What do rheumatologists consider to be fibromyalgia when they diagnose it in practice? Answering this question was the basis for the “ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity,” published in May 2010.1

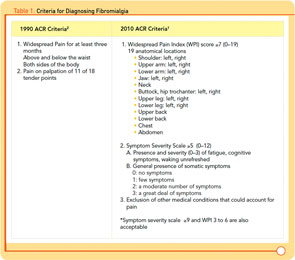

The 2010 criteria build upon—but do not replace—the “ACR 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee,” which were written as classification criteria and not clinical diagnostic criteria.2 Advances in the understanding of fibromyalgia and concerns about how the 1990 criteria functioned for fibromyalgia diagnosis prompted the investigators to revisit the issue and create the 2010 criteria, which the ACR endorsed.

In addition to developing diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia that are in line with the way the disease was being identified by rheumatologists, the authors of the 2010 criteria hope that the guide will facilitate diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia by primary care physicians.

The Rheumatologist recently spoke with several fibromyalgia experts about the process of developing the 2010 criteria and how the new criteria are being received and implemented, both within and outside of the rheumatology community.

Another Look at Fibromyalgia

In 2008, several members of the 1990 fibromyalgia criteria committee began discussing efforts to revise the criteria. Two years after those conversations, the project was complete with participation from 113 ACR members and 893 patients in the key study.

Regarding the speed of the effort, “that’s all Fred Wolfe,” jokes Don Goldenberg, MD, chief rheumatologist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. A member of the 1990 and 2010 fibromyalgia criteria committees, Dr. Goldenberg was key in engaging Dr. Wolfe in the revision effort, because Dr. Wolfe had distanced himself professionally from fibromyalgia.

This consensus-based approach, with the study performed in community rheumatology clinics, was a departure and reflects lessons learned from the 1990 fibromyalgia criteria. “Unfortunately, the 1990 committee, myself included, had a singular idea about fibromyalgia, which may be have been incorrect,” concedes Frederick Wolfe, MD, leader of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases in Wichita, Kan., and lead author for both the 1990 and 2010 fibromyalgia criteria sets. “The 1990 ACR fibromyalgia committee believed in the Smythe and Modolfsky definition for fibromyalgia with widespread pain, lots of tender points, fatigue, and unrefreshed sleep.” The study testing the 1990 criteria was designed to support the expert opinion; hence the tender point criteria and widespread pain became the most specific factors and defined the criteria. “The 1990 criteria was the most circular thing we have done,” says Dr. Wolfe.

For the 2010 criteria, 113 rheumatologists identified fibromyalgia patients in their clinic who had been diagnosed previously by them. Those patients were not required to meet the 1990 criteria to be included. The requirement was that patients were diagnosed with fibromyalgia, even if the diagnosis was based on symptom complaints rather than physical findings.

The committee also considered how to categorize and assess patients with fibromyalgia whose symptoms improved so that they no longer met the 1990 criteria. They added a symptom severity scale in the 2010 criteria as a tool to quantify the symptoms of these patients over time and to differentiate among patients according to the level of fibromyalgia symptoms. Cognitive impairment, fatigue, and waking unrefreshed, along with the degree of general somatic complaints, comprise the symptom severity scale. Additionally, the 2010 fibromyalgia criteria include the widespread pain index score based on presence of pain at 19 anatomical sites and excluding other causes of widespread pain.

Rationale for Revision

Three realities drove the need to revise the ACR fibromyalgia criteria. First, there was the way the 1990 criteria, which were intended for classification and not diagnosis, were being applied in general practice. More problematic was that people had mistakenly thought the tender point exam was the essence of the 1990 criteria. “The tender point exam is a proxy for the widespread hyperalgesia present in fibromyalgia. Somehow, that point never got through to clinicians,” says Dr. Goldenberg. “Patients are not bothered by tender points. The tender point exam did not emphasize the major features of fibromyalgia such as the extent of the pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, multiple somatic symptoms, and cognitive difficulties,” says Dr. Wolfe.

Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and 2010 fibromyalgia criteria committee member, notes, “no other syndrome required anything like tender points, a physical sign that had no impact on clinical outcomes.”

The third rationale was that the old criteria failed to allow for continuum and hetereogeneity in fibromyalgia presentation beyond pain. “If you have only 10 tender point points, are you really a healthy normal person?” says Dr. Wolfe.

