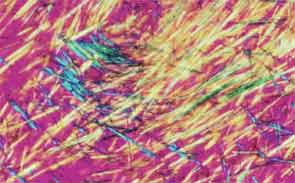

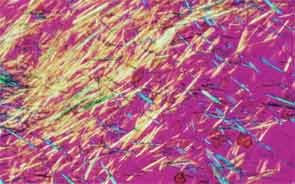

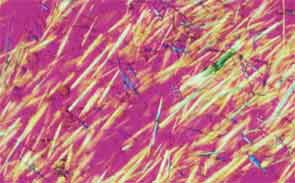

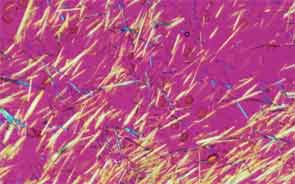

SAN DIEGO—Microscopic crystals can deposit in joints and contribute to painful inflammation in arthropathies like gout as well as osteoarthritis (OA). Gout affects as many as six to eight million adults, and OA strikes around 27 million adults in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 Prevalence of these diseases is expected to rise even higher as the older population increases. New research offers clarity on the role crystals play in inflammation and what potential therapies may treat patients more effectively. A panel of global rheumatologists addressed these topics at the 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.]

Rheumatologists don’t yet have a clear vision of why monosodium urate (MSU) crystals form in certain joints in gout, said Nicola Dalbeth, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. More accurate imaging technologies, especially ultrasonography and dual-energy computed tomography (DECT), may help understand the crystals’ impact in joints, she said. “Conventional CT is very good for assessing bone damage in gout,” Dr. Dalbeth noted. Conventional CT may be used to understand the relationship between erosions and tophi, and tophi may be seen as infiltrating and filling up the joint space in gout cases. Of her recent research of patients with tophaceous gout, Dr. Dalbeth noted, “We saw very close relationships between erosion scores and the size of tophi.”

DECT may be used to measure the urate burden in gout patients and visualize the crystals in a tophus, Dr. Dalbeth said. “Dual-energy CT shows us that the composition of a tophus is quite variable,” she noted. Additionally, DECT shows how MSU crystals can affect the soft tissues of the joint, Dr. Dalbeth said. “These imaging modalities have really highlighted the involvement of tendons in gout,” particularly the Achilles and peroneal tendons, both in the enthesis and body of the tendon, she said.

Microscopic examination of cells within tophi in gout patients reveals a large number of CD68+ cells in the corona zone surrounding the deposits of MSU crystals, as well as cells expressing interleukin (IL) 1ß and transforming growth factor ß-1. These cells may all contribute to the cycle of inflammation in gout. Osteoclasts are also implicated in bone damage in gout, Dr. Dalbeth said. At erosion sites, numerous osteoclast-like cells are found, and enhanced osteoclastogenesis occurs through an interaction of the MSU crystals with stromal cells, she added. RANKL-expressing T cells are also found in the corona zone in tophi, and are related to osteoclast formation. MSU crystals lead to reduced bone formation and then localized bone erosion, she summarized.

All of this new information suggests that targeting osteoclast formation or urate deposition are potential therapeutic options for joint damage in gout, Dr. Dalbeth said. Current studies are examining anti-osteoclast therapy for prevention of bone erosion, she noted. In addition, targeting urate crystals through intensive urate-lowering therapy may prevent development of joint damage or promote healing of bone erosion.

More research is needed on the pathogenesis of gout to identify what early signs point to the development of joint damage, she said. “Can we predict what patients will develop severe joint damage other than those who develop tophi? Not yet,” she said.

Limit Gouty Inflammation

The new frontier of gout research is finding ways to limit inflammation and connective tissue destruction by tophaceous disease, said Robert Terkeltaub, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Two important points to note in cases of gouty arthritis with “roaring inflammation” are that urate crystal deposits often are quiescent and that acute gout usually is self-limited, Dr. Terkeltaub said. Even in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia, crystals form in about 25% of cases. MSU crystals may “quietly activate chondrocytes, and gout damage may start with superficial zone chondrocytes,” he added.

To understand what can limit gouty inflammation, it’s important to explore how it may be activated in these cases, Dr. Terkeltaub said. In gout, the NLRP3 inflammasome activation of IL-1 beta secretion is at the root of inflammation. This may be one clue to why gout prevalence is very high in the elderly population. “It has become apparent that aging is a heightened state of NLRP3 activation,” he added. Adaptive immunity may limit NLRP3-mediated, acute inflammation, however.

Nutrition has always played a central role in gout management. In fact, dietary substances may either inhibit or activate the inflammatory responses in gout, Dr. Terkeltaub said. Fish oil may contribute to the inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome and blunts the activation of NLRP3, he noted, and this action may merit further testing of fish oil supplements in both gout and recent-onset RA. “Fish oil may dampen at least the IL-1 pathway in a number of inflammatory arthropathies,” he said. Consuming low-fat dairy products, which have a low purine content and have been shown to have urate-lowering effects, also may help lower the risk of developing gout in the first place, he said.

Metabolic super-regulation by caloric restriction and pharmacologic interventions also appears to limit gouty inflammation, he said, as is the “clearing out the garbage” by M2b and M2c macrophages by achieving efferocytosis. Understanding these processes in gout will point to the development of new therapies, including IL-1 and IL-6 antagonists, NLRP3-pathway inhibitors, drugs that interface between nutrition status and inflammation, and dietary interventions or fish oil supplements, Dr. Terkeltaub concluded.

Contributions to OA

In addition to gout, non-urate, calcium-containing crystals can induce inflammation and aggravate OA, a disease where 30% to 60% of patients have these crystals in their joint fluid, said Geraldine McCarthy, MD, clinical professor and consultant rheumatologist at University College Dublin in Ireland. “Calcium-containing crystals contribute to cartilage damage through multiple mechanisms in osteoarthritis,” she noted. Calcium pyrophosphate [CPP] crystals likely contribute to cartilage degradation and synovitis in OA, and also likely play a central role in pseudogout. “Small CPP crystals are more inflammatory than larger ones,” she said.” Basic calcium phosphate (BCP) crystals also are found in OA, but are difficult to identify because they are ultramicroscopic. When these crystals were injected into murine knee joints, they led to synovial inflammation and cartilage degradation. BCP can induce mitogenesis and stimulate COX-1 and COX-2, prostaglandin production, and cytokine production, particularly IL-1 and IL-18, Dr. McCarthy said. “BCP crystals may be every bit as potent as MSU crystals” in their ability to produce matrix degradating enzymes in joints, she said.

Basic calcium phosphate injections into joints have been shown to increase serum levels of the alarmin S100a8, for example, which can stimulate the activation of toll-like receptors in response. This process can in turn lead to the production of IL-1, Dr. McCarthy noted. “BCP plays an important role in the pathogenesis of OA,” she said, and in turn, the associated synovial inflammation may lead to more crystal formation.

More accurate tests for BCP crystals in synovial fluid are needed, Dr. McCarthy said, and “we need to understand that the complexity of OA requires heterogeneity of treatment.” Colchicine may be used to help control crystal-induced flares, but neuromuscular complications are a concern, she said, and colchicine trials in OA have shown limited benefit. The current evidence suggests a connection between OA severity and crystal activity in the joints, she added, but future research may lead to therapies to break that vicious crystal–inflammation cycle.

Susan Bernstein is a writer based in Atlanta.