A Musical Interlude

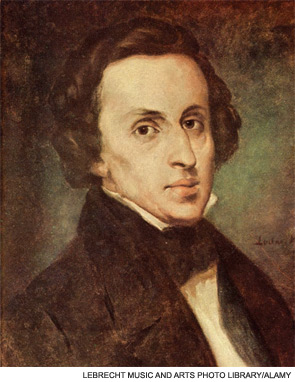

There was a piece in the literature recently about the illness of the musician Frederic Chopin.1 A favorite interest of mine has been rheumatology (and medicine) in history, literature, art, music, and biblical lore. I find it fascinating to try and understand how illness affected great artists, leaders, and history. Some examples include:

- Saturnine gout causing the fall of the Roman Empire;

- Sir William Pitt the elder’s gout forcing him to miss the parliamentary debate that enacted the tea tax and led to the colonies’ rebellion and the American revolution;

- Tsaravich Alexis’ hemophiliac arthropathy precipitating Tsarina Alexandra’s invitation to Rasputin to help (mis)govern and the resultant fall of Imperial Russia leading to nearly a century of communist rule;

- King George III’s porphyria and its subsequent implications for the colonies and Irish rule;

- Napoleon’s loss of the fateful battle of Waterloo because of a hemorrhoid;

- Renoir’s magnificent creations despite his crippling rheumatoid arthritis (RA);

- The evident effect of his scleroderma on Klee’s painting; and

- The historical and religious consequences of King Saul’s pituitary tumor (some references can be found in Panush and Caldwell; for others, ask me).2

I enjoyed reading about Chopin’s illness. The authors note Chopin’s hallucinations and speculate that his neurologic problems included temporal lobe seizures. I must briefly digress to my piano lessons and then return to Chopin. I took piano lessons beginning at about age seven; my parents wouldn’t let me quit until five years later. I hated it at the time. I desperately wanted to be outside playing baseball, basketball, or football with my friends rather than stuck in the house, compelled to take the after-school instruction and then practice as well. My most notable musical accomplishment was, at a prominent recital, to play my entire piece perfectly but an octave too low (for anyone who doesn’t know music, that’s probably equivalent to injecting the wrong joint or operating on the wrong limb). My younger sister was very good, however, and she got to play some terrific music, including Chopin’s polonaise #40 (Military, in A major). That moved me. I thought it was great music; it was played on Polskie Radio during the German invasion of Poland in 1939 to rally and inspire the Polish people (it failed).

Of course, now that I am older, I wish I learned piano better and retained some skill. I occasionally sit down and enjoy playing Massenet’s aragonaise or Mozart’s rondo. I have the music for the polonaise, but it not only eludes my meager skill, it also causes arthritis in my hands from the difficulty of the music.

Chopin’s use of piano to express his thoughts and feelings was virtuosic. He died at age 39 years of a chronic illness. His symptoms included cough, breathlessness, hemoptysis, constitutional symptoms (e.g., fatigue, “failure to thrive”), gastrointestinal symptoms including hematemesis, neurologic symptoms, and arthritis. What’s the diagnosis? Most of us would think of the possibility of one of the systemic rheumatic diseases. The literature indeed includes consideration of Churg-Strauss syndrome, but other of our disorders are conceivable.3 Note, however, that his father had respiratory disease, and his sister died young with similar symptoms. Other diagnostic possibilities include emphysema, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, alpha-1- antitrypsin deficiency, hypo- or dys-gammaglobulinemia, allergic broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis, cystic fibrosis, and mitral stenosis. We don’t know what Chopin had, of course, and never will with certainty, so no diagnostic suggestion can be disputed. But isn’t Frederic Chopin a tribute to the human spirit, to the ability to triumph over adversity (which certainly not all our patients with chronic diseases can do)? We can only admire with awe the wonderful contributions he left us, despite illness, throughout his short life.

Orchestral Harmony, the Immune System, and Rheumatic Disease

When I was very young, we were just learning about the elegant complexity of the immune system, its dysfunction, and how that was important in rheumatic diseases. I recall someone describing its normally balanced intricacies as like orchestral harmony with the T cell as the conductor. One of my colleagues then, Selden Longley at the University of Florida, developed a very imaginative analogy of the immune system to football, with offensive and defensive coordinators, a coach, offensive and defensive players, quarterbacks, substitutes, and reserves that he used for his lectures to students. I’m no longer sure who conducts the immune symphony, but the players must still make music properly.

We don’t know what Chopin had, of course, and never will with certainty, so no diagnostic suggestion can be disputed. But isn’t Frederic Chopin a tribute to the human spirit?

I’m unabashedly delighted to be part of rheumatology at the University of Southern California. I think we have a division of which the football team could be proud. I’m therefore pleased today to include work by one of my new colleagues, Song Guo Zheng, a physician and an associate professor doing important research in our division, in collaboration with David Horwitz, our former division chief, and Zhongmin Liu, an immunologist at Tongji University in China, and others.4