“Memory problems and fatigue are a significant part of the illness, but the 1990 criteria failed to give them weight and only captured the pain element,” says Dr Clauw. Dr. Wolfe found in previous research that when tracking symptoms, patients vacillated between meeting and not meeting the 1990 criteria. In fact, in the 2010 criteria study, one in four patients did not meet the 1990 criteria. The actual level of symptoms was more important than whether or not patients satisfied the 1990 criteria. Hence, creating a symptom severity scale was the fourth major rationale revising the fibromyalgia criteria.

Personally important to Dr. Wolfe, the 2010 criteria accommodate a spectrum of beliefs regarding the legitimacy of fibromyalgia as a diagnosis. “The new criteria enable physicians who are uncomfortable with the socio-political aspect of fibromyalgia to evaluate patients without having to sign in as a full-time believer in fibromyalgia. Instead of saying, ‘We’re treating fibromyalgia,’ we have patients who have with high levels of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and body pain. We are treating those symptoms.”

Criticisms of the 2010 Criteria

The two primary criticisms of the revised criteria are the removal of the tender point exam and the exclusion of depression from the symptom severity scale. “The new criteria have been misconstrued as saying doctors no longer need to do a physical examination to diagnose fibromyalgia,” says Dr. Goldenberg. “In the 2010 criteria, we explicitly state the need rule out other conditions. In the old criteria, excluding other conditions was only implicitly stated. It’s impossible to determine if someone has a musculoskeletal disorder versus fibromyalgia without touching them. With the new criteria, what we are saying is that 11 of 18 tender points are not necessary to make an accurate diagnosis of fibromyalgia.”

Many in the rheumatology community were displeased at the exclusion of depression from the 2010 fibromyalgia criteria. “The reality is we don’t see happy, healthy people in rheumatology practice. High rates of depression are seen across all chronic diseases including osteoarthritis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis,” says Dr. Wolfe. “Depression was excluded because it didn’t improve the specificity for diagnosing fibromyalgia.”

Psychiatrists generally support the decision to exclude depression from fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. “Given [that] we’re focused on specificity over sensitivity, including depression would not help us to make a more accurate diagnosis for fibromyalgia,” says Rakesh Jain MD, MPH, practicing psychiatrist and clinical researcher from Lake Jackson, Texas. Although depression is not helpful in making an accurate fibromyalgia diagnosis, the committee widely acknowledges depression is still a significant clinical presentation for fibromyalgia. As Dr. Wolfe notes, “depression and fibromyalgia is a chicken–egg scenario. We cannot differentiate if depression is the result of fibromyalgia symptoms or if one cannot have fibromyalgia without depression.”

The tender point exam did not emphasize the major features of fibromyalgia such as the extent of the pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, multiple somatic symptoms, and cognitive difficulties.

Clinical Utility of the 2010 Criteria

The 2010 ACR criteria with the widespread pain index and symptom severity score have the clinical potential to serve as both a screening tool and a patient management tool. Dr. Clauw would like to see rheumatology and leaders in fibromyalgia position the new criteria as screening criteria for fibromyalgia. Specific to the rheumatology practice, screening is relevant for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and lupus, who have a higher prevalence of fibromyalgia.

The evolving picture around pain in rheumatic diseases, with multiple pain presentations, sleep disturbance, and depression, also warrants a generalized screening approach. “Rheumatologists, in the last couple years, are beginning to realize not all pain can be attributed to inflammation or damage in the periphery,” notes Dr. Clauw. “Patients often seek treatment for the one or two locations where the pain is more severe. If we don’t fully question patients about pain, we are missing the picture. We end up using peripherally targeted agents like antiinflammatory drugs and opioids without much success.” Using the fibromyalgia criteria as a general screening tool will help identify patients with types of pain that respond more to centrally activating agents like tricylic antidepressants, serotonin norepineprhine reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants.

The revised criteria, particularly with the symptom severity scale, lend themselves to use as a follow-up tool for assessing medical management. Dr. Wolfe notes, “When patients come to us, we should be asking, How is the pain?, How is the level of fatigue?, [and] How is your sleep?” The widespread pain index and symptom severity scale enable the tracking of pain symptoms longitudinally. These scales help compensate for the lack of objective clinical measures for fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia in Primary Care Settings

Another major driver for revising the fibromyalgia criteria is to help primary care physicians appropriately diagnose and manage fibromyalgia. “Most rheumatologists know how to diagnose fibromyalgia with or without the new criteria,” Dr. Goldenberg says. He feels that fibromyalgia patients should be managed predominately by primary care, with rheumatologists serving as consultants.

