunofluorescence, c-ANCA antibodies tend to stain diffusely in the cytoplasm of the neutrophils, and p-ANCA stains around the nucleus. ELISA or EIA assay tests identify enzyme targets within the neutrophils, such as PR3-ANCA or MPO-ANCA. Look for antibody test results that correlate; the majority of GPA patients have a c-ANCA with a PR3-ANCA pattern, and most MPA patients show p-ANCA with MPO-ANCA. Although some patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis have unusual antibody patterns, this may be a sign to look for another diagnosis, Dr. Springer noted.

GPA

GPA is ANCA positive in 80–90% of cases, said Dr. Springer. It is characterized by granulomas and often affects organ combinations, especially the kidneys, lungs and ears, nose and throat (ENT).3 GPA patients may have a bloody, crusting nose and sinusitis that doesn’t respond to antibiotics.

“The inflammation can be intense enough to lead to a collapse of the nasal bridge,” known as saddle nose, he said. “It’s a gradual process and can take years to progress. Patients may not even notice the change.”

Other GPA symptoms include strawberry gingiva sores, subglottic stenosis, and granulomas that develop in the back of the eyes, causing double vision. GPA may also cause bleeding in the lungs from inflammation of the alveoli.4

“This will be a very dramatic presentation. They will be out of breath very quickly and even coughing up blood,” Dr. Springer said. Kidney involvement will not produce noticeable symptoms until the disease is very advanced. On urinalysis, look for red blood cell casts in the urine. GPA patients may present with a dropped hand or foot caused by mononeuritis multiplex, joint pain without swelling, stomach pain after eating or blood in the stool, he said.

Conditions Can Be Similar

MPA is a necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits that mostly affects the small vessels, with glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis as common problems, said Dr. Springer. Like GPA, it is ANCA positive in 80–90% of cases, and may be accompanied by alveolar hemorrhage, renal failure, and skin, peripheral nervous system or gastrointestinal system involvement.

“Some people have questioned [whether] these two diseases, because they have so many similar features, are a spectrum of the same disease, but they seem to have distinct genetic features,” said Dr. Springer.5 Unlike GPA, MPA has no ENT involvement or granulomas, and fewer relapses.

EGPA is an eosinophil-rich, necrotizing, granulomatous inflammation that often affects the small to medium vessels of the respiratory tract.6 It is associated with asthma and eosinophilia, said Dr. Springer.

EGPA has three phases that may overlap. Patients may first have allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, sinusitis or asthma. In the second phase, high amounts of eosinophils may invade tissue, particularly the lungs. This causes eosinophilia, often accompanied by pulmonary infiltrates. The third stage involves systemic vasculitis manifestations, he said.

EGPA is ANCA positive in about 40–50% of cases, and more frequently when there is kidney involvement, said Dr. Springer.7 ANCA-positive patients are more likely to have glomerulonephritis and mononeuritis multiplex, and ANCA-negative patients are more likely to have cardiac involvement.

Notable Clues

When should rheumatologists suspect ANCA-associated vasculitis? If a patient has palpable purpura, mononeuritis multiplex or pulmonary-renal syndrome, such as bleeding in the lungs and glomerulonephritis, although other diseases may have these manifestations, too, said Dr. Springer. Basic diagnostic work-up, urinalysis with microscopy to look for red blood cell casts, ANCA testing and lung imaging, preferably computed tomography scan to spot granulomas, should be done, he said.

Treatment starts with an induction phase to prevent organ damage and control inflammation using cyclophosphamide, rituximab or methotrexate. Maintenance therapy’s goals are to prevent relapse and improve quality of life with methotrexate, azathioprine, rituximab and, as a second-line therapy, mycophenolate. Patients will taper glucocorticoids in the background in addition to their disease-modifying therapies. Remission is no active disease, although it can be hard to spot if there is tissue damage, he said.

Small-vessel vasculitis may not produce noticeable symptoms for years, said Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Vasculitis Care and Research at the Cleveland Clinic. They may present with a palpable, purpuric rash, usually on the legs. Biopsy on a new rash or the periphery of the rash is preferable.

Secondary Disease

When vasculitis is secondary, the underlying cause may be difficult to identify and treat, she said. Secondary vasculitis may be caused by viral infections, such as polyarteritis nodosa from hepatitis B and CV from hepatitis C (HCV), as well as vasculitis caused by cancer, systemic diseases or as a medication side effect.8 Rashes may be mistaken for allergic reactions until biopsy shows vasculitis signs, she said.

“Diagnosis is difficult in the early stages,” said Dr. Villa-Forte. Multisystem disease is one clue to suspect secondary vasculitis, especially kidney, polyneuropathic, skin or musculoskeletal involvement. “The onset of these diseases is usually subacute,” she added. “Usually, your patient doesn’t pay attention to the preceding symptoms, so you have to ask questions.”

Symptoms of secondary vasculitis may be frequent, but nonspecific and constitutional, such as fevers, weight loss or malaise, as well as arthralgia and myalgia, she said. Patients may have these symptoms for months before they seek attention.

‘There’s a lot of overlap in terms of the sizes of blood vessels involved in these diseases. Some forms of vasculitis don’t follow the rules.’ —Dr. Springer

Although not a gold standard for secondary vasculitis diagnosis, biopsy may help diagnosis, ideally on the edges of a skin lesion within 48 hours of its appearance, said Dr. Villa-Forte. It may be hard to find an accessible place to biopsy if patients have skin lesions.

“Biopsy may show us inflammation of blood vessels, but not give us any clues as to the type of vasculitis we are dealing with,” she said. Laboratory testing should be based on clinical suspicions, but do not delay diagnosis because a patient’s creatinine results are normal, she said.

Where Rheumatologists Come In

When rheumatologists see patients with CV, successful treatment of the HCV infection may get rid of the vasculitis, said Dr. Villa-Forte. Patients with severe vasculitis may need prednisone with or without rituximab, or plasmapheresis if organs or life are threatened, she said.

Although not common, some systemic diseases may cause secondary vasculitis, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome and dermatomyositis.

IgA vasculitis can be either primary or secondary, seems to be linked to infection and predominantly affects small vessels of the skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract and kidneys, she said. Often, patients have skin purpura and joint arthralgia.

“It’s the most common vasculitis in childhood, but it is rare in adults,” said Dr. Villa-Forte. “In children, it seems to have a seasonal pattern, more common in fall and winter, so it’s been linked to upper respiratory infections.” Adults with IgA vasculitis have worse renal outcomes, and the disease doesn’t seem to spontaneously remit as often as it does in children, she said.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta.

Miss Any of These Important Sessions?

If you missed any of these important sessions, find them on SessionSelect.

References

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Hoffman GS, Weyand CM, Langford CA, et al. Inflammatory diseases of blood vessels, second edition. Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. Published online 3 May 2012.

- Ananthakrishnan L, Sharma N, Kanne JP. Wegener’s granulomatosis in the chest: high-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Mar;192:676–682.

- Lyons PA, Rayner TF, Trivedi S, et al. Genetically distinct subsets between ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 19;367(3):214–223.

- Lanham JG, Elkon KB, Pusey CD. Systemic vasculitis with asthma and eosinophilia: A clinical approach to the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984 Mar;63(2):65–81.

- Sinico RA, di Toma, L, Maggiore U, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2926–2935.

- Vassilopoulos D, Younossi ZM, Hadziyannis E, et al. Study of host and virological factors of patients with chronic HCV infection and associated laboratory or clinical autoimmune manifestations. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(suppl 32):S100–S111.