COMING ATTRACTIONS

I came across a couple of reports that have the potential to profoundly change our thinking and practice (if the work is confirmed, extended, and found applicable to human disease). They are worth noting.

The first (J Exp Med. 2010; 207: 1067-1080) addressed immunologic control of memory, something with which I was unfamiliar. Apparently, certain cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–a, interleukin (IL)-1 b, IL-6, and IL-12) have a detrimental effect on cognitive function. Also, innate—and perhaps adaptive—immune mechanisms mediate numerous central nervous system functions in normal and Alzheimer-affected brains of experimental animals. The elegant studies documented a substantial contribution of IL-4–producing T cells to cognition. It occurred in the choroid plexus (Remember those old studies of the choroidal immune response in systemic lupus erythematosus done, incidentally, at my new institution, the University of Southern California, by one of my new colleagues, Frank Quismorio and his collaborators?), ventricular margins, and subarachnoid spaces. This may represent a paradigm shift in understanding immunologic events affecting memory and developing novel approaches for immune-based therapies for cognitive impairment.

The other report (Nat Med. 2010;16:592-598) was about resolvins for pain. Resolvins (whose name signifies “resolution phase interaction products”) are derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids. They act in nanomolar and picomolar doses. In standardized animal models they attenuate pain caused by tissue injury, nerve injury, and capsaicin injection. Pain reduction in animals was moderate, so it remains to be demonstrated that resolvins will be effective in clinical medicine. But there seems to be excitement about the possibility that these natural products, which may not have the adverse effect profiles of opioids or COX inhibitors, are certainly good candidates for trials in human pain syndromes.

Maybe soon I’ll be taking resolvins for my running injuries along with an IL-4 pill, a statin, chocolate, and wine. I certainly hope I’ll be prescribing resolvins for patients with chronic back pain and fibromyalgia.

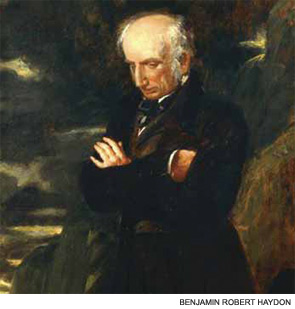

THE CHILD IS FATHER OF THE MAN

That is Wordsworth, for those who may have forgotten.

I was very pleased to see a nice presentation of 10 cases and a review of the world literature (84 cases) of Kawasaki disease (KD) in adults (Medicine. 2010;89:149-158), which began to be recognized around 2005.

I’m pretty sure I’ve seen this condition in adults before it was accepted as a possibility. I recall commenting on rounds some years back that I would have offered this diagnosis if it occurred in adults—and now it does. Some patients fulfill diagnostic guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for children. Others are said to have “incomplete” KD (analogous to “incomplete” lupus) when they have typical coronary arterial involvement accompanied by fever and features of severe inflammation without other explanations for the illness.

Thinking about this evokes several memories. The pediatric immunologist who has been one of the leading authorities on KD, Stan Shulman, and I shared lab space when I began my academic career at the University of Florida a long time ago; we and our families became good friends. I’m proud of and happy for Stan’s distinguished career. My failure to definitively diagnose adult KD reminds me, too, of similar prior experiences. My lab identified important effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on in vitro and in vivo mononuclear cell function when I was a young investigator, and I wasn’t experienced enough then to confidently extrapolate the observations to perturbations of prostaglandin-mediated effects. We also described silicone-related rheumatologic syndromes, in error in retrospect, as did others. We also reported “Rheumatic syndromes presenting with ischemic vasculopathy of the extremities” (Clin Res. 1981;29: 851A), not recognizing these patients as having the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, described years later, that they undoubtedly did. My mom would have loved a “Panush’s syndrome”; she was disappointed each year they announced the Nobel prizes and my name was never among the awardees.

Dr. Panush is professor of medicine, division of rheumatology, department of medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California in Los Angeles.