The rheumatologist shortage is also a factor in the drive to shift fibromyalgia diagnosis and management to primary care, Dr. Clauw believes. “Not enough rheumatologists exist to take care of all the fibromyalgia patients. We need to help primary care physicians be able to identify fibromyalgia in routine clinical practice since the long-term management requires medication and multidisciplinary treatment that primary care physicians can easily do,” he notes. Since rheumatologists are unable to offer anything for medical management unique from primary care, Dr. Clauw feels that rheumatologists’ expertise and time can be better leveraged in caring for patients with rheumatologic conditions that require immunosuppressant drugs.

Dr. Clauw advocates promoting a model in rheumatology to get all physicians outside the specialty to start using the 2010 diagnostic tools as screeners. In this model, when general medicine colleagues identify people with elevated scores on the questionnaire, rheumatologists would consult on the first five to 10 patients to confirm the fibromyalgia diagnosis, exclusion of other musculoskeletal conditions, and management plan. By initially assisting nonrheumatologists in getting comfortable diagnosing fibromyalgia, rheumatologists would encourage general medicine colleagues to rely less on rheumatology referrals for fibromyalgia.

Patients often seek treatment for the one or two locations where the pain is more severe. If we don’t fully question patients about pain, we are missing the picture.

Response Beyond the Rheumatology Community

Opportunity as well as resistance to change categorizes the response among the primary care and psychiatry communities. “The disadvantage of the new criteria: It’s a change in thinking and new way of diagnosing fibromyalgia,” says Shay Stanford, MD, assistant professor in the department of family medicine who sees fibromyalgia patients at the Women’s Health Research Program Treatment Center at the University of Cincinnati.

“People are still pondering the new criteria; they’re not quite sure if it’s an advancement or has further pushed the fibromyalgia issue backwards,” says Dr. Jain.

Both Drs. Jain and Stanford noted that the tender point exam helped patients accept their diagnosis. “When I did a tender point exam, for some reason in patients’ minds, fibromyalgia was a more acceptable diagnosis,” says Dr. Stanford. “Many patients want a definitive test and the tender point exam met that need. Whereas with the new criteria, many patients ask, is there a blood test or something?” Although the 2010 criteria do require a physician examination, there is no longer a specific number of tender points required for a positive diagnosis.

However, Dr. Stanford has adapted to the new criteria by explaining to patients the lack of a definitive test for fibromyalgia. She communicates that the widespread pain index and symptom severity score is a good diagnostic tool with a high degree of overlap with the tender point exam. “Communicating the severity symptom scale to patients will be valuable in giving patients a sense of where their personal disease is over the course of management,” says Dr. Stanford.

Outside rheumatology, the revised criteria are perceived as lowering barriers to fibromyalgia diagnosis. Dr. Jain says, “while I am great fan of the tender point exam since it helped me differentiate fibromyalgia from other conditions, I disliked the tender point criteria because so few clinicians were actually doing it. With the elimination of the tender point criteria, perhaps more patients will get diagnosed with fibromyalgia.”

Dr. Stanford also experienced problems with how tender point examinations were performed. She notes, “I get many patients saying, ‘I had a tender point exam.’ When I perform the exam, they say ‘That’s not what my doctor did.’ ” The new criteria also eliminate the clinician struggle over patients who didn’t meet the full tender point criteria. Dr. Stanford says that, “we’re probably missing a lot of people because they just aren’t as tender and didn’t have the 11 points. The new criteria will capture these people.” The symptom severity score is viewed as the biggest advantage of the new criteria. “Many of my patients say, ‘I can deal with the pain, but it is the fatigue or the “fibro fog” that is unmanageable,’ ” says Dr. Stanford.

The revised fibromyalgia criteria are percolating into primary care. Dr. Stanford notes, “At meetings, I always push the new criteria for their friendliness to primary care. You don’t have to do this tender point exam that no one got trained … to do. Look at the numbers from the widespread pain index and symptom severity score; these numbers tell us there is fibromyalgia.” As the fibromyalgia criteria committee intended, Dr. Stanford sees the 2010 criteria as exactly the tool primary care needs to manage fibromyalgia. “Once the ACR 2010 fibromyalgia criteria become known to most physicians, it will be a very good tool. It’s exactly what primary care was looking for when it comes to diagnosing fibromyalgia.” the rheumatologist

Heather Haley, MS, is a medical writer based in Cincinnati, Ohio.

References

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, FitzCharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:600-610.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160-172.