Sarah2 / shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Ken Smith, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Cambridge, England, gave an update on anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

Although vasculitis tends to be defined first by vessel size, the clinical differentiation between the forms is not reliable, explained Dr. Smith. For example, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) are often treated as a single disease in clinical trials, but in truth they have different clinical features and two different autoantibody reactivities that correlate well, but not perfectly, with classification as GPA or MPA.

Clinicians have long noticed that patients with AAV exhibited familial clustering, like that seen with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These observations led to the identification of many candidate genes, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have allowed for the statistical association between disease and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These results, published in 2012, confirmed that AAV has a genetic component.1

The researchers also found genetic distinctions between GPA and MPA that are more strongly associated with ANCA specificity than with the clinical syndrome and imply the response to the autoantigen proteinase 3 (PR3) is a central pathogenic feature of PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis. This study that provided preliminary support for the hypothesis that PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis and myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA-associated vasculitis are distinct autoimmune syndromes.

New Data

The recognition of the significant genetic contribution to AAV prompted a more detailed analysis, which yielded three main variants: HLA class II, SERPINA1 and PRTN3, each of which was specifically associated with PR3-ANCA.2 Both the HLA and non-HLA gene variants appear to alter proteins integral to immune responses that likely play key roles in the pathogenesis of AAV.

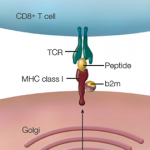

In particular, the largest effect on risk came from a triallellic HLA-DPB1 haplotype, meaning that three gene variants are inherited together. The resulting change in amino acid sequence affects a β-chain polymorphism in the HLA-DP antigen-binding pocket that modifies the protein’s peptide-binding properties and, therefore—possibly—T cell allorecognition. The analyses suggest there is only a single genetic association with the HLA region, and so the other SNPs identified in the region (e.g., collagen) are likely associated by virtue of linkage disequilibrium.

The two other loci related to AAV code for a serine protease inhibitor (serpin), which appears to control key intracellular and extracellular pathways of the auto-antigen PR3.3 New research suggests free PR3 may be more antigenic than complexed PR3, signifying that its role in autoimmunity may be more complicated than originally believed. These nuances can be further explored, because researchers published the genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome, which has expanded the ability to use specific proteins to link genetic factors to diseases.4 The evolving analyses support patient stratification based on ANCA specificity.

Researchers have used the accumulated data to determine why MPO- and PR3-AAV have so many clinical similarities. One hypothesis is that the various forms of ANCA have a common target (neutrophils) and the damage to the neutrophils results in a common clinical manifestation. “It could be a sort of antigenic accident,” explained Dr. Smith. If this is true, then it may be that the balance between costimulatory and coinhibitory signals shape T cell exhaustion and determine whether the immune system becomes autoreactive.5