Paul Rochmis, MD, now a retired rheumatologist in Vienna, Va., had never ridden a motorcycle in his life. But back in 1964, when he moved to London for six months—he earned a research fellowship at Westminster Hospital Medical School—he needed inexpensive transportation.

The only problem was first-time motorcyclists who were British could only purchase small and underpowered 250cc motorcycles. They also were issued a red license plate that featured a capital letter L, which stood for learner.

“It was embarrassing,” recalls Dr. Rochmis. “It was like having a scarlet letter.”

But Dr. Rochmis was American and held an international driver’s license. The same rule didn’t necessarily apply—or so he hoped. Since he wanted a larger, 350cc Norton Navigator, Dr. Rochmis had no intention of admitting his novice status. So when the salesman at the dealership asked him if he had ever ridden a motorcycle, Dr. Rochmis relied, “of course,” then added, “But I’m only familiar with American motorcycles. Why don’t you show me how British bikes work?”

After a five-minute crash course, Dr. Rochmis intended to quickly drive away before the salesmen realized that he had no riding experience and brand him with the red license plate. But not everything went as planned.

“I popped it into a gear, hoping it was first, but it was third gear,” he says, adding that although he chugged away, practically stalling every few feet, the salesman never stopped him because he wanted to dump the motorcycle, which Dr. Rochmis later discovered was an inferior model. It took Dr. Rochmis 90 minutes to drive home in rush-hour traffic, a trip that would normally have taken less than an hour. But by the time he arrived home, Dr. Rochmis says he was an experienced rider.

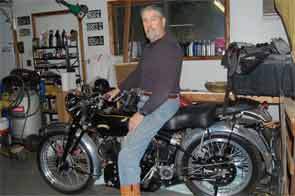

Since then, no one would ever dream of giving Dr. Rochmis a red license plate. Besides riding motorcycles, he also collects them, having purchased roughly 30 bikes over the last several decades. However, they’re not just any bikes. Many are Vincents and Velocettes, high-end British bikes that would make most devoted bikers drool. To him, such motorcycles are objects of beauty. While Dr. Rochmis still owns nine motorcycles, he’s not done shopping. He may never be.

Together Again

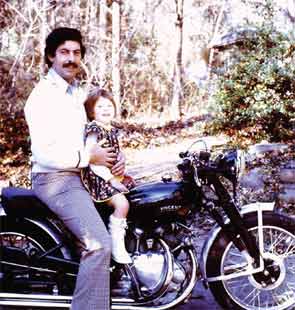

In 1964, during his internship, he met his future wife, then a fourth-year medical student. When they married, he says they were living hand-to-mouth and needed a bed. So Dr. Rochmis made the ultimate sacrifice. He sold his motorcycle and didn’t ride or purchase another bike until 1972, due to life’s typical distractions like family and career.

His second purchase was a Yamaha endure bike, an on- and off-road bike. Yet he couldn’t shake the image of a bike he had seen years ago.

“When I was around 15 or 16 years old, thumbing through a bike magazine, I saw a picture of a Vincent Black Shadow and thought this was the most beautiful motorcycle I had ever seen,” he says. “It’s an icon of motorcycles.”

Over the years, he ended up purchasing five Vincents but sold three. Then he explored other brands like Velocette and Triumph. He’s currently negotiating to purchase another Velocette. “I have none now,” he says. “I feel I need one for my soul.”

Although his BSA Gold Star won the “Best Special” motorcycle national award roughly 20 years ago, he’s never entered his cherished collectibles in any other competitions. He doesn’t feel the need to “shine up his bike,” he says, or brag that his bike is better than most others. He simply enjoys them, and that’s good enough for him.

He prefers older motorcycles because they have “mechanical honesty.” Although he owns a red 1989 Honda GT 650, he believes those built in the 1950s or 1960s that are all black with a little chrome and accented with gold are the most beautiful.

For him, the attraction is visceral.

“Motorcycles appeal to many of the senses,” says Dr. Rochmis, adding that sometimes he performs his own minor repairs. “I like the smell of metal, a little oil, and a whiff of gasoline. It appeals to the ears in terms of the sound of a beautiful running engine. The bike and you sort of come together … a little like the way a horse and horse rider come together.”

That’s why it’s so hard to let go. He says he turned down a very substantial offer for his Vincent Black Shadow less than two years ago.

As a member of the Vincent H.R.D. Owner’s Club, an international organization, Dr. Rochmis has made friends with motorcyclists from around the world. Years ago, he attended one club meeting in Canada, bringing champagne for its 100 members to toast their good fortune as Vincent owners. They nicknamed him Champagne Paul, which has stuck through the years.

Last year, he and his wife traveled to New Zealand. During their one-month vacation, they stayed with four different club members.

“They didn’t know us,” he says. “But because we’re part of the Vincent Owner’s Club, we were part of the Vincent family.”

Likewise, one of the world’s greatest motorcycle engineers—Phil Irving, now deceased—stayed at Dr. Rochmis’ house when visiting from Australia. Dr. Rochmis says Irving contributed to the design of both Vincents and Velocettes back in the 1950s.

Now that Dr. Rochmis is mobile after two knee replacements, he’s ready to ride again. And maybe do a little shopping. The lure of metal, chrome, oil, and gas are simply irresistible.

Carol Patton is writing the “After 5” series for The Rheumatologist.