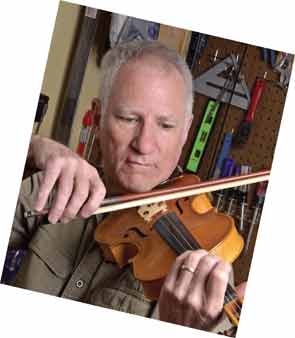

Jay Higgs, MD, has a lofty retirement goal that doesn’t involve medicine, money, or politics: Some day, he hopes to join the prestigious ranks of the best violin makers in the country.

Dr. Higgs, currently a rheumatologist in the Air Force and also director of the rheumatology fellowship program at the San Antonio Military Health System in San Antonio, Texas, learned about violins from his grandfather, who made them as a hobby. Over the past 30 years, Dr. Higgs has hand crafted seven violins. He would enjoy nothing more than to have his instruments played by master violinists and appreciated by generations to come.

From a Chance Find in Medical School

As an adult, he entered the trade almost by accident. Or maybe it was destiny. During medical school, he often studied in the basement of the music library because it was quiet. One day, he started browsing the books in the stacks and discovered one about making violins. He read it from cover to cover, knowing that he would soon follow in his grandfather’s footsteps.He started making his first violin during his fellowship in the mid-1980s. He used the handmade tools he inherited from his grandfather and applied the woodworking skills he developed in his spare time as a cabinet maker. He finished the violin nearly two years later, after moving to San Antonio.

“I found it really relaxing and something that took me away from everything else in the world,” he says, explaining that this hobby combines craftsmanship, art, history, and even the science of acoustics. “I just enjoy every aspect of it.”

He also plays the violin, although not very well, by his own admission. Still, he doesn’t let that discourage him. When his son and daughter were growing up, he made fractional-sized instruments for them, passing along his love of violins and violin music. His son has almost completed building his first violin, making him a third-generation violin maker.

Years ago, his musical family served as the orchestra for their church. He and his children played the violin while his wife played the flute. More recently, Dr. Higgs also performed at several weddings.

Despite his musical ability, he would rather make violins than play them.

“Every violin maker has a dream of making the best sounding instrument,” says Dr. Higgs. “My dream would be to enter the Violin Society of America’s (VSA) competition, which they have every two years, and at least win a sound award.”

He explains that VSA hands out two types of awards—one for sound and another for craftsmanship. When a violin earns high enough marks in both categories, it earns a coveted gold medal.

But that accomplishment will have to wait until he retires in another five to 10 years. At that point, he plans on devoting much of his time to building “really high-quality instruments,” then experimenting with ways to enhance the sound.

Dr. Higgs spends between 100 and 150 hours making just one violin. Due to his hectic schedule, he finishes one instrument almost every two years.

How’s Your Purfling?

The violin hasn’t changed much since it was introduced in the 16th century, he says. Antonio Stradivari—who’s still the world’s most well-known violin maker, even after his death nearly 300 years ago—changed the length a few millimeters, but everything else basically remained the same.

Dr. Higgs spends between 100 and 150 hours making just one violin. Due to his hectic schedule, he finishes one instrument almost every two years. After making violins first in his basement then in his garage, where summer temperatures typically soar to nearly 100 degrees, he built an air-conditioned workshop adjacent to his garage. “It’s a very comfortable place to work,” he says.

While it doesn’t take much to make a violin sound bad, he says it requires a lot of expertise to make one sound good. Just one mistake during any part of the construction process can negatively impact the sound quality.

The process starts with purchasing basic blocks of wood from specialty distributors. He says the violin’s complex curves are carved to shape with only the sides being bent with hot steam. The back and sides are made from hard, sturdy maple.

There are many other steps, such as carving the scroll, which is a very complicated set of curls. But he says the most difficult challenge is inlaying the purfling, which are the two black lines running down the front and back of the violin. It’s actually three layers of wood—an inlay composed of two black and a white middle layer.

“A violin maker always looks at another violin maker’s purfling,” he says. “That’s the ultimate test of craftsmanship.”

Dr. Higgs recalls his first attempt at making a purfling. He threw it away, then retrieved it out of the garbage the following day. He worked on it until it appeared “reasonable,” he says, adding that an experienced violin maker would call it “amateurish.”

Still, there are other aspects to appreciate, like the scroll. But the instrument’s real beauty is its sound. He says every violin maker considers this same question: Does it require effort to make sound or does the violin seem to sing naturally by itself?

With more than 200 violin makers in this country, many of whom are outstanding, he says there is plenty of competition.

“I’m not sure I’ll ever match their quality,” he says. “That’s the thing about violin making. You can always do better. There’s always room for improvement. You never quite reach your ultimate goal.”

Carol Patton is writing the Rheum After 5 series for The Rheumatologist.

New Department Looks Beyond Rheumatology

The Rheumatologist’s new department, Rheum After 5, highlights interesting and unique hobbies that rheumatologists and health professionals pursue after the workday is over. If you know someone who should be featured in Rheum After 5, send your suggestion to the editor.