Elliot Rosenstein, MD, spends most weekend mornings and late afternoons a bit differently than other rheumatologists. He feeds and waters chickens, rabbits, llamas, horses, goats and guinea fowl, as well as an orphaned peacock.

Dr. Rosenstein is one of two medical directors at the Institute of Rheumatic & Autoimmune Disease (IRAD) at Overlook Medical Center, Summit, N.J. In his personal life, he’s something of a gentleman farmer. He lives on a 10-acre farm (formerly a horse farm) in Far Hills, N.J., roughly an hour west of New York City, that he purchased with his wife Laura Kushner, DDS, a periodontist, nearly 30 years ago.

“My wife has been the one tending the farm on weekdays,” says Dr. Rosenstein. “I consider myself weekend hired help.”

The couple and the three children they raised on the farm consider these animals their extended family despite their unusual habits and personalities. They don’t mind that Minx and Lexi, both llamas, occasionally spit at each other—and on humans.

Background

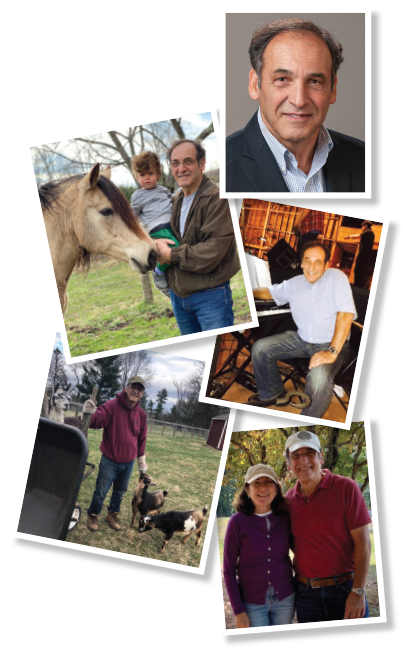

Images from top to bottom: Dr. Rosenstein; Dr. Rosenstein with his grandson, Paxton, and Gaela, the family’s horse; A few years ago, Dr. Rosenstein returned to the Priscilla Beach Theatre, Plymouth, Mass., where he had worked in summer stock in the 1970s; Joey the llama, Dr. Rosenstein, Cocoa and Chip, the Nigerian dwarf goats; Dr. Rosenstein and his wife, Laura Kushner, DDS, on their family farm.

In 1978, Dr. Rosenstein graduated from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (now The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), New York. He spent the next four years completing his residency and chief residency in internal medicine at New York University (NYU). He stayed on for an additional two years to complete a fellowship in rheumatology and to conduct research on the mechanisms of inflammation.

Since then, Dr. Rosenstein has held a variety of positions, ranging from faculty member and rheumatologist in private practice to pharmaceutical industry consultant. He now serves on the faculty at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and is also a professor of medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

Years ago, he and his wife proposed the connection between the organism, Porphyromonas gingivalis, which causes periodontal disease, with the development of rheumatoid arthritis. And he’s one of a few rheumatologists with a dental school appointment. Since 2009, he has served as an adjunct professor at the Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, Newark, N.J.

Dr. Rosenstein also combined his efforts with Neil Kramer, MD, a director and rheumatologist at IRAD, to build an academic Division of Rheumatology at the institute. It supports 18 rheumatologists who deliver quality care, perform clinical research and teach the next generation of rheumatologists.

From Buying Hay to Mending Fences

When Dr. Rosenstein and his family moved to the farm, they wanted to make good use of its 10 acres. A neighbor suggested they purchase steers, which are generally low-maintenance animals. That first year, four steers lived on their farm. At the end of the season, his three young children were horrified when they learned the fate of their pet cows; they were to be auctioned off to a slaughterhouse. One daughter vowed to become a vegetarian and veterinarian (which she did).

From that point on, Dr. Rosenstein and his wife chose non-meat-source animals, such as horses and llamas, to live on their farm.

Farm work is demanding. “I’ve had to learn to do minor carpentry, plumbing and electric work myself,” says Dr. Rosenstein. “I’m just a rheumatologist, not a neurosurgeon. I can’t afford to constantly hire professionals, so we’ve had to do much of the work ourselves.”

He describes mending fences, cleaning stalls, acquiring hay and, even, delivering medical care on occasion in lieu of veterinary visits and their ensuing expense.

Dr. Rosenstein says discussing his farm life often acts as an icebreaker with patients and has taught him a few surprising things as an immunologist.

“Llamas are in the camelid family and have unique antibodies,” he says. “These single-domain antibodies, called nanobodies, can penetrate into tissues more so than human antibodies. Pharmaceutical companies have developed nanobodies for treating COVID-19 and other conditions. That has been an eye-opener for me.”

He says dealing with animals’ social and emotional needs has also been enlightening. One llama, Hank, recently died of a suspected cardiac condition. Hank’s brother, Joey, exhibited a sudden personality change following Hank’s death. He actually appeared to be grieving, says Dr. Rosenstein.

“I’ve been intimately involved in the emotional lives of these animals,” he says, adding that he and his wife purchased two dwarf goats to help Joey deal with his loss.

A Star Is Almost Born

Dr. Rosenstein’s other love—behind animals—is musical theater. He started taking piano lessons at age 7 and performed at recitals. Later on, he accompanied singers, which led to experiences in musical theater. After spending some time performing on stage in high school and college, “I came to the realization that I wasn’t a very good actor or singer,” he says. So he returned to his roots as a musician, learned the art of conducting and became the student conductor of the musical theater organization while attending Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

“That led me to conducting the orchestra in summer stock for two years in Plymouth, Mass., during medical school,” he adds. “I was also the on-stage pianist for a single performance of an ill-fated, off-Broadway musical production, “Can You Smell Gas?” That musical lived up to its name, closing after only one weekend.

Occasionally, he returned to the theater to play piano in the pit orchestra for his children’s high school productions. Now he coaches singers during the summer at the same summer stock theater.

He says learning to be a conductor taught him how to deal with large groups of people, which proved valuable when he became a chief resident at Bellevue Hospital, New York. He says it helped him bring different groups of people together to “play in harmony.”

Joyful Experience

Dr. Rosenstein says living on a farm has been challenging, but it has also “been physically and intellectually rewarding. It’s my gym membership and my grandchildren’s personal petting zoo. It has been a wonderful experience and [an opportunity] for my family to learn responsibility, compassion for others and respect for nature.”

Carol Patton, a freelance writer based in Las Vegas, writes the Rheum After 5 column for The Rheumatologist.