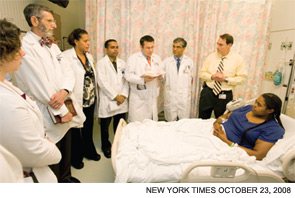

Let my former faculty, residents, and patients briefly tell of this work in their words. You don’t always need statistics to know if you’ve affected a patient or truly touched a student or resident or colleague, to realize that an attitude and approach has changed, or to appreciate the sparkle in an eye or expression on a face. When I first told my faculty (Drs. Ashish Parikh, Sunil Sapru, Anthony Carlino, and Mindy Houng) and collaborators Dr. Paul Wangenheim and M. Martha Eide that I wanted to bring humanities to daily hospital rounds, their response was shock and disbelief. After much dialogue, education, and preparation over many months, and after initial experiences on rounds, “We slowly became believers. This became a route to learning that discussion of hypertension just doesn’t reveal. When a patient is included, it’s a particularly powerful experience, for we see them as more than the sum of their abnormal labs and radiographs. Moreover, our patients have a chance to see that we, too, are human beings.”

All were affected. “The residents and students truly enjoy our daily humanities rounds. Their journal entries reflect their personal growth, insight into human nature, and special connections with patients. There’s a tangible and measurable effect on the residents.” We came to embrace the humanities. “They keep us focused on the reason we all went into medicine in the first place—to care for that person we refer to as ‘the patient.’ We think more these days about what we do for our patients and how it affects their lives. We take more time to ask about and reflect on the unique journey of each patient. We are all better for this.”

Residents changed, too. One of my senior residents at the time, Frantz Pierre-Louis, MD, eloquently expressed the sentiments of his peers. He and his peers initially had reservations. However, he says, “as time passed, my uneasiness settled. Bedside humanities were not a burden but a precious asset that would benefit not just my career but my life in its entirety.” Indeed, he notes, “there were times when we would discuss, animatedly, issues that seemed to have nothing to do with medicine. I saw more passion in those exchanges than during traditional discussions of coronary disease